- Accueil

- Base de données

- 22

- USAAF

- 8 June, 1944

8 June, 1944

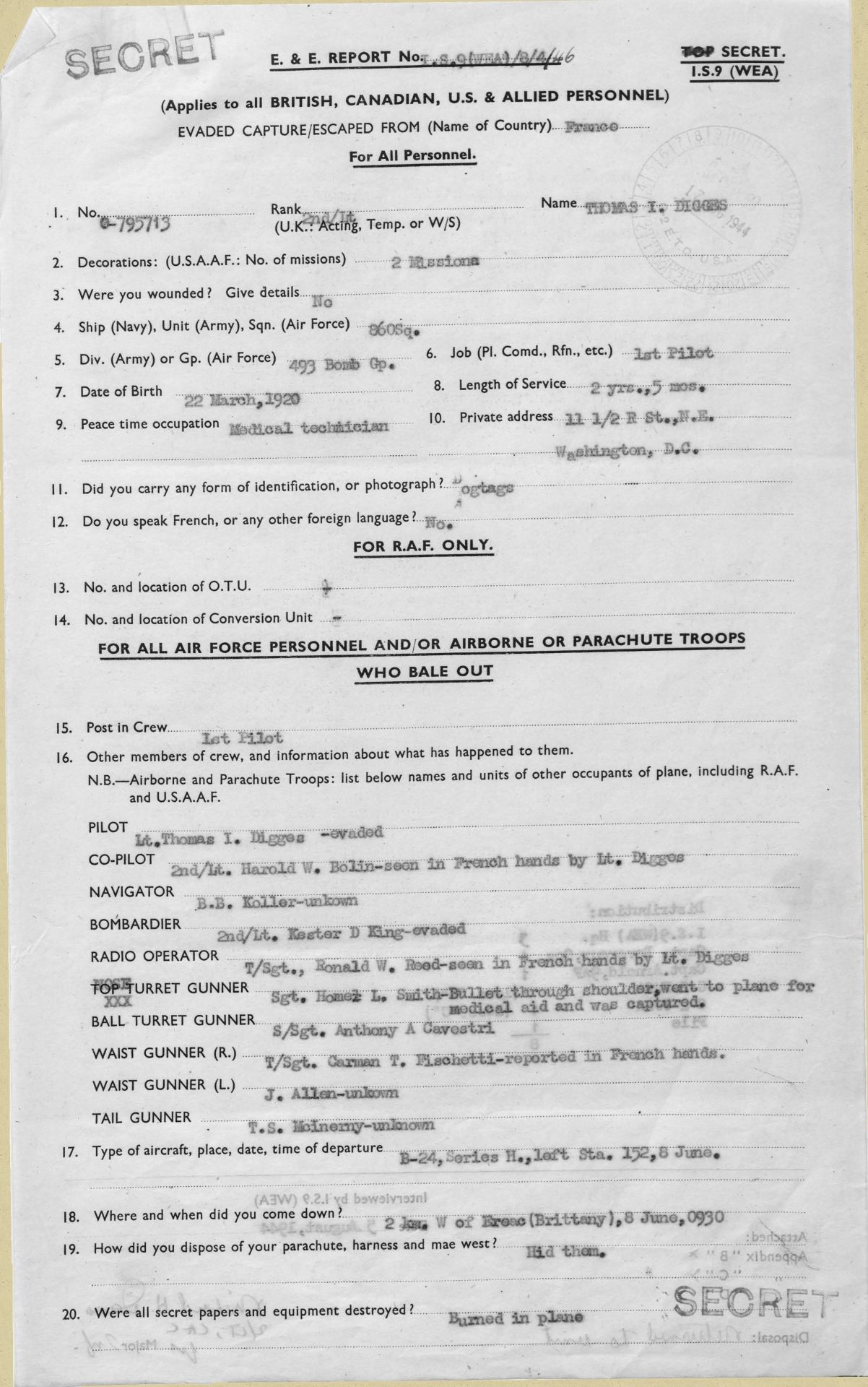

Consolidated B-24H-20-FO (s/n 42-94927 code N6-?)

"La Bodinais", Lanrelas (22)

(contributors : Frédéric Hénoff, Joseph Verger, Noël Pollet, Michel Pieto, Jean-Luc Moser, Jean-Michel Martin, Pierre Mahé, Daniel Dahiot)

"Nose art" of B-24H s/n 42-94927

Photo website "B-24 Best Web"

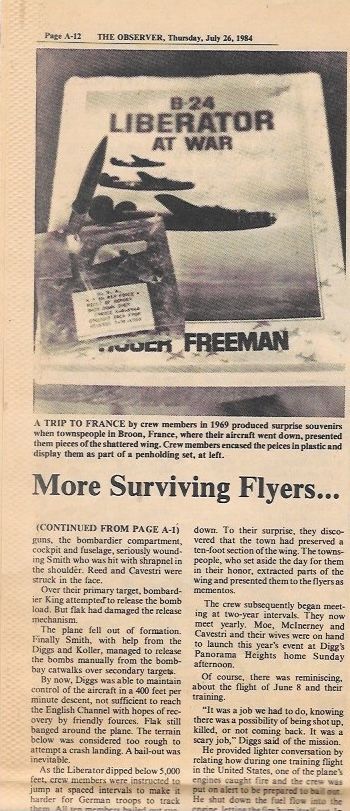

The B-24 fallen in the village of "La Bodinais" in Lanrelas on June 8, 1944 had neither a name nor a drawing painted under the cockpit. Lieutenant Digges and some members of his crew returned to the scene after the war. They confirmed that the plane was for them the ''Shady Lady'' but that this name was not yet painted. Indeed this bomber had just been assigned to them. It was on its second (and last) combat mission. No artist had yet had the time to name it as the crew wished. It is true that the concerns of the moment were other. The name ''Shady Lady'' is found on several aircrafts of the same type including one that crashed on Italian ground, with the simple difference being a different numerical marking. The American Archives recorded the crash of this B-24 registered 42-94927 with also the painted drawing that previously appeared there under the name of "Sweet Job !", on which we can see a woman between "Sweet" and "Job". This is why on this page, we produce this document as we found it.

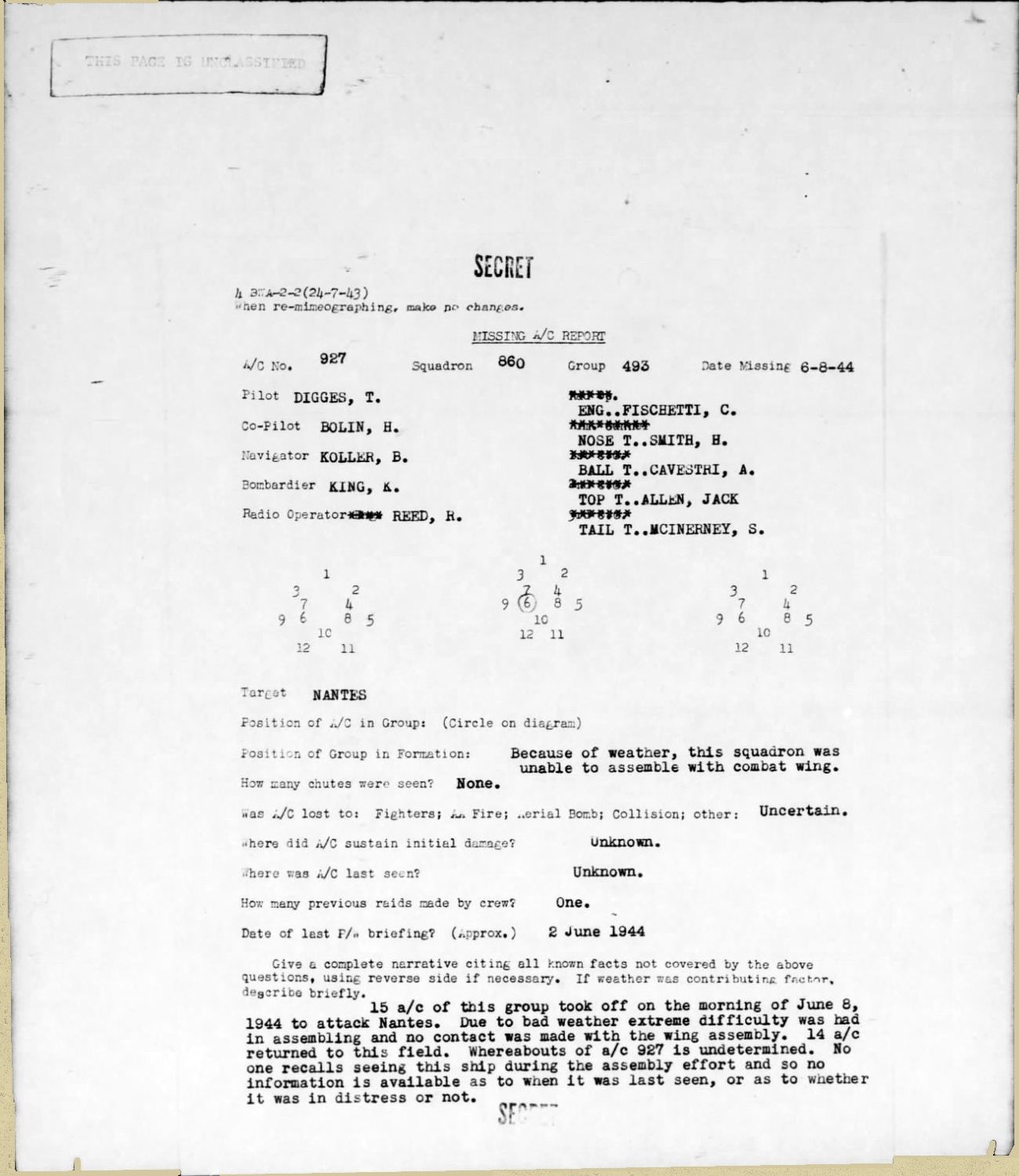

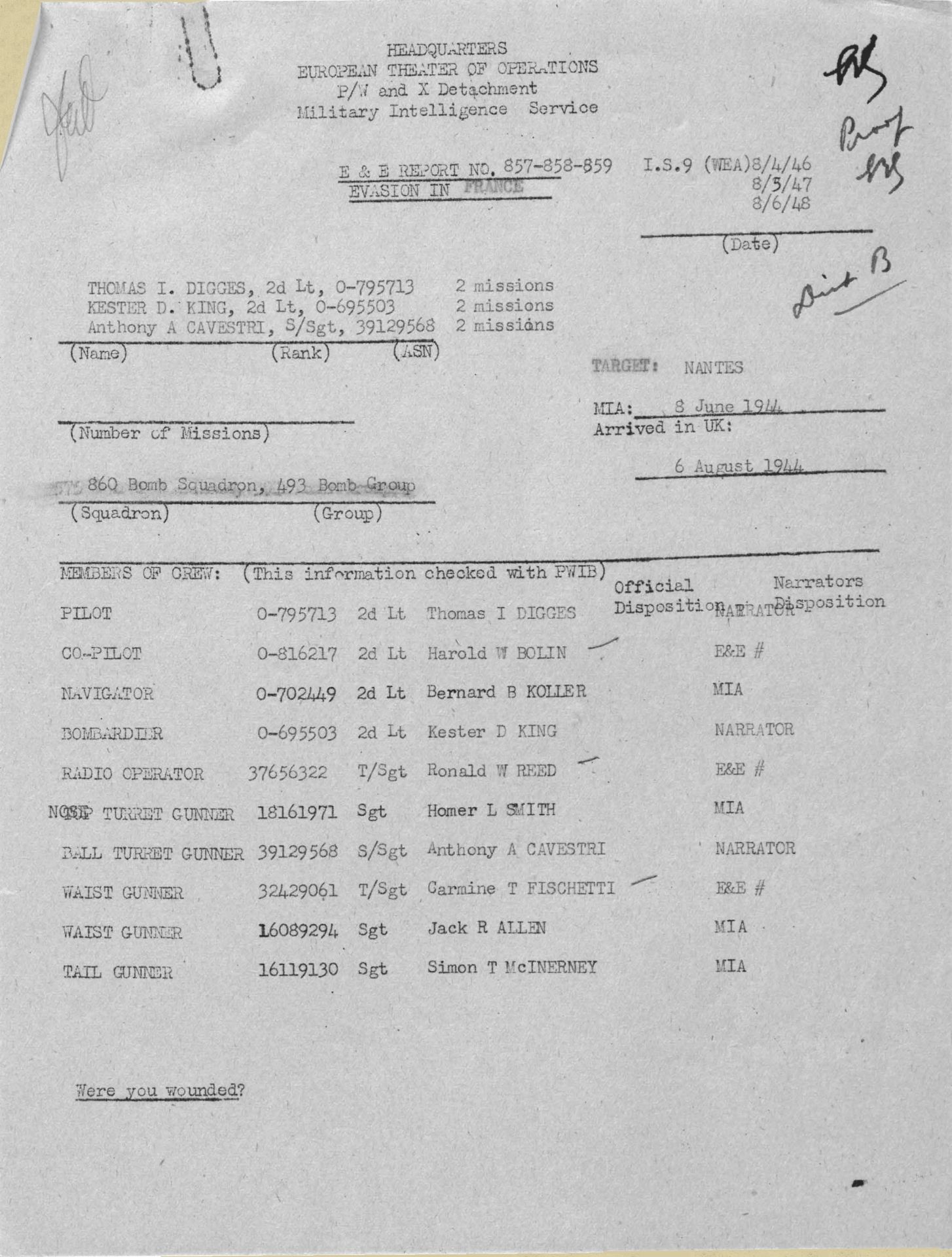

Crew (493rd BG, 860th BS) :

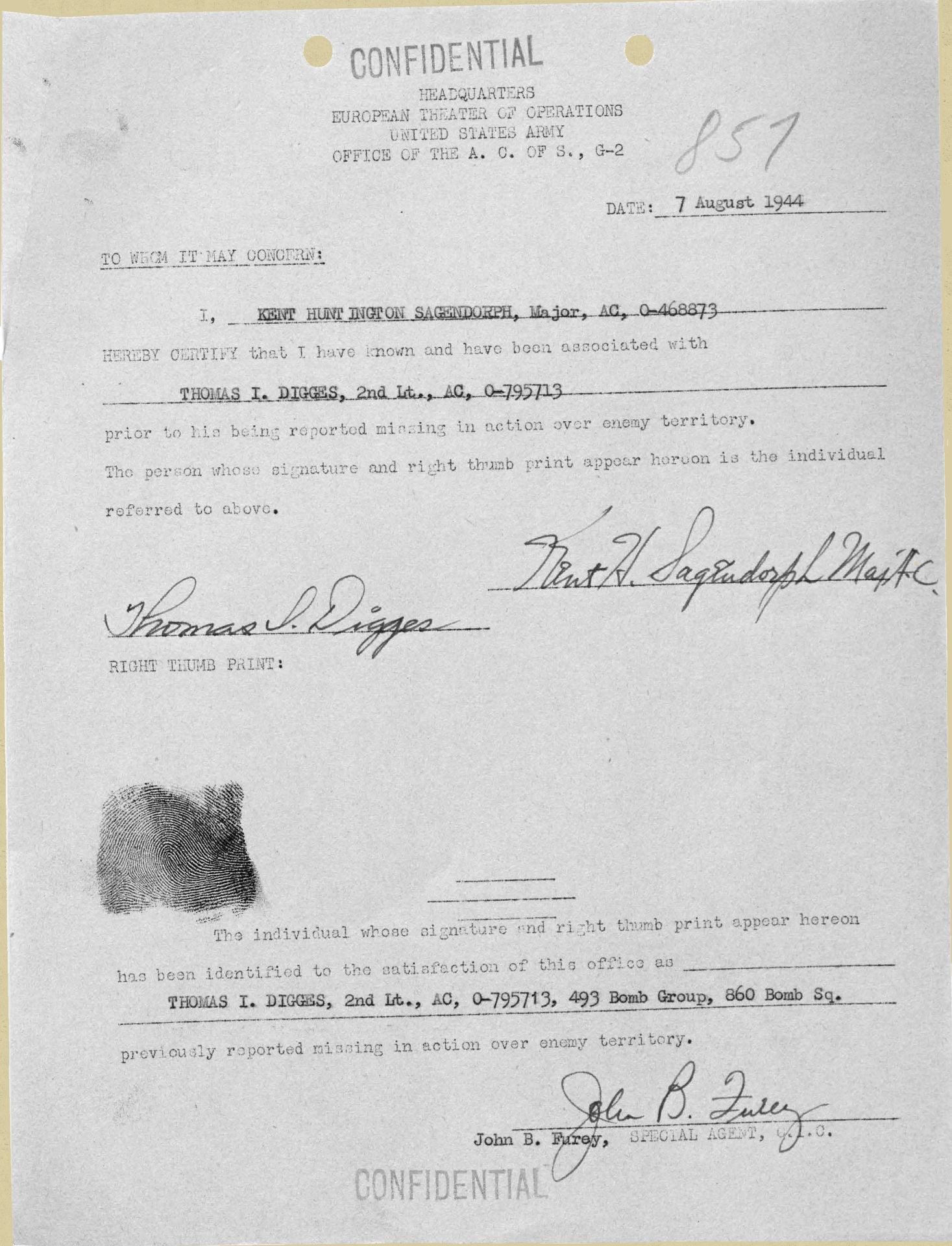

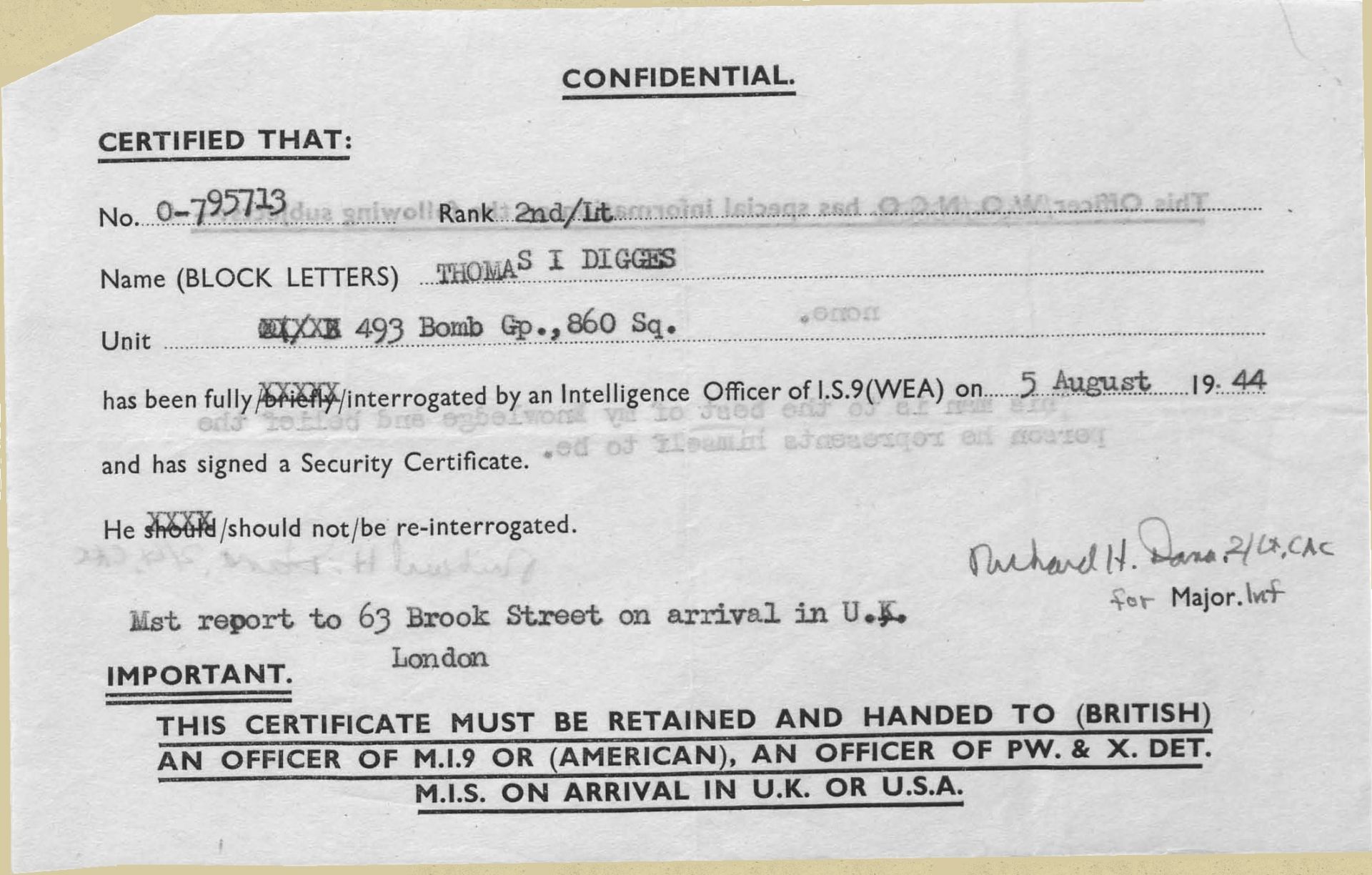

- (Pilot) 2nd Lt. Thomas I. "Tommy" DIGGES (service number O-795713), escaped.

Born March 22, 1920. Enlisted in Washington (District of Columbia).

Joined the Resistance in Charente. Returned to England on August 6, 1944.

Died at the end of 2012, shortly before being made a Knight of the Legion of Honor by President Nicolas Sarkozy.

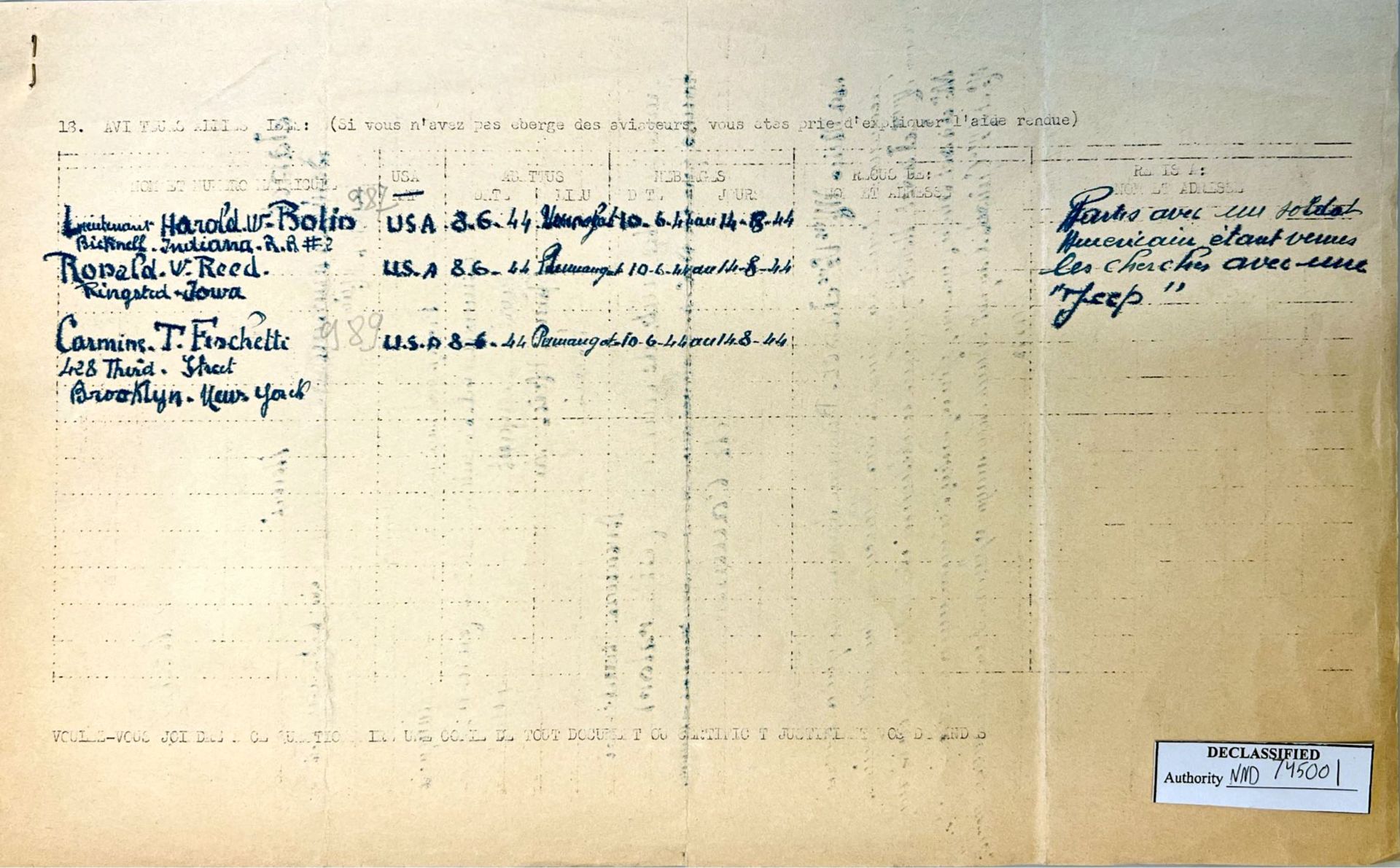

- (Co-Pilot) 2nd Lt. Harold W. BOLIN (service number O-816217), escaped.

Born June 2, 1924 in Bicknell, Indiana, where he resided in 1944. Enlisted in Lafayette, Indiana.

Returned to England on 16 August 1944.

Died on August 25, 2018.

- (Navigator) 2nd Lt. Bernard Burton "Barney" KOLLER (service number O-702449), escaped.

Born December 19, 1920 in Roseburg, Oregon. Enlisted in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Died September 4, 1978.

- (Bombardier) 2nd Lt. Kester D. KING (service number O-695503), escaped.

Born February 23, 1918, in La Porte, Indiana. Enlisted in Chicago, Illinois. Resided in Stark, Indiana.

Died in 1983.

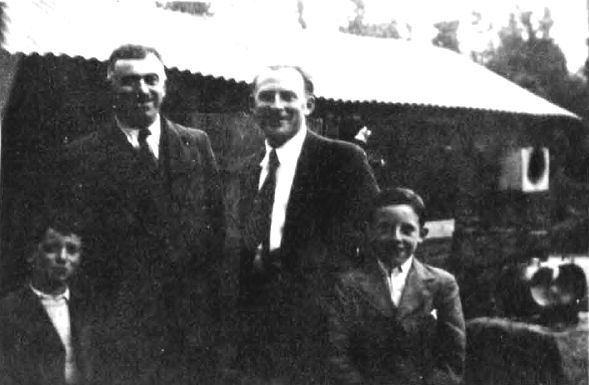

From left to right : 2nd Lt T.I. Digges, 2nd Lt B.B. Koller, 2nd Lt H.W. Bolin, 2nd Lt K.D. King

- (Radio operator) T/Sgt. Ronald Westler REED (service number 37656322), escaped.

Born October 2, 1923 in Ringsted, Iowa, where he resided in 1944. Enlisted at Camp Dodge, Iowa.

Returned to England on 16 August 1944.

Died July 4, 2002

- (Flight engineer) T/Sgt. Carmine Thomas FISCHETTI (service number 32429061), escaped.

Born September 28, 1920 in Brooklyn, New York. Enlisted at Fort Devens, Massachusetts.

Resided at 428 Third Street in Brooklyn, New York

Died on the 1sterAugust 1988.

- (Ball turret gunner) S/Sgt. Anthony Angelo "Tony" CAVESTRI (service number 39129568), escaped.

Born December 29 (or November) 1923 in Pleasanton, California.

Died on November 11, 2013.

- (Front gunner) Sgt. Homer Lee "Smitty" SMITH (service number 18161971), injured and prisoner.

Seriously injured in the shoulder.

Stalag Luft 4, Gross-Tychow (formerly Heydekrug), Pomerania, Prussia

(was moved to Wobbelin Bei Ludwigslust and then to Usedom Bei Savenmunde).

Born March 26, 1923. Enlisted in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Resided in Ottawa County, Oklahoma.

Died on April 15, 1974.

-(Top turret gunner) Sgt. Jack Roger ALLEN (service number 16089294), prisoner then killed.

Born June 11, 1921. Enlisted in Newark (New Jersey). Resided in Passaic (New Jersey).

Killed on June 21, 1944, at the age of 23.

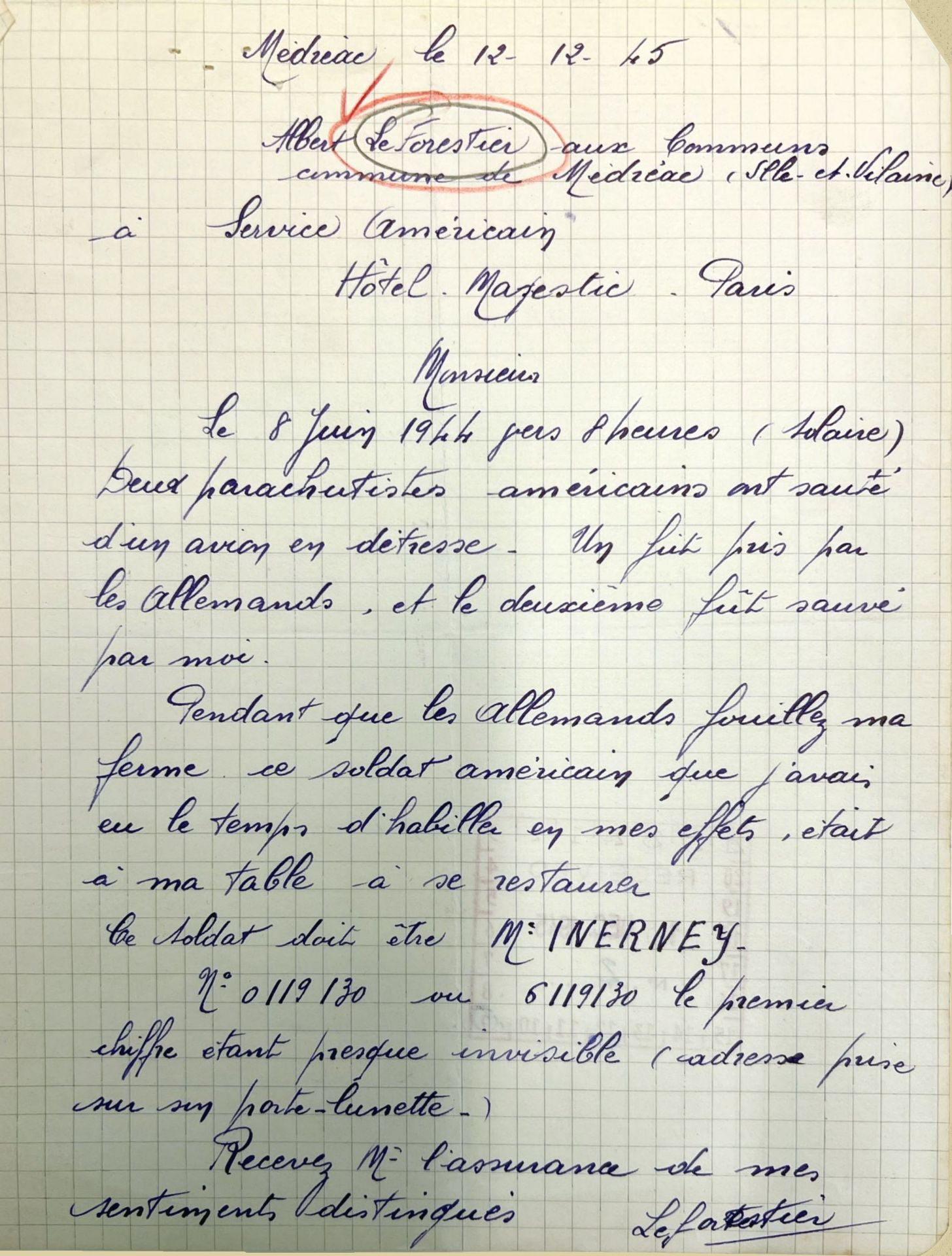

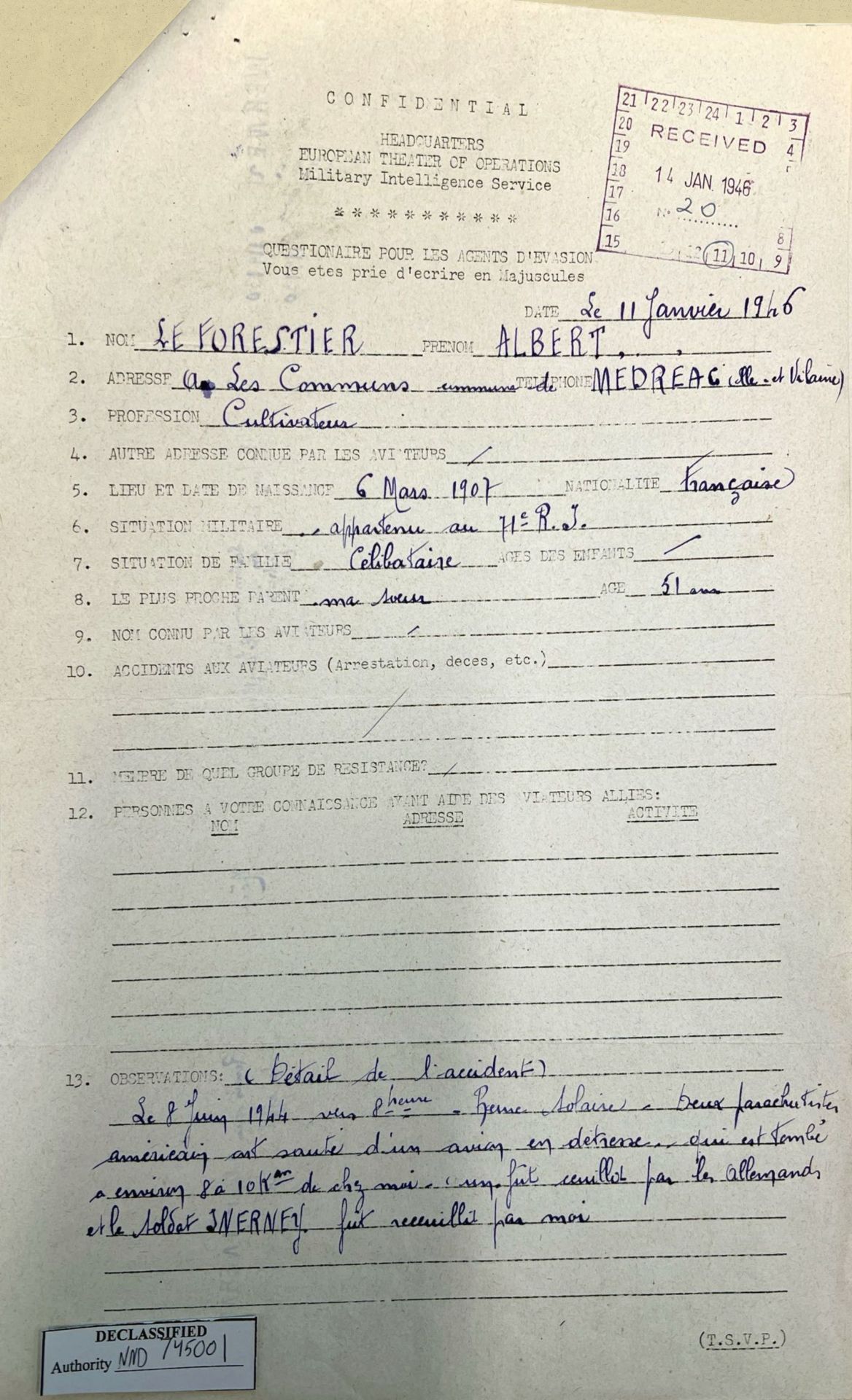

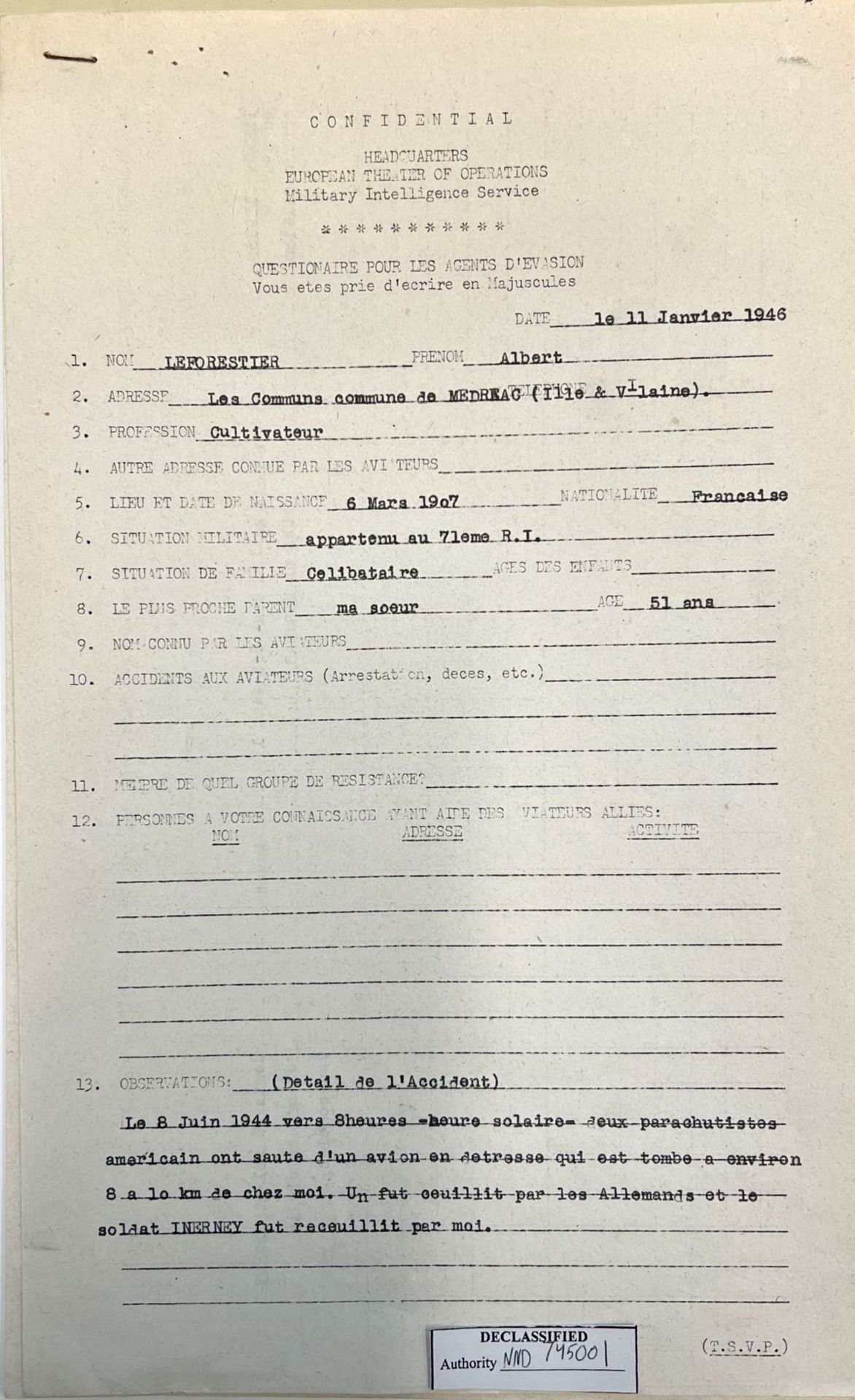

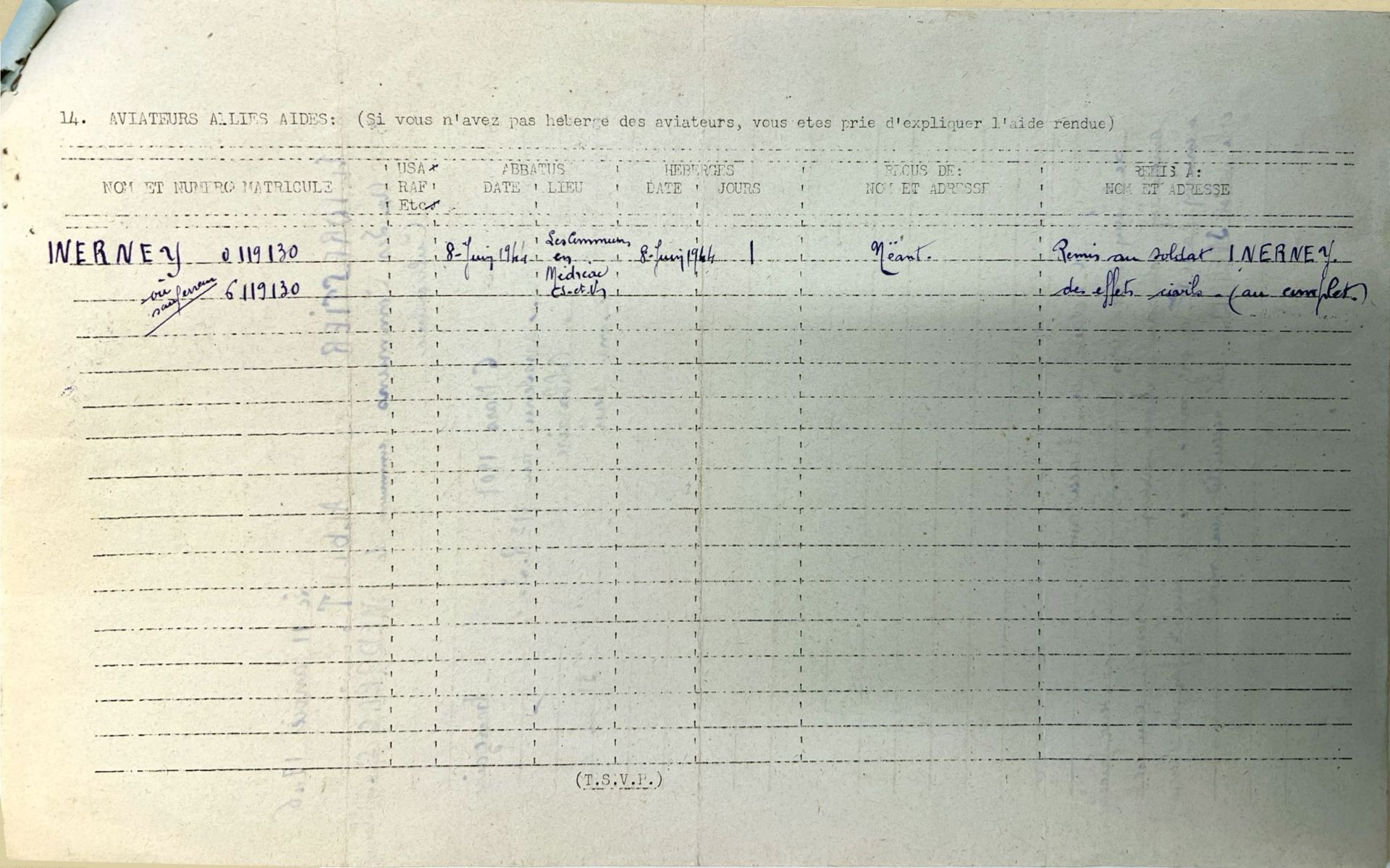

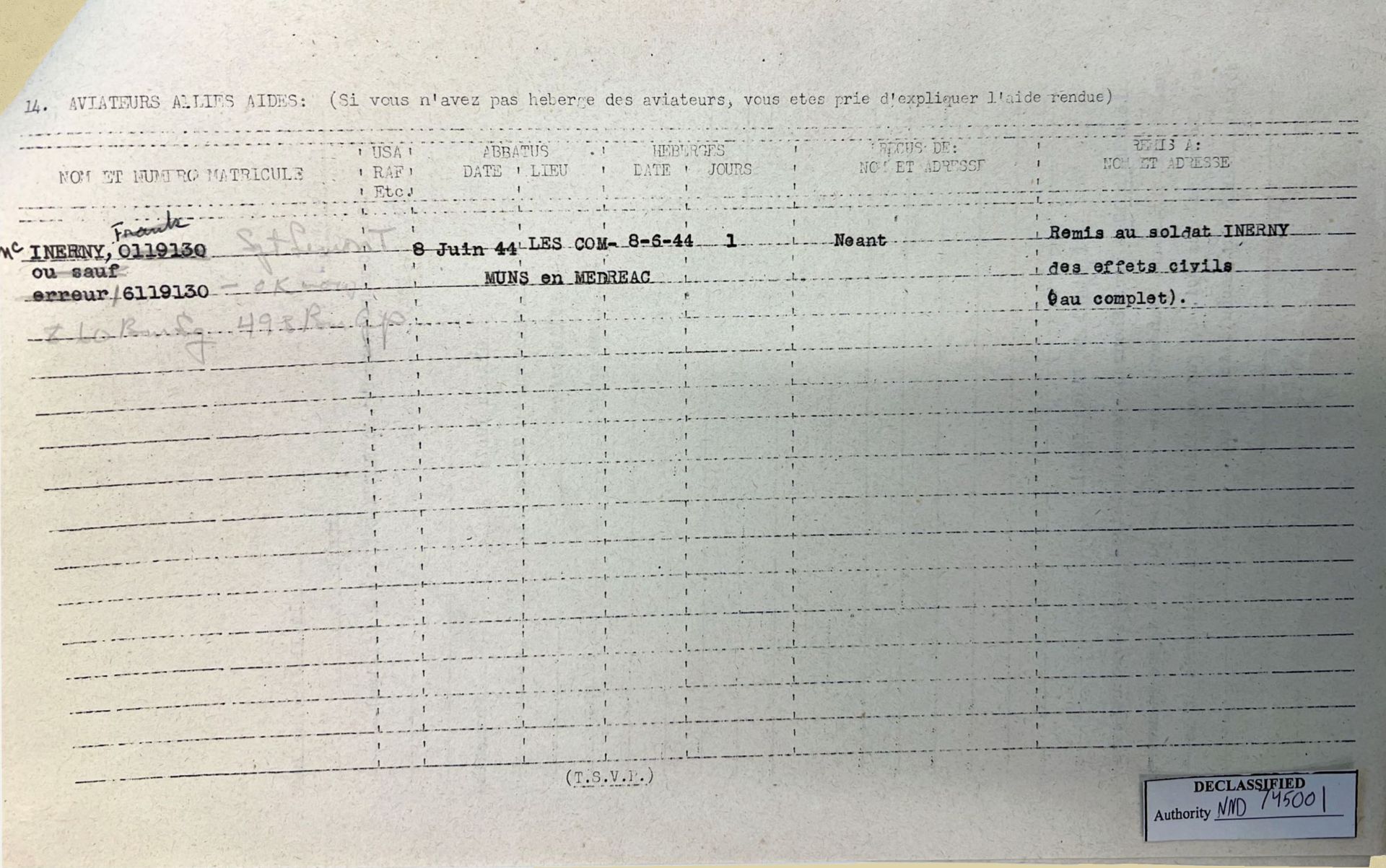

- (Tail gunner) Sgt. Thomas Senan McINERNEY (service number 16119130), escaped then prisoner.

Unknown prison camp. Born September 21, 1921. Enlisted in Jackson, Michigan, where he resided.

Died on April 25, 2012.

Thomas Senan McINERNEY (right)

with his brother “Vin” Martin Vincent McINERNEY,

born in 1917, who made a career

in the American Army.

Photo Deborah Sullivan (nee McInerney)

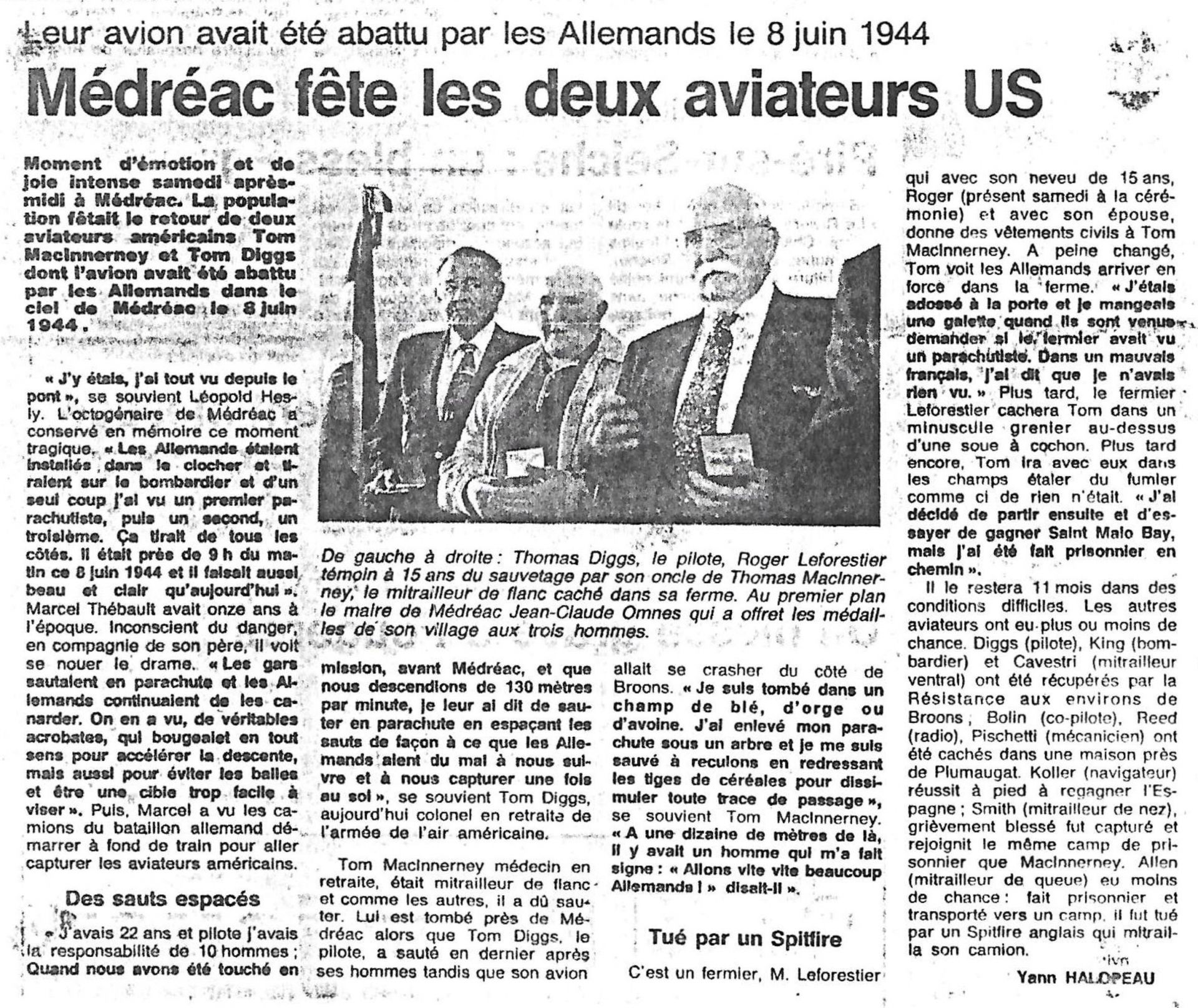

THE STORY

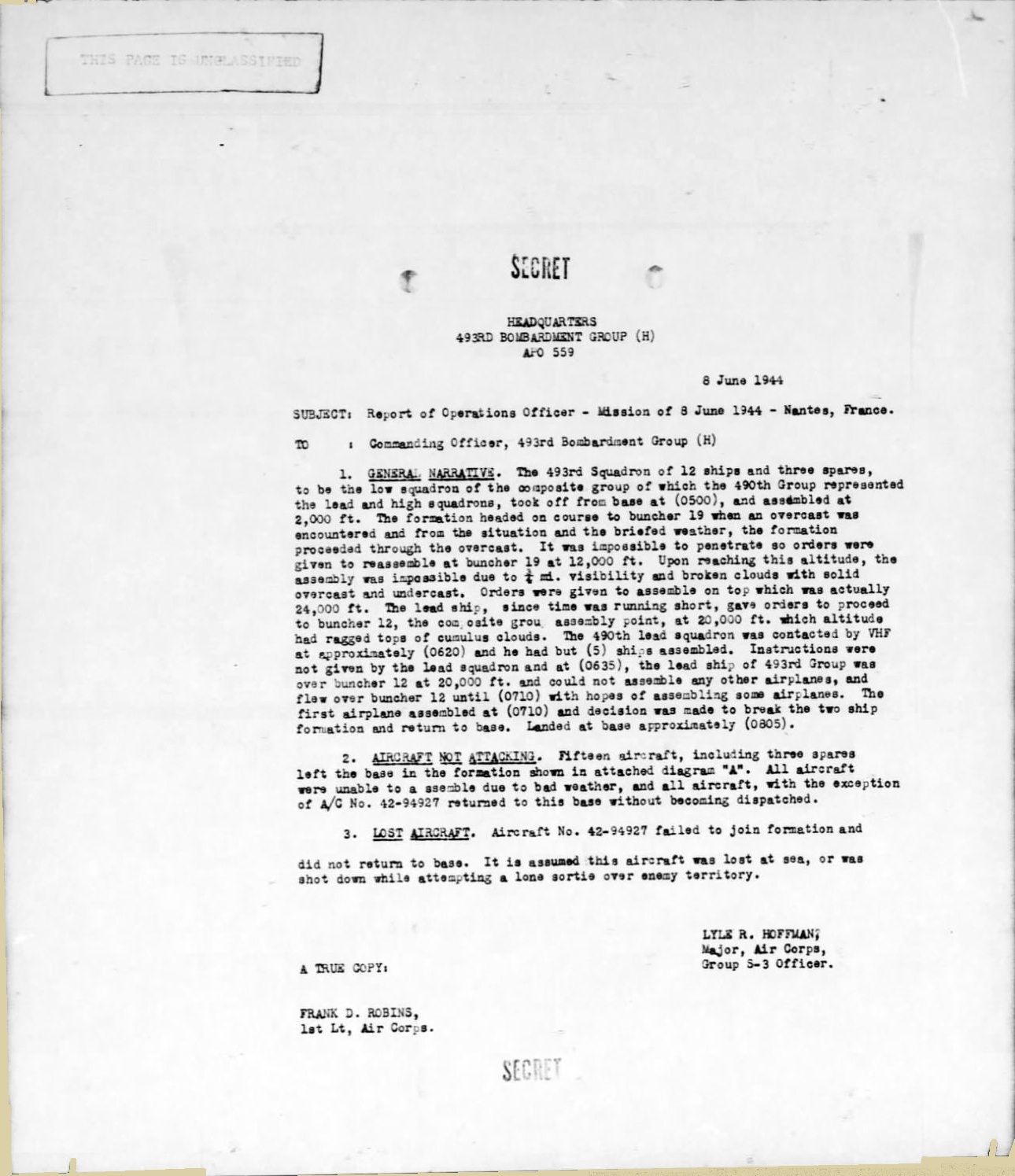

Lanrelas (Côtes du Nord), Thursday June 8, 1944 : crash of a B-24 Liberator in the village of "Bodinais", belonging to the 493th Bomb Group/860th Bomb Squadron (8th USAAF).

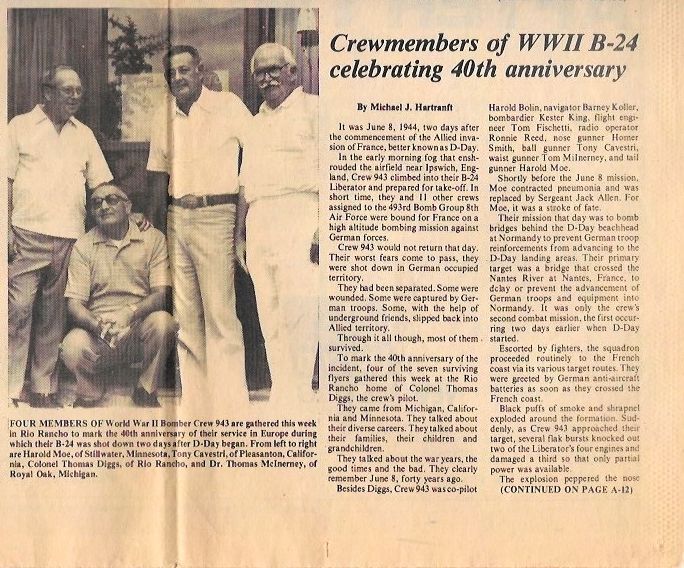

Very early this morning, in heavy fog, at Debach RAF base, near Ipswich, in the County of Suffolk, England (135 km northeast of London), the leaders of crew 943 are summoned by their superiors to a briefing for a bombing mission over occupied French territory. We are on day two of Operation Overlord and the intensity of the fighting is at its peak. It is essential to support the ground forces engaged on Norman territory. This meeting is attended by 2nd Lt Thomas Digges, called ''Tomy'' by his friends, joined by his co-pilot, 2nd Lt Harold W. Bolin. Then, there is the navigator, 2nd Lt Bernard B. Koller, called by his friends ''Barney''. The bomber is 2nd Lt Kester D. King. The radio is Sergeant Ronald W. Reed called ''Ronnie''. These 5 crew members are given the mission to bomb, early this morning of June 8, a main bridge crossing the Loire river near Nantes. It is absolutely necessary to prevent the German forces, stationed to the south of this region, from bringing men and equipment up to the front line which is slowly being established in Normandy. The B-24 of 2nd Lt Digges was to join 14 other bombers from the same unit in flight, which would join other aircrafts taking off from other bases. In total, 42 Consolidated B-24 Liberators and 25 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses would participate in this mission, dropping 94 tons of bombs. The damage would be significant and the mission accomplished. These crew members would be joined by the engineer, Sergeant Carmine T. Fischetti, whom his friends nickname "Tom." The ball turret gunner is Sergeant Anthony A. Cavestry, nicknamed "Tony". The tail gunner is Sergeant Thomas Senan McInerney, also nicknamed "Tom". The front and top turret gunners are respectively Sergeant Homer L. Smith and Jack Roger Allen. All these men received accelerated training during their training in the USA, as the needs of the war were felt.

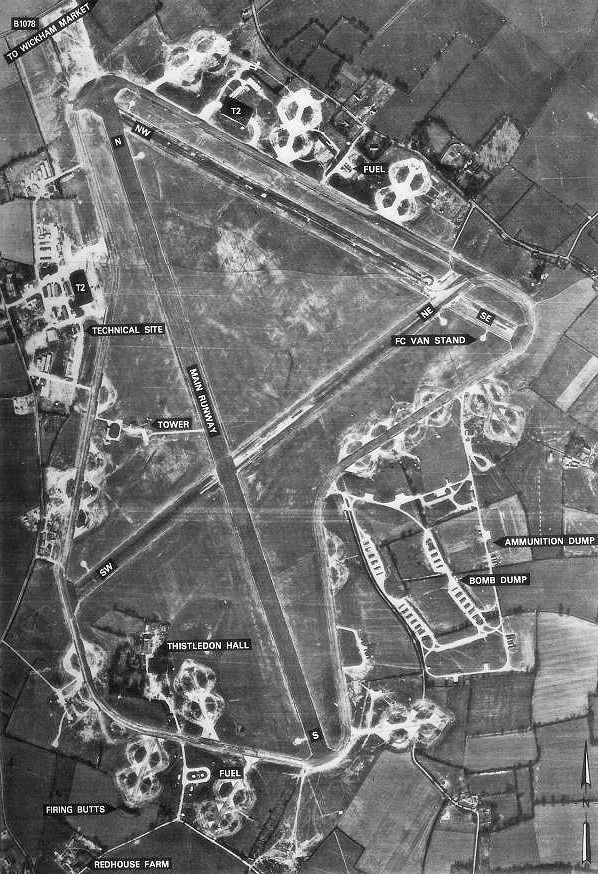

Debach RAF base in April 1946.

Photo Royal Ordinance Survey. Annotations on the photo by Roger A. Freeman, Airfields Then and Now, 1978.

The 860th Bomb Squadron was formed on 14 September 1943 (it was disbanded on 28 August 1945). It joined Great Britain on January 1st, 1944 on a temporary base. It became operational on April 17, 1944 when it landed permanently on the Debach RAF base. Forty-eight hours ago, Lieutenant Digges and his crew completed their first bombing mission in the massive Operation Overlord over Normandy, which involved raining bombs on German coastal defenses. It was during this mission that the rear gunner, Sergeant Moe, contracted pneumonia, preventing him from flying today's mission to Nantes. He was replaced by Sergeant Jack Allen, who was the only person killed on the June 8 mission.

It is around 6:30 a.m. and the entire crew is at the foot of the bomber which, unlike other aircraft, does not have any nose art on its front fuselage that would allow its men to identify it. Lieutenant Digges, a few years later, during a visit to France, confirmed that his B-24 had a name, but that it was not yet painted on its front fuselage. He specified that his plane was called "Shady Lady" and not "Sweet Job".

2nd Lt Thomas DIGGES

With the final instructions given, it was time to enter the plane and take up one's position. Beforehand, excitement reigned around the plane. The bomb disposal experts filled the bomb bay. Ammunition was positioned at the various firing positions, 1,200 cartridges per machine gun, for a total of 12,000 cartridges. The ground crew, each according to their specialty, were busy preparing for the flight, maintaining the aircraft and refueling the enormous fuel tanks supplying the four engines. Orders from the control tower reached the pilots' headsets, who gave their final instructions to the crew while starting the powerful engines. The bomber moved into position in the queue. At the ground run-up, the aircraft vibrated with all its power. Lieutenant Digges activated the levers and released the brakes. The B-24 gradually lifts off the ground after covering three-quarters of the runway. The fog enveloping the base is not dissipating at the start of the day. All aircraft piloting is done by instruments. The planned gathering must take place over the sea. Despite the efforts of the 860th BS pilots, the gathering over the Channel could not be achieved ; only Lieutenant Digges's 943 crew joined another group. The other 14 aircraft scattered throughout were ordered to return to their base (see USAAF "secret" document in the appendices). In the middle of the Channel, the crews saw the escort fighters tasked with ensuring their protection arrive on their flanks. The crossing passed without incident. It was not the same when this entire air armada approached the northern coast of Brittany. The enemy anti-aircraft defenses were unleashed. The shots were too short, fortunately, and the shells, recognizable by their small black plumes, burst below. In sight of Nantes, the order was given to all crews to reduce altitude somewhat and prepare to release bombs. At a reduced altitude, the aircraft formation would be more vulnerable.

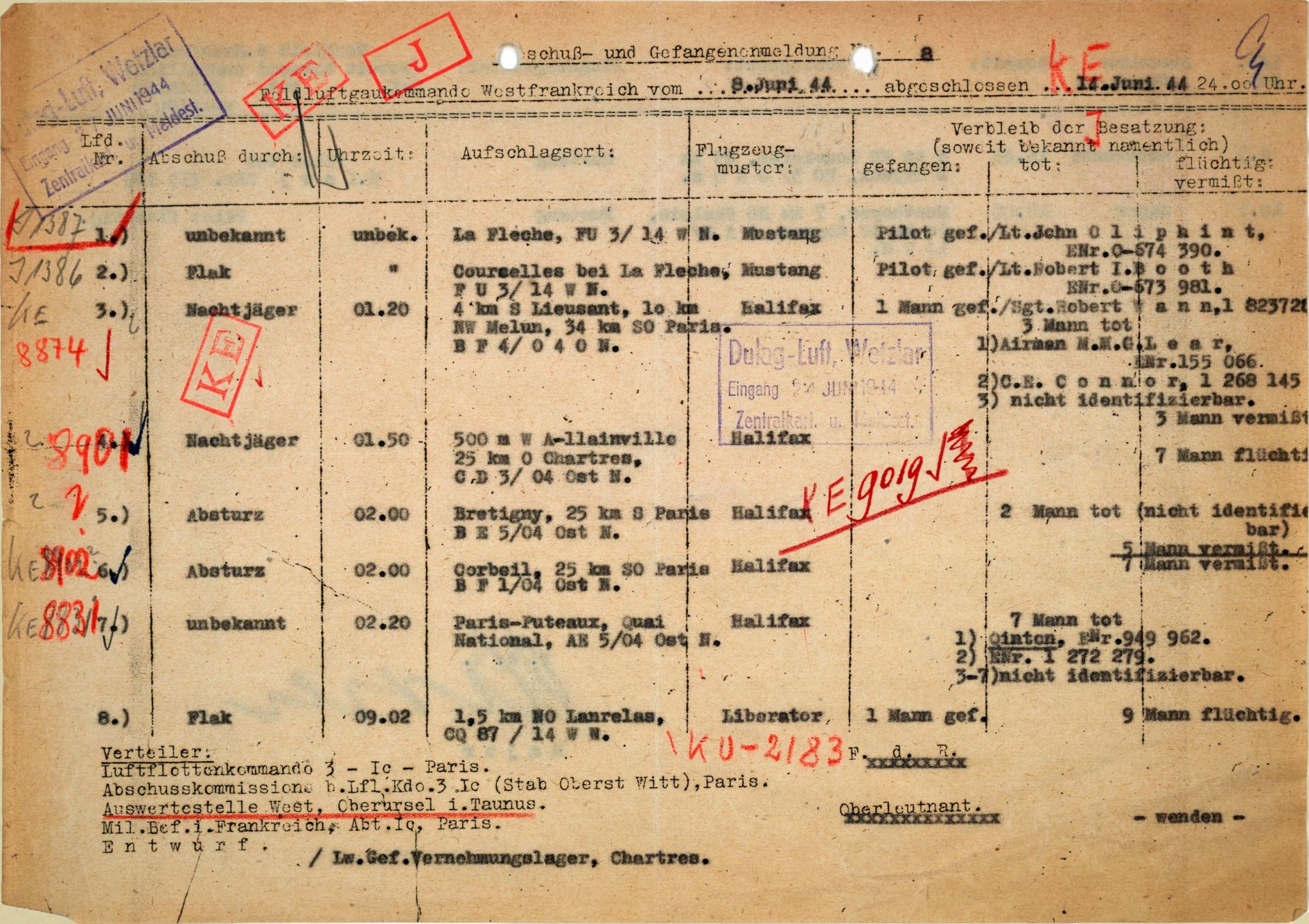

This German report informs us, on the last line, that at 9:02 a.m., a Liberator was shot down by the FlaK, that it fell 1.5 km to the

Northeast (NO = North Ost) of Lanrelas, that a man was captured (1 Mann gef = 1 Mann Gefangener = 1 man prisoner) and

9 men are on the run (9 Mann flüchtig)

It was a little after 8:30 a.m. when the formation arrived in sight of the target. The numerous FlaK (anti-aircraft guns) positions were unleashed and aimed at the American aircrafts. Clouds of intense black smoke, due to the shell explosions, invaded the airspace. The B-24 had opened its bomb bay. Suddenly, shells severely hit one of the engines, which immediately stopped. Then a second engine stopped. Shrapnel ripped through the fuselage, slightly injuring five crew members. Unfortunately, Sergeant Smith, the front gunner, was severely wounded in the right shoulder. He was bleeding profusely. Lieutenant Koller immediately came to his aid and tried to stem the bleeding while the pilot kept his aircraft within the formation, despite the problems. Unfortunately, a third engine was showing signs of fatigue. The aircraft passed just over the target. Lieutenant King operated the release handle, without success. Nothing happened. The cargo remained on board. The lieutenant quickly pressed the emergency circuit, still without result. The system was probably damaged by a shell. Immediately, the pilot decided to break away from the formation and quickly take the shortest route back. Very quickly, he realized that his B-24 was losing altitude (130 meters per minute) due to the lack of power of the last working engine and also to the weight of the unreleased load. Sergeant Reed, by radio, tried to contact the other aircrafts for protection. No one answerd his calls. The pilot and copilot tried to calculate the chances of bringing the aircraft back to its base or at least approaching the English coast in the hope of landing on water and then being recovered by the Royal Navy. To reduce the descent, an attempt was made to manually eject the bombs.

Left : on the site of this electric pole was built in 1944 the "Ville Gaston" house where Mrs Marguerite Le Derf had taken refuge to flee Rennes.

The B-24, evacuating its bombs before its fall, unfortunately let one fall on the house at this place

killing this poor woman and pulverizing her house. Today this place no longer exists on maps.

Right : bomb crater still visible.

Lieutenant King and Sergeant Cavestri slip into the cargo bay and, standing on the two metal beams, await Lieutenant Digges' order to evacuate them manually. The pilot tries to find a place where the projectiles cannot hit any residential area. The order is given, relayed by Lieutenant Koller. The bombs, one by one and quickly, fall to the ground. The first three fall on Chapelle-Blanche, between the hamlets of Ville-Sicot and Poirier. An excerpt from the book "Si Médréac m'était conté" ("If Médréac Told Me"), by Joseph Verger, recounts : "Denis Leroux, now living in La Forestrais, is just around the corner. Like children his age, he spends his time looking for blackbird nests along the hedges. A completely free pastime. The noise is deafening and suddenly, a cloud of earth falls on the shoulders of the terrified Denis, who is completely frightened. ". Other bombs fell on Guitté and Saint Jouan de l'Isle at the place called ''Pont des Arches''. Unfortunately at La Chapelle Blanche, at the place called ''La Ville Gaston'' one of them hit a house where a woman and her son, refugees from Rennes, lived. Mrs Marguerite Le Derf, nee Chomard, was killed instantly. Her husband, who had gone fishing at Perrières, was unharmed. At that moment, the bomber in distress was overhead the town of Médréac, in Ille et Vilaine (35 km northeast of Rennes); despite all efforts, the B-24 would not be able to cross the Channel.

Aerial view of the hamlet of Bodinais from the 1950s. The B-24 crashed a few meters south of the hamlet, in a field.

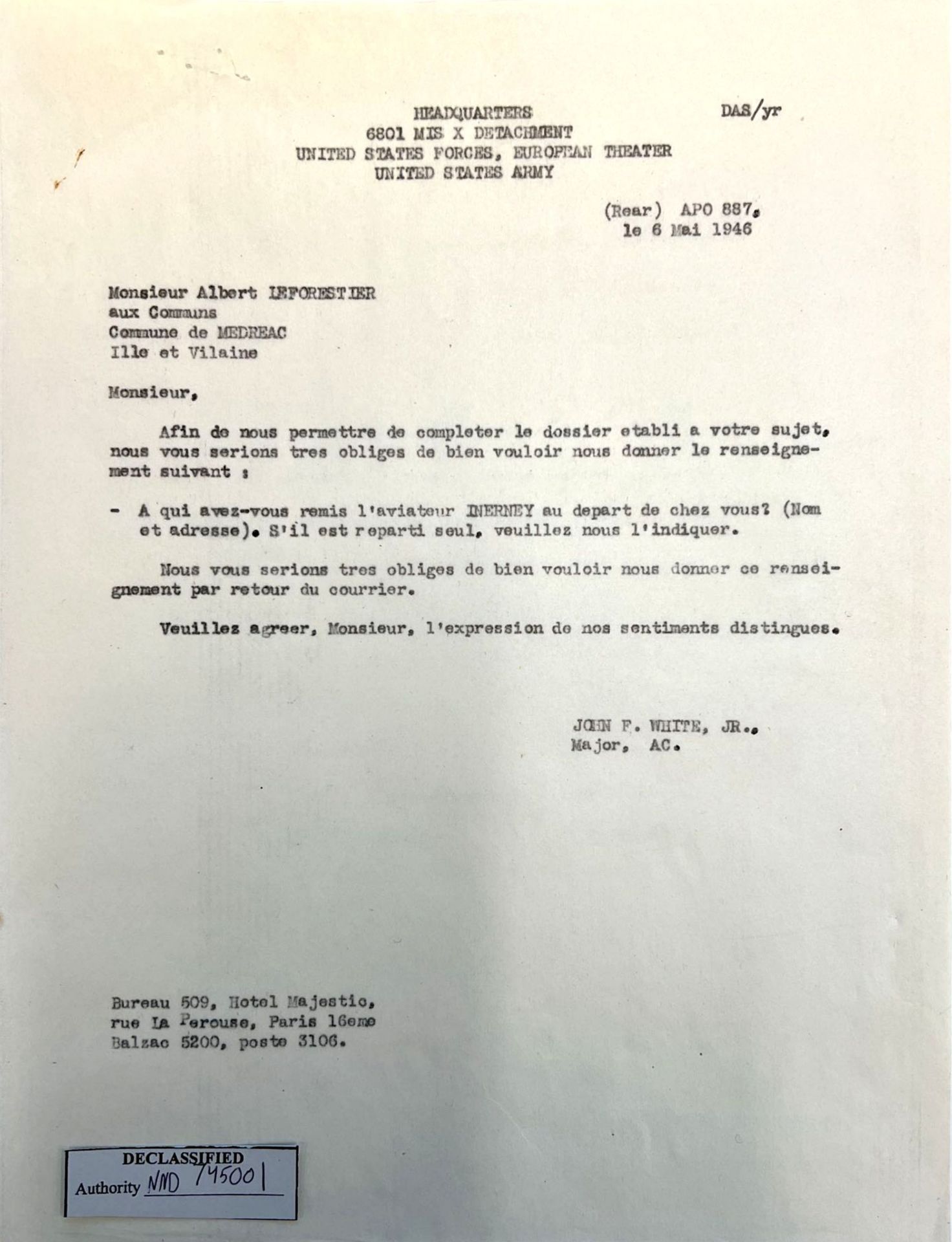

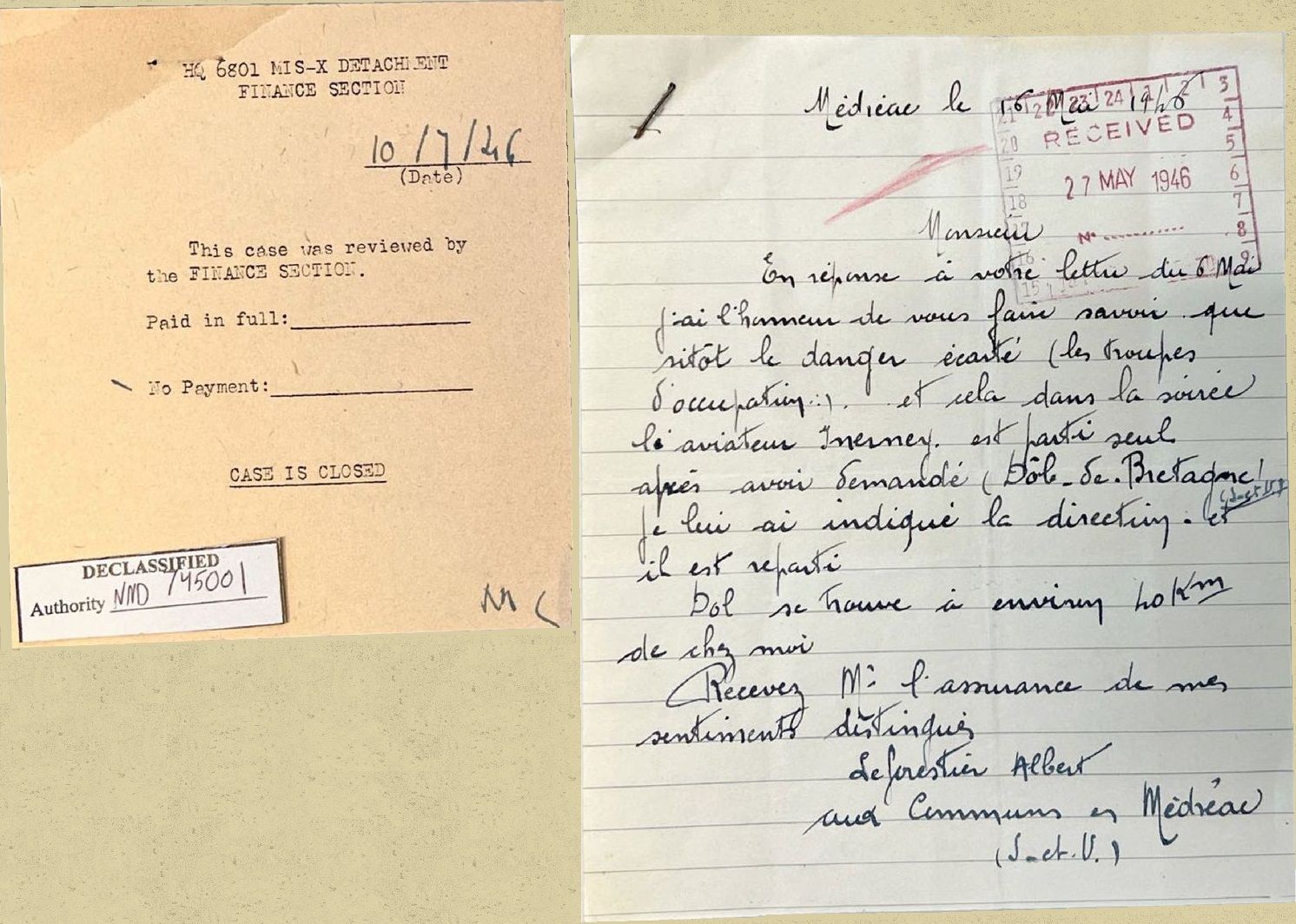

It is exactly 9:00 a.m. Lieutenant Digges decides to order his entire crew to quickly leave the aircraft while respecting a time gap between them that will allow them to disperse into the surrounding countryside, making them more difficult for the enemy to locate. Each airman busies himself putting on his parachute, checking each other to ensure that his comrade's parachute is properly in place and secure. Sergeant Allen is the first to jump into the void. He is followed by gunner McInerney. In Médréac, from the church bell tower, German snipers unleash fire on the two airmen, fortunately without hitting them. Then they leave the bell tower and head towards the Coterel farm, run by the family Lecorvaisier, thinking that the paratroopers are hiding there. Anne-Marie and Ernest Lecorvaisier as well as their 3 children Berthe, Ernest and Henri are threatened and held at gunpoint against the wall of the house, while the Germans search the house and the outbuildings ; they find nothing. McInerney falls in a wheat field, at the edge of the "Bois de Limpéran" (Imperant woods), behind the house of "Hauts Communs". He is away from any road. Sergeant Allen lands near a country road leading to the farm of ''Coterel'', unfortunately in a thick holly hedge, on which his parachute canvas gets caught. He remains suspended a few meters from the ground and unfortunately for him, the Germans who came from Médréac in motor vehicles, who had just searched the Lecorvaisier farm, arrest him immediately.

Thomas Senan McINERNEY.

Photo Deborah Sullivan (nee McInerney)

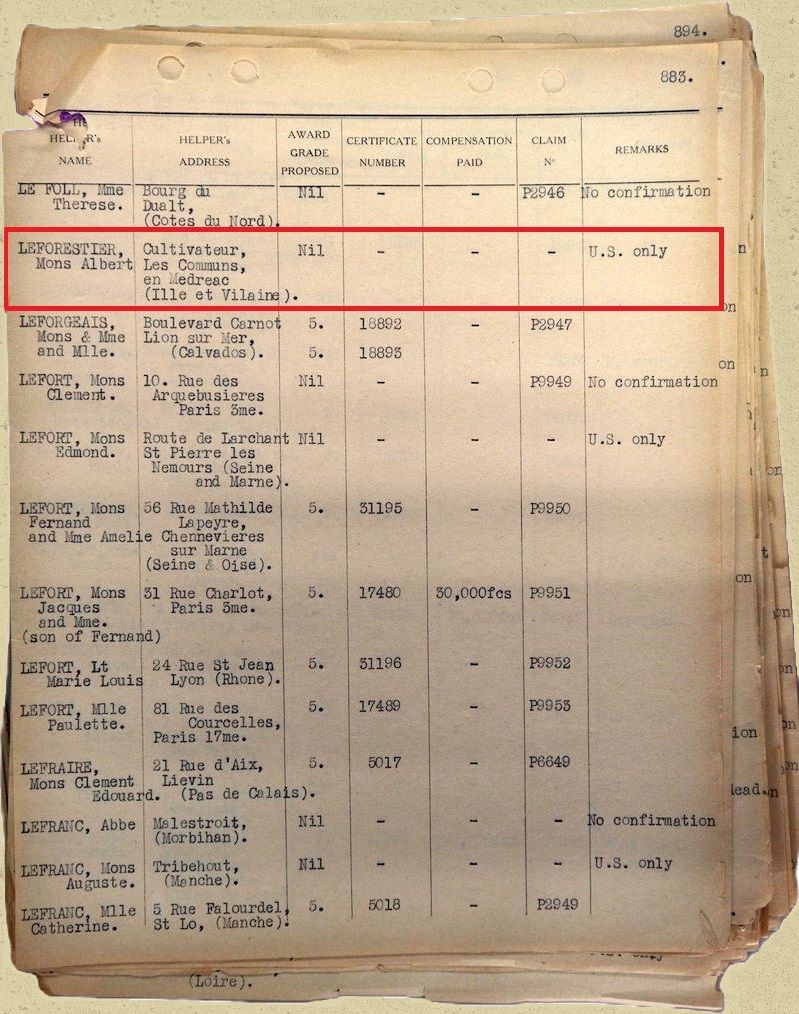

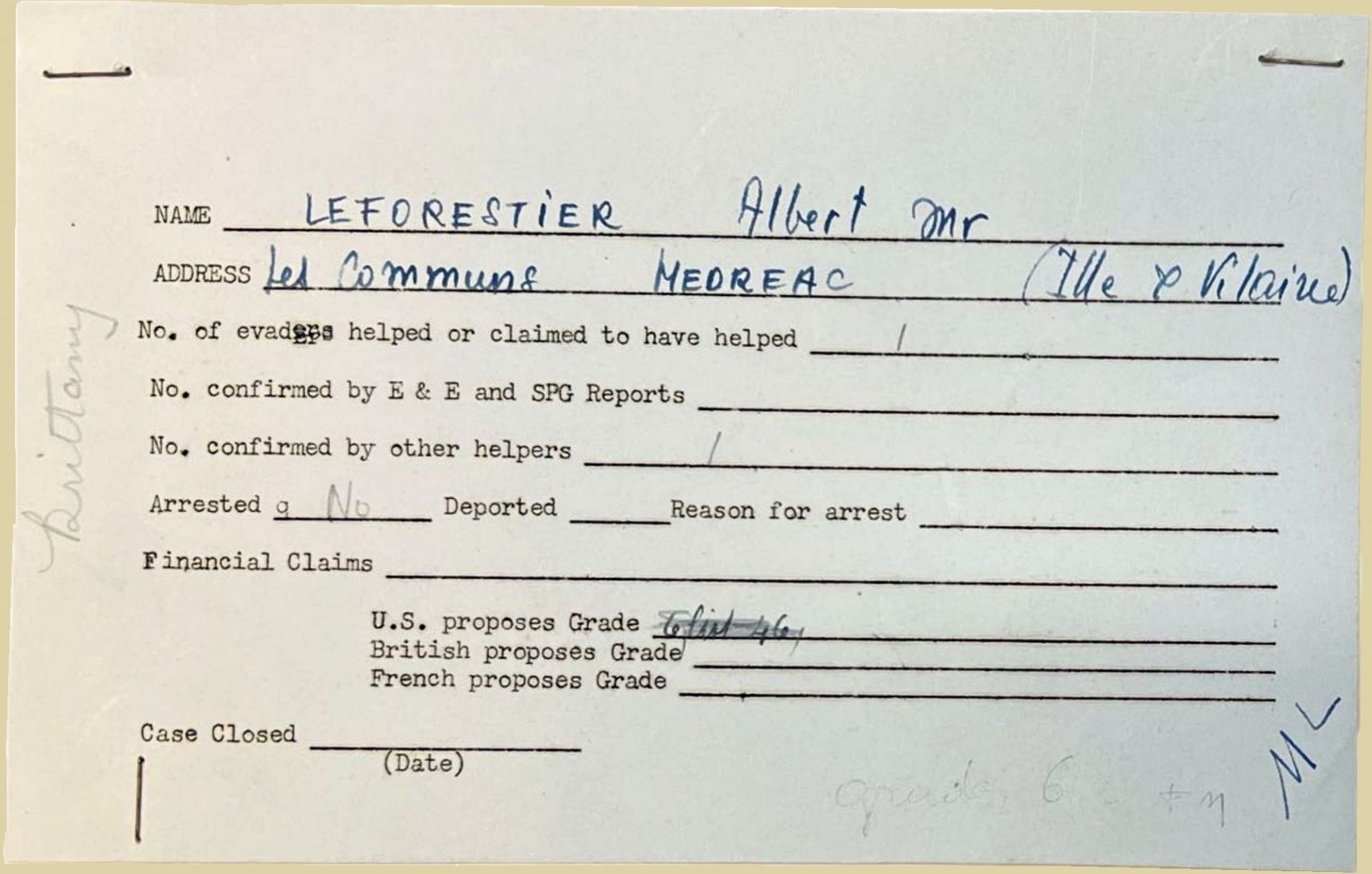

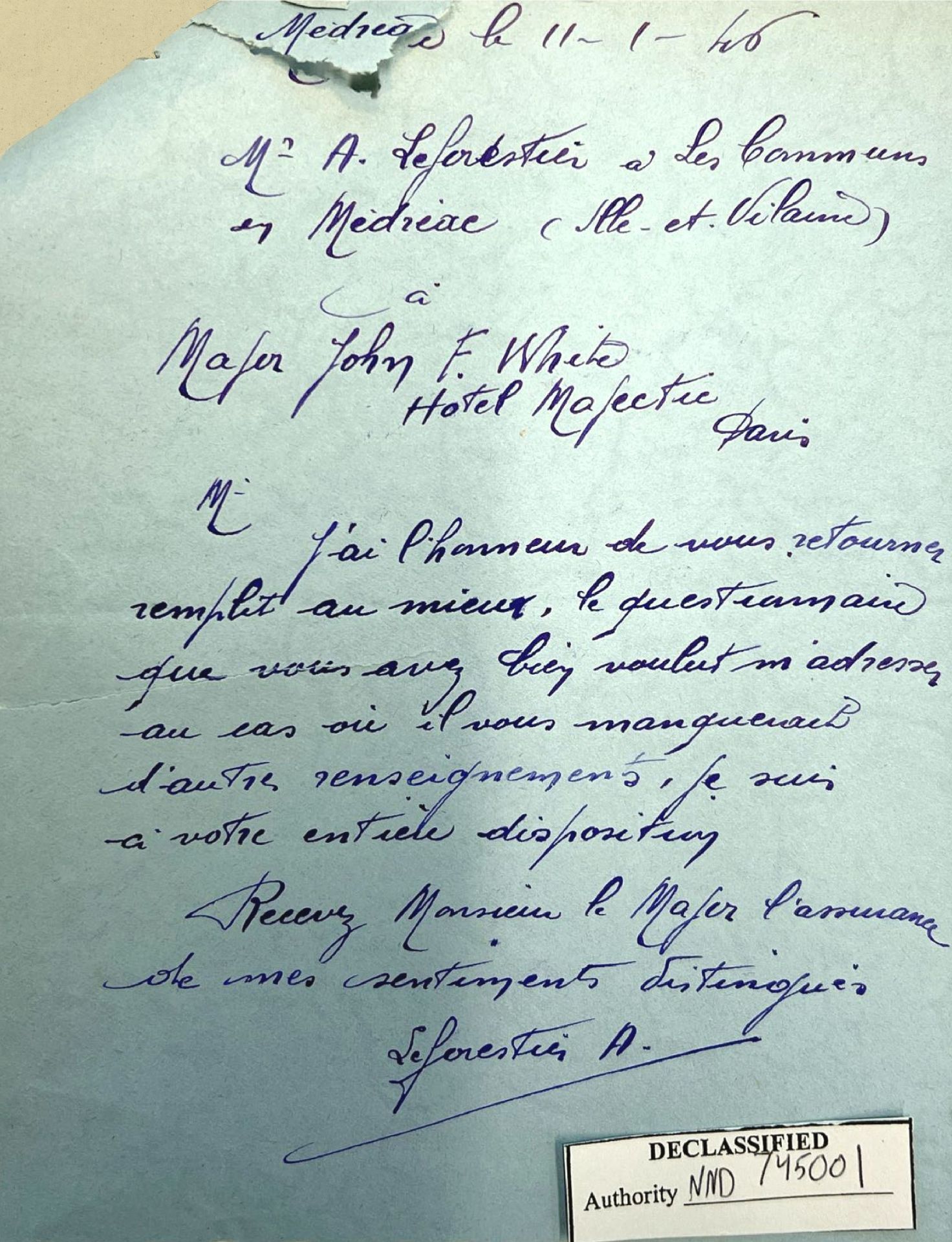

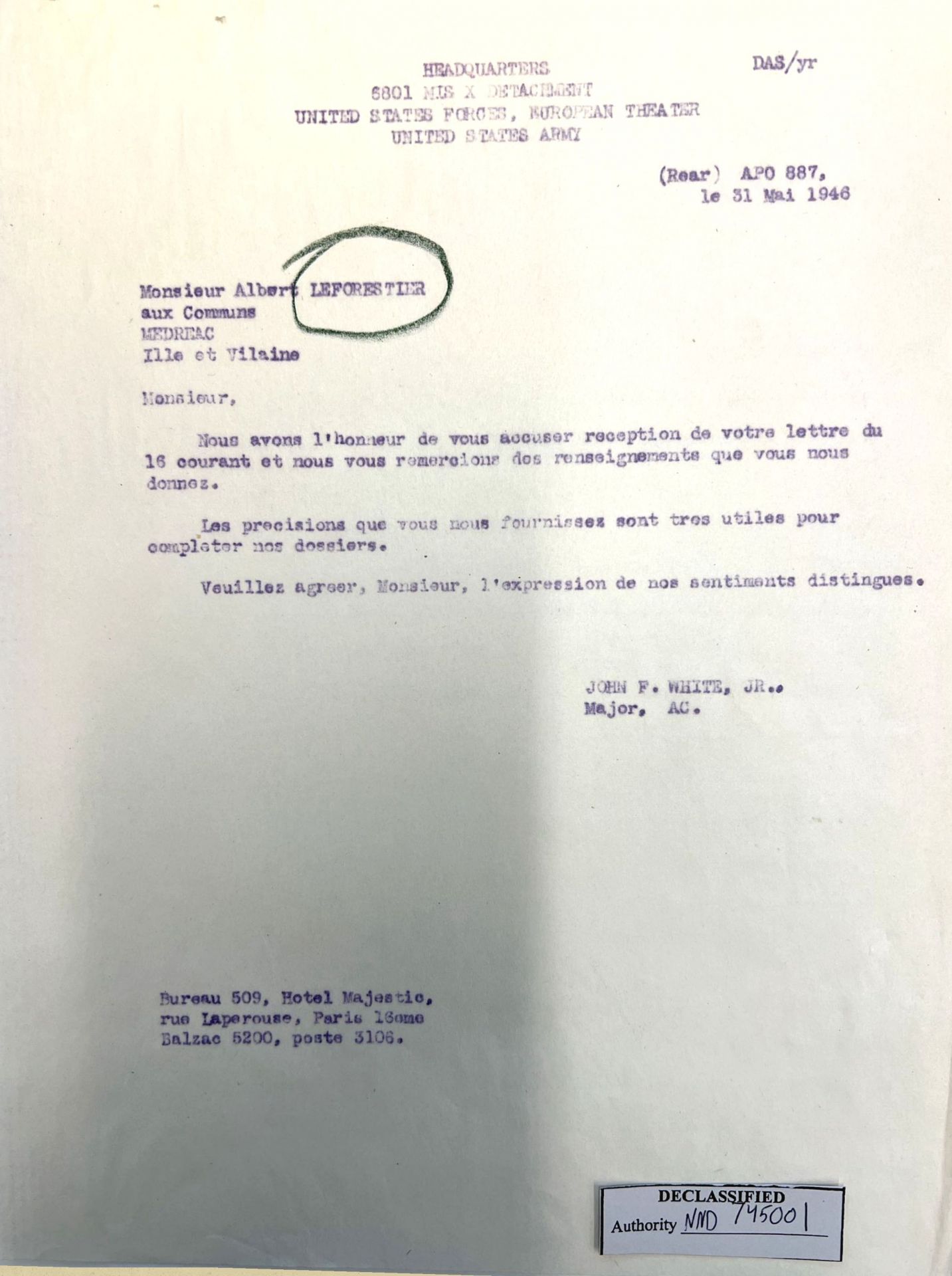

Sergeant McInerney makes his way through the wheat, taking care to raise the stalks to conceal his trajectory. He has not forgotten to retrieve his parachute to hide it in a furrow. This will remain hidden until the liberation and was then used to cover the canopy during the processions on Corpus Christi. Arriving on a path, a man and a teenager wave to him, asking him to come towards them. He complies and arrives in the small farm of a farmer, Mr Albert Leforestier, who lives with his sister Angele and their nephew Roger, aged 15. The latter immediately provided him with civilian clothes, a black beret and shoes, which were too small ! McInerney quickly changed while Angèle Leforestier prepared some pancakes for him to eat with cider ; Albert, seeing the Germans approaching, hid the aviator's uniform in a fertilizer bag under the bed. It was then that the Germans entered the farm and began to search the place. A German arrived in the kitchen, finding this man at the table. He asked him "Paratrooper ? Where is Paratrooper ?". "No paratrooper" Albert replied. The German shrugged and left immediately. The Germans quickly left. It was a sigh of relief that led McInerney to another hiding place in an attic above the pigsty. McInerney then hid in the surrounding woods or went to the fields with Albert. After a few days, he wanted to leave by walking and asked Albert Leforestier for directions to Dol-de-Bretagne, thinking he would join the American troops in Normandy. He would be stopped by the enemy in the Dinard region (see below his testimony collected in 1995). The B-24 continued its final flight, with Lieutenant Digges still at the controls. The aircraft had just flown over "La Chapelle Blanche" then "Saint Jouan de l'Isle" and was heading towards Plumaugat. The order was given to airmen Bolin, Fischetti and Koler to bail out, an order they carried out immediately.

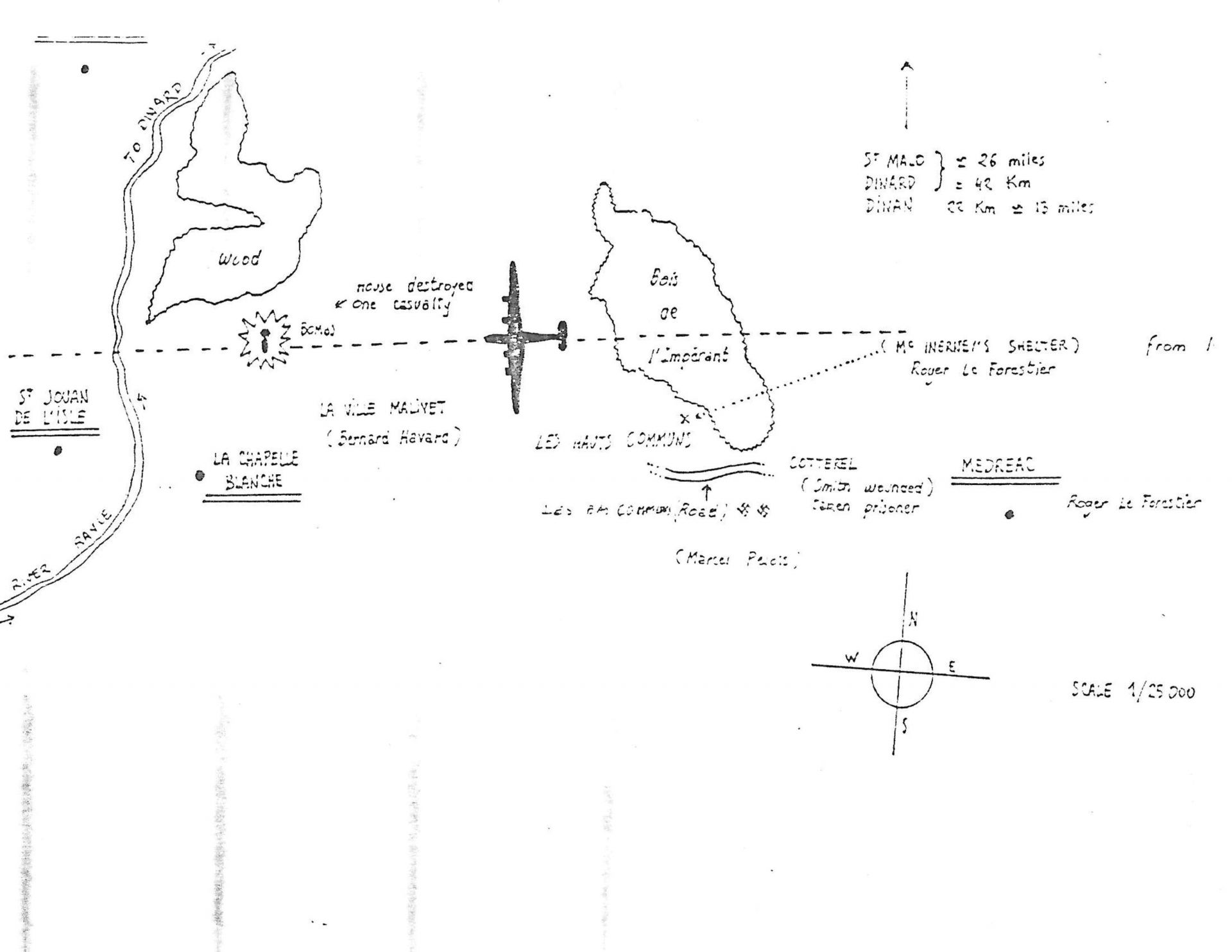

This map drawn by Thomas McINERNEY provides information on the aircraft's path before its crash. It shows :

- the route from Médréac to Saint-Jouan de l'Isle

- 2 swastikas at "Bas Communs" which probably indicate the place from which the Germans spotted ALLEN and McINERNEY falling by parachute.

- The " Bois de l'Impérant" (Imperant Wood) where McINERNEY hid during the day

- the White Chapel and the place where Mrs Le DERF was unfortunately killed by a bomb dropped by the crew.

The text states "house destroyed - a loss"

- the "Hauts Communs" where the shelter of McINERNEY and Roger LEFORESTIER was located.

- The Hamlet of "Cotterel" where it is mentioned that SMITH was wounded and captured.

Document Deborah Sullivan (nee McInerney)

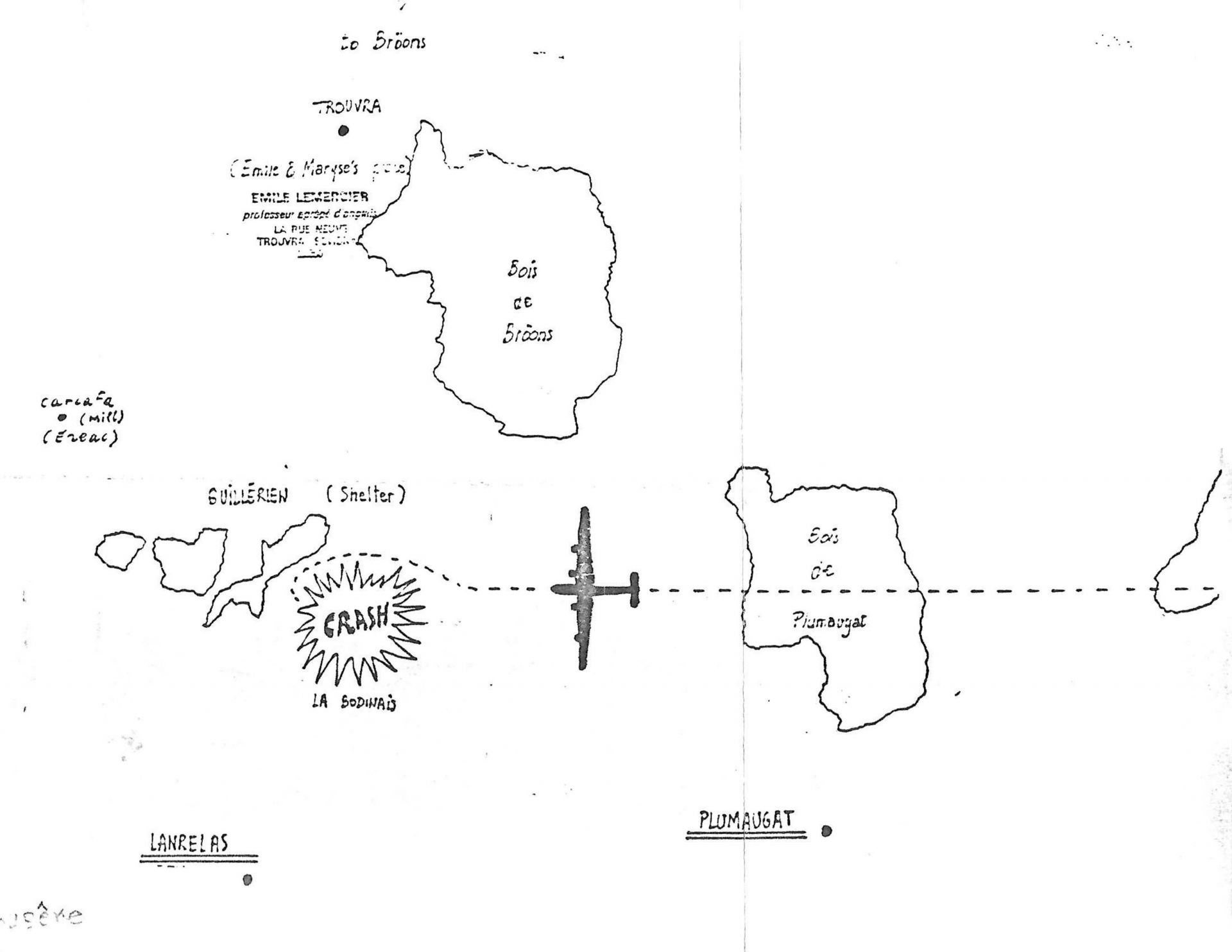

This second plan gives indications of the location of the aircraft's crash site, at "Bodinais", after the "Bois de Plumaugat" (Plumaugat's wood)

It shows the location of the "Carcafe mill" in Eréac.

Document Deborah Sullivan (nee McInerney)

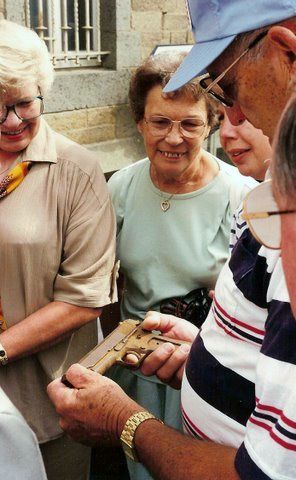

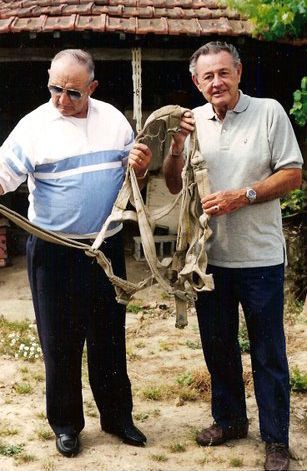

2nd Lieutenant Bolin landed near the village of "la Bichetiére" and was hidden at the nearby farm of Saint Maleu. Sergeant Fischetti fell near the place called "La Thézelais". These two villages are located north-northeast of Plumaugat. 2nd Lieutenant Barney Koller was very scared during his parachute descent. He saw his bomber turn around and come back towards him. Fortunately, the aircraft fell to the ground before and at a distance that put him out of reach. On board the aircraft, Sergeant Smith, injured, was helped by Sergeant Reed. They bailed out together. Lieutenant Digges advised Smith to surrender as soon as he reached the ground, given his injuries. The two men landed in the village of "l'Heume," north of Lanrelas. Reed was busy removing his parachute harness when they saw a farmer's wife heading towards them. Arriving in the farmyard, and knowing his comrade was safe, Sergeant Reed said goodbye to his friend and quickly went into hiding. The farmer, Madame Menard, took care of the injured man and made him comfortable in her home.

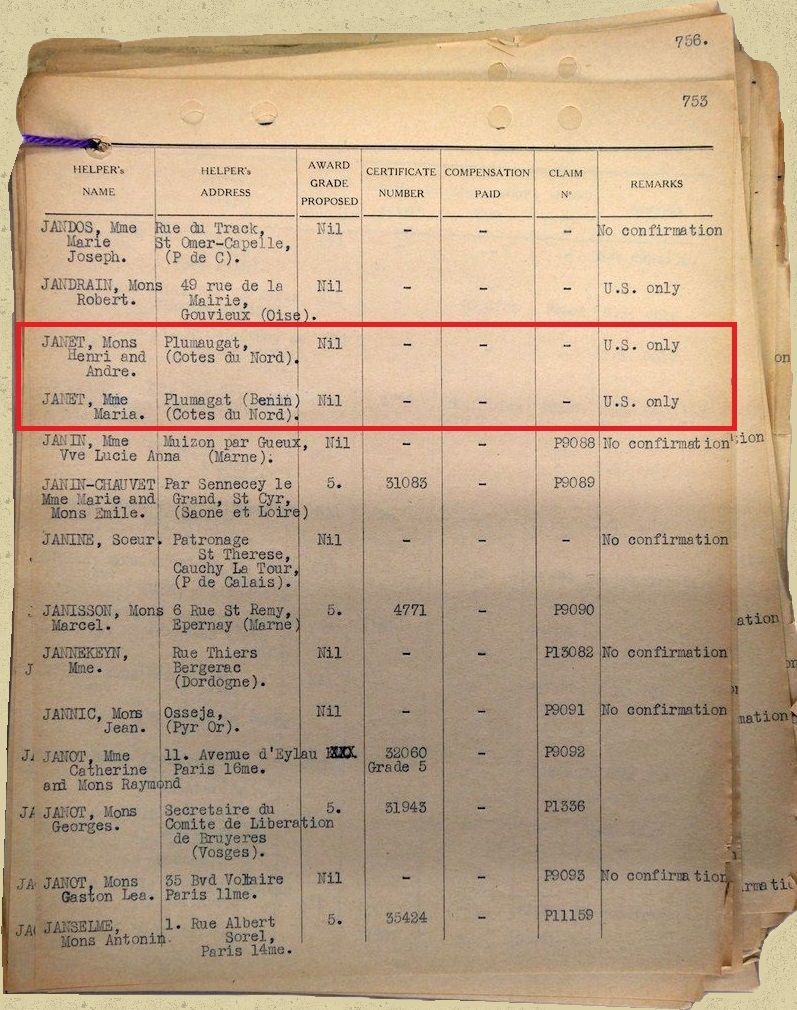

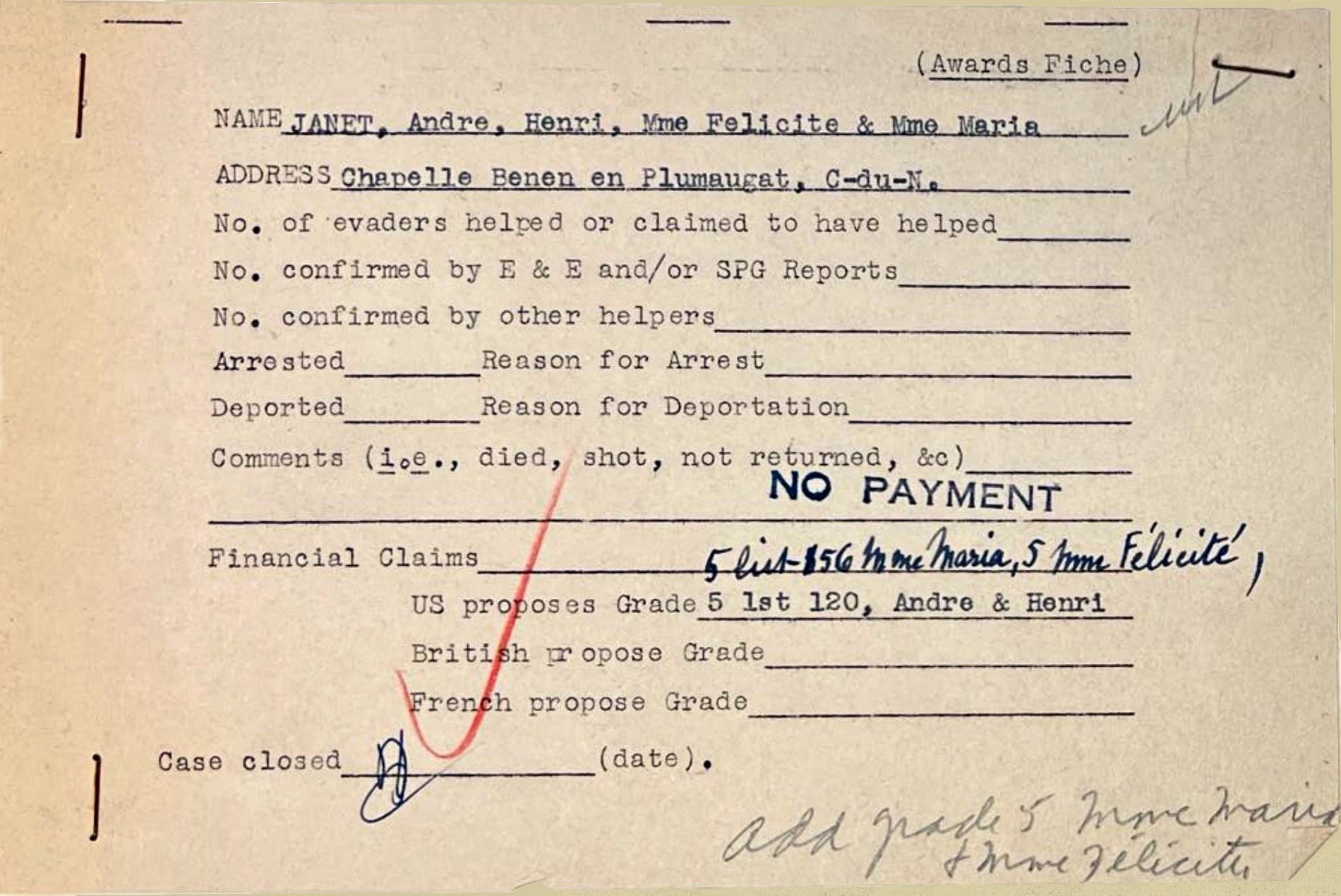

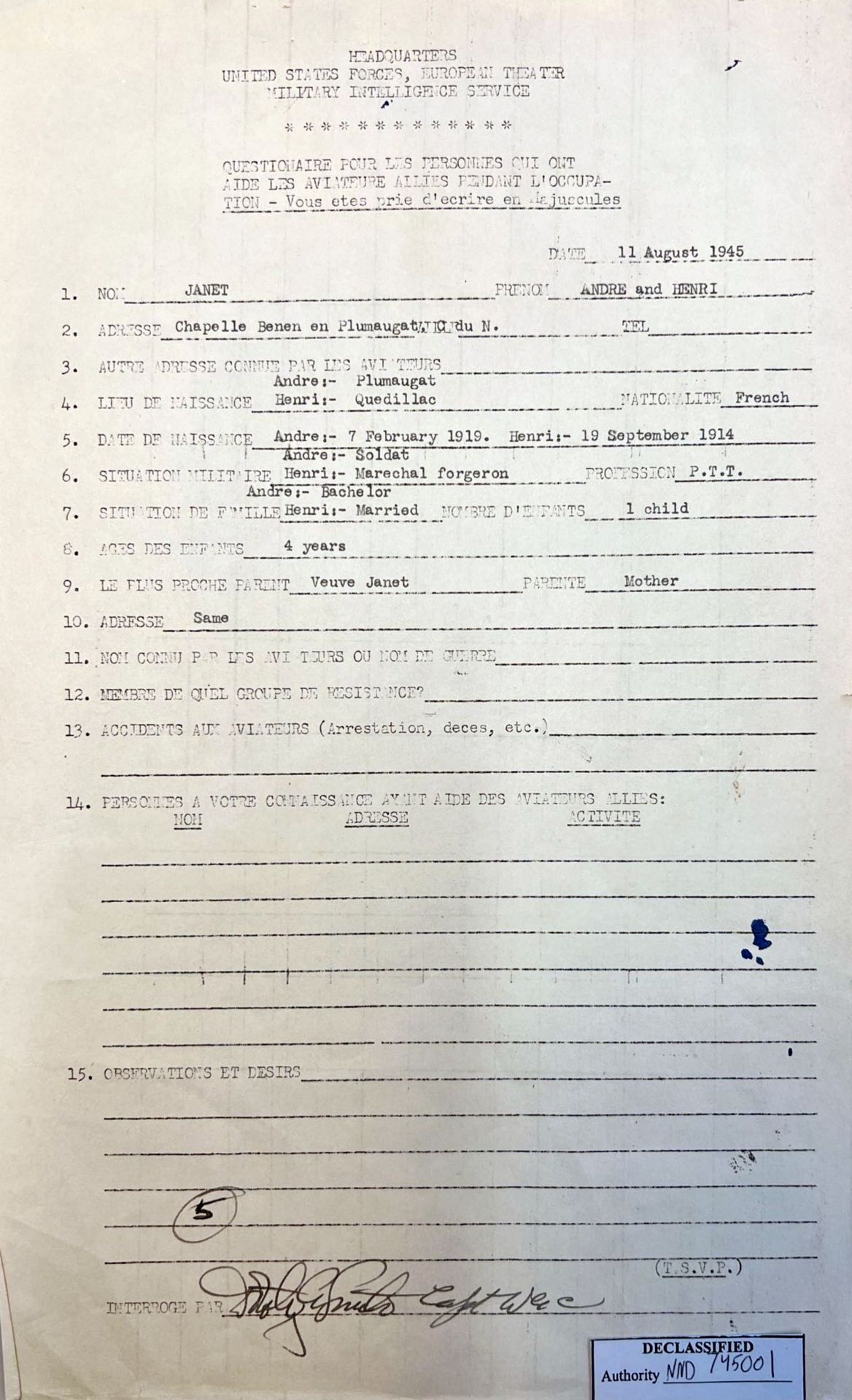

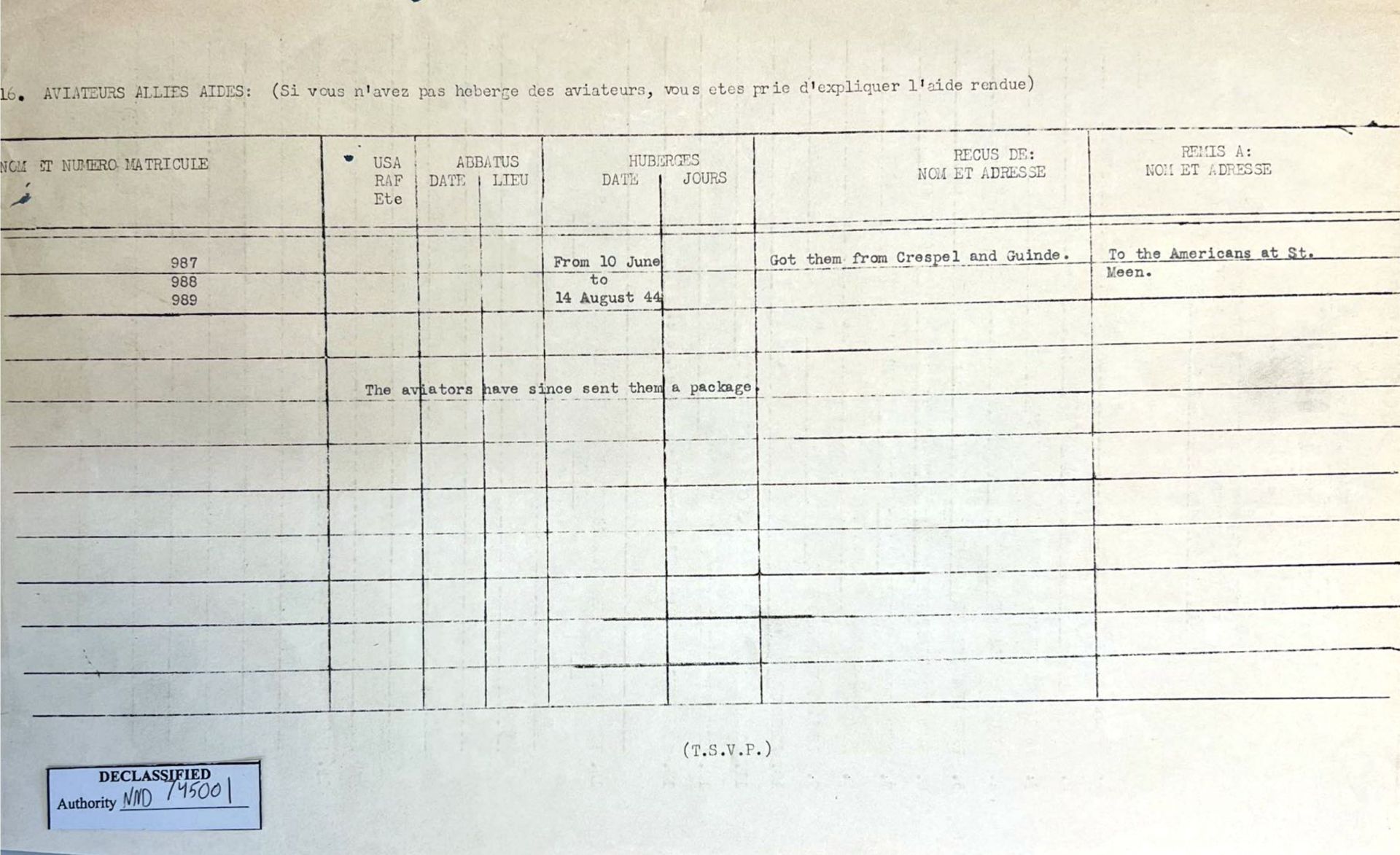

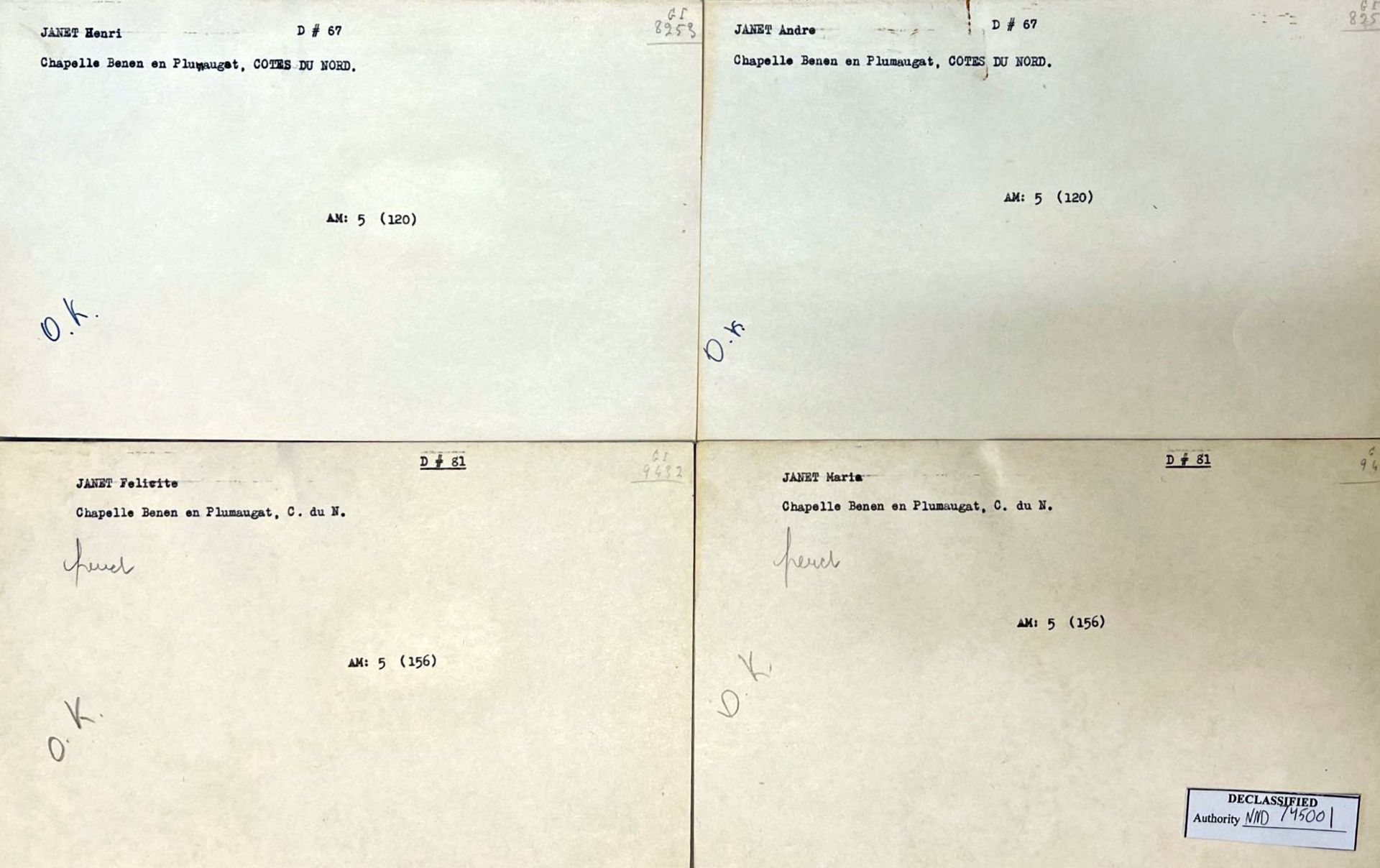

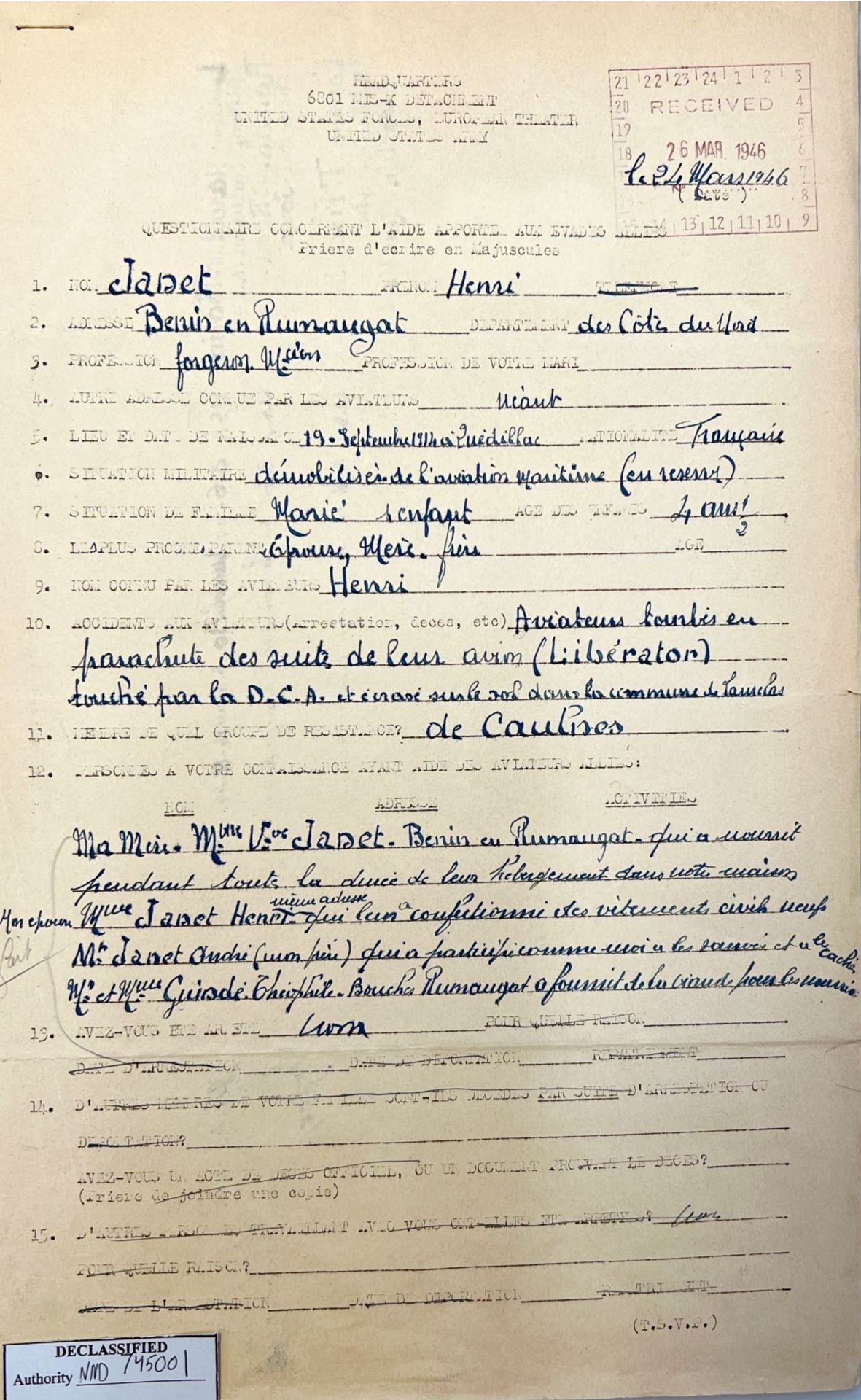

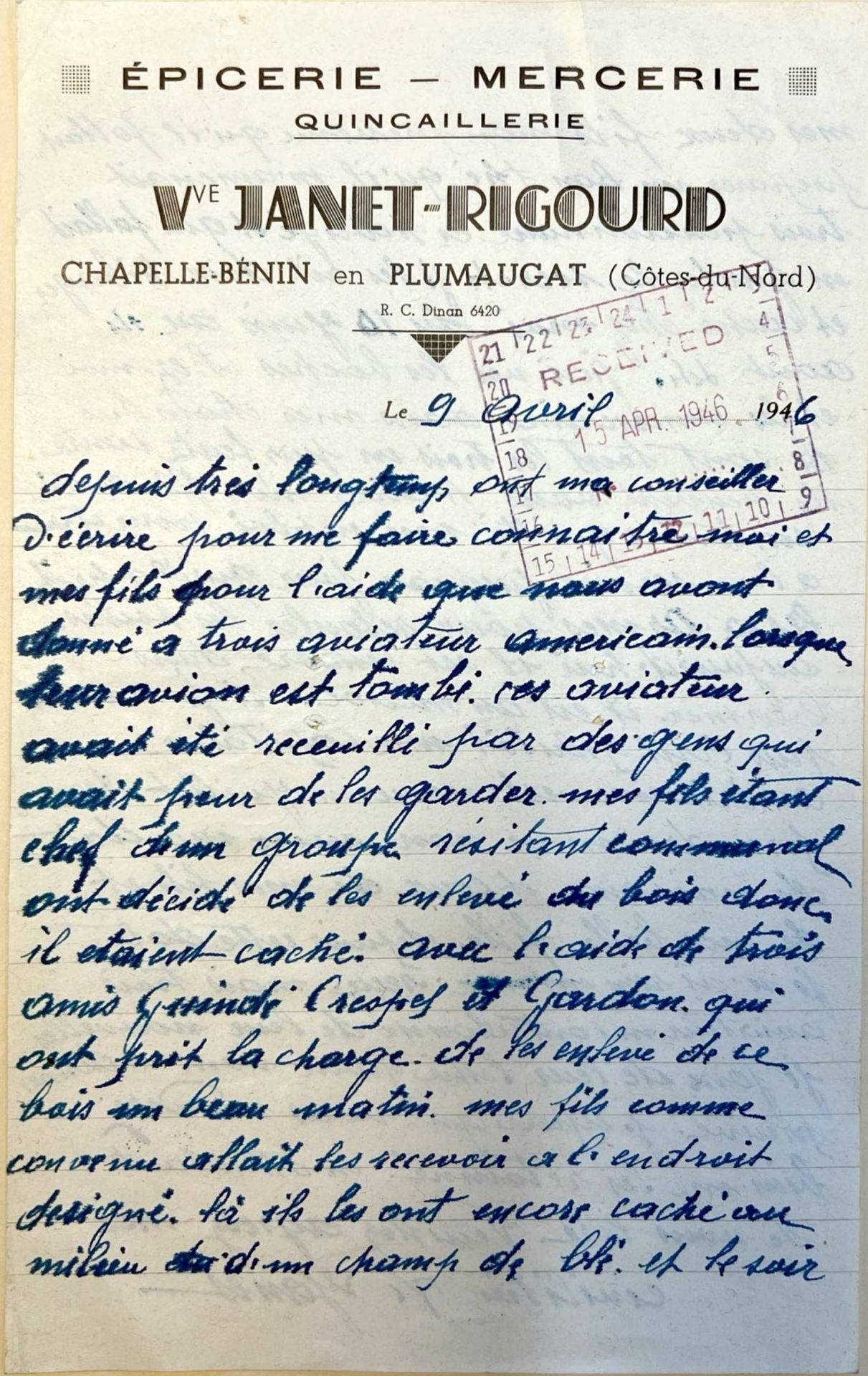

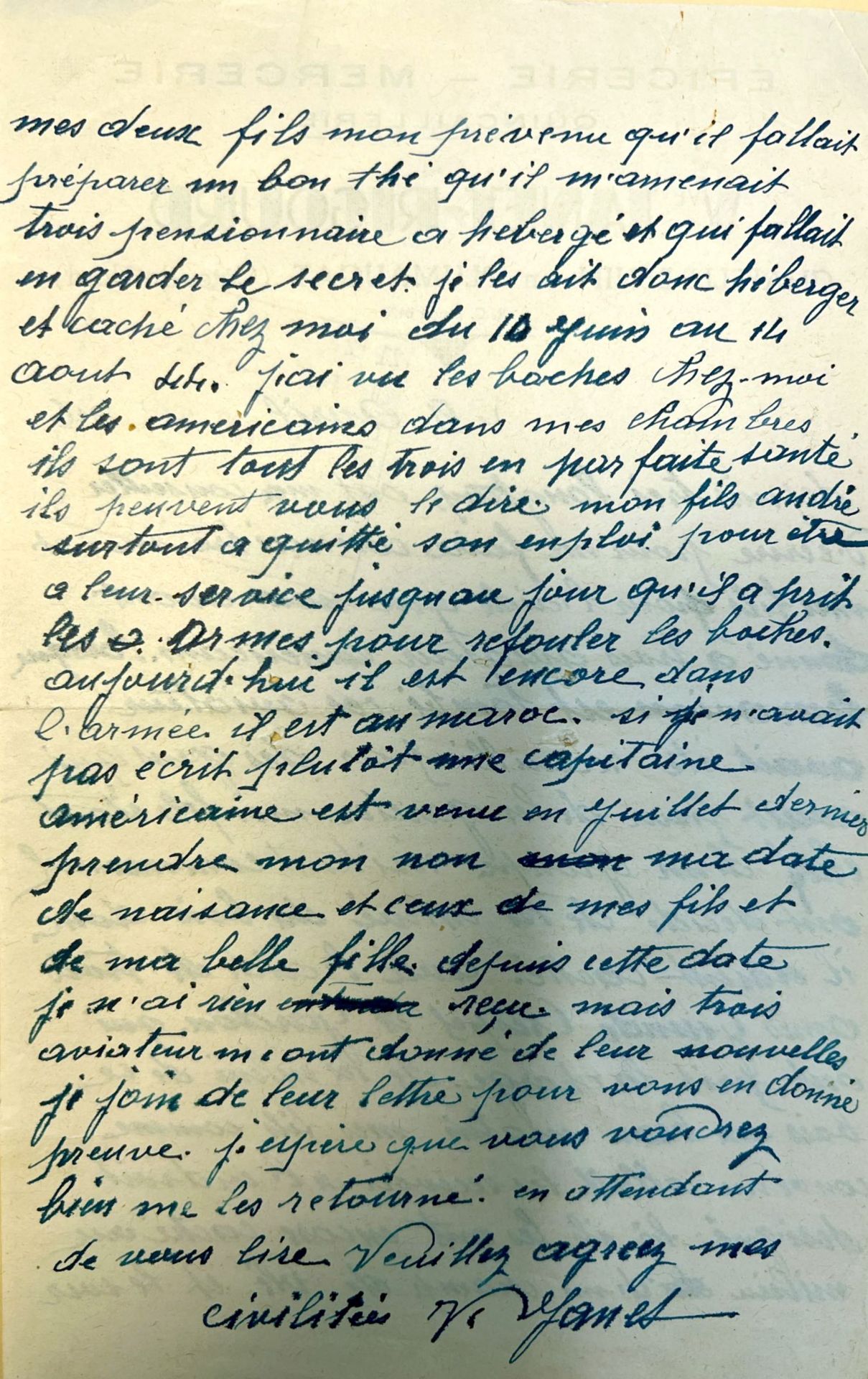

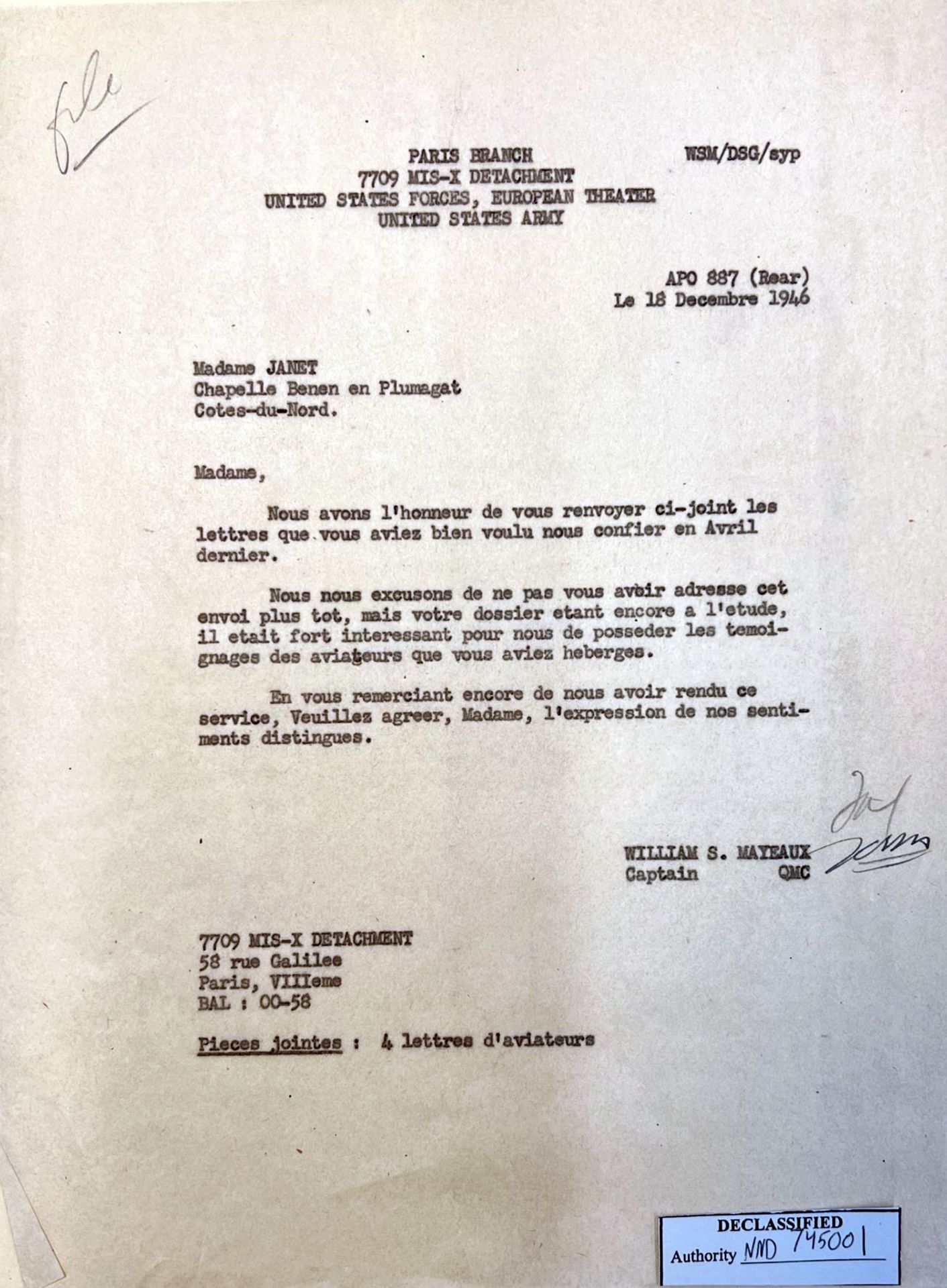

2nd Lt Harold BOLIN

The Germans, on alert, were quick to recover their second prisoner. 2nd Lieutenant King and Sergeant Cavestri also bailed out into the void. For Cavestri, the arrival was particularly brutal because he arrived at the farm of Mr François Gervaise (who witnesses this scene) in the village of "Guillerien". His parachute catched on the roof of a barn, violently pinning him against the wall where he was knocked unconscious. The farmer took his ladder and quickly climbed the bars to come to the aid of the aviator. Cavestri left his delicate position after regaining consciousness. The parachute was quickly hidden by the farmer. 2nd Lieutenant King, meanwhile, landed at the edge of a field about 800 m from his comrade. 2nd Lieutenant Digges was now alone on board. He too was thinking of ejecting because time was running out. He left his aircraft, throwing himself into the void. The bomber began a sharp turn to its right, flying over the villages of "Vieux ville", "Beaumont", "Clin Julien", "Le pont du Breuil", "Queloscoet" to come crashing down on the edge of a road between the villages of "Châtel" and "Bodinais". It is 9:30 a.m. Resistance fighters recover airmen Bolin, Fischetti and Reed and quickly hide them in a large wood near Plumaugat. Unfortunately, someone who is not very discreet reveals the existence of the Americans and it is urgent to evacuate these friends from the sky to another hiding place. On June 10, at 4 a.m., the resistance fighters, Mr Crespel, Mr Gardon and Guinde wake up the three airmen who seem very worried about this early morning awakening. Bolin, who understands and speaks a little French, reassures his companions and together they head towards the village of "Benin" where they were welcomed by Mrs Janet Their hiding place was a shelter dug at the bottom of the garden.

2nd Lt Harold W. BOLIN, T/Sgt Ronald Westler REED and T/Sgt Carmine T. FISCHETTI hidden in the village of Bénin.

2nd Lt Harold W. BOLIN, T/Sgt Ronald Westler REED and T/Sgt Carmine T. FISCHETTI dressed in civilian clothes.

Photos taken by Carmine T. Fischetti, from his escape report

BOLIN, REED and FISCHETTI with the JANET family

Photos taken by Carmine T. Fischetti, from his escape report

Mrs JANET's house in the village of "Bénin" in Plumaugat

Photos taken by Carmine T. Fischetti, from his escape report

Mrs widow JANET and one of her sons, Henri JANET

Photos taken by Carmine T. Fischetti, from his escape report

Carmine T. FISCHETTI and André JANET Mrs widow JANET, Marguerite a neighbor, André JANET,

Henri JANET and in front, on the right, Marie JANET, Henri's wife

who holds her granddaughter's hand

Photos taken by Carmine T. Fischetti, from his escape report

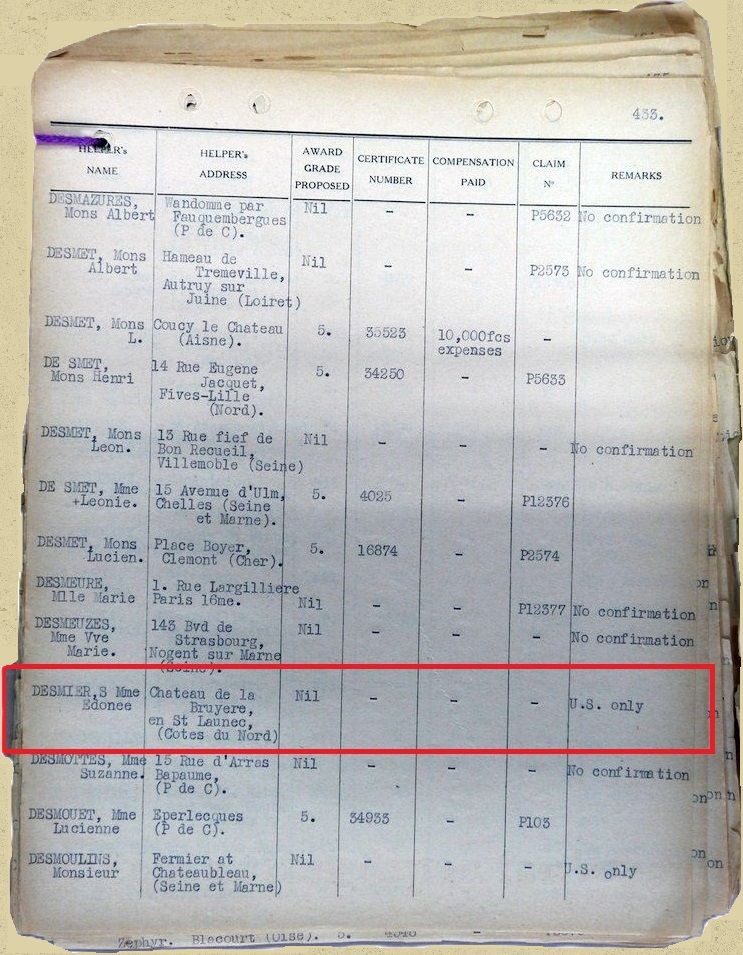

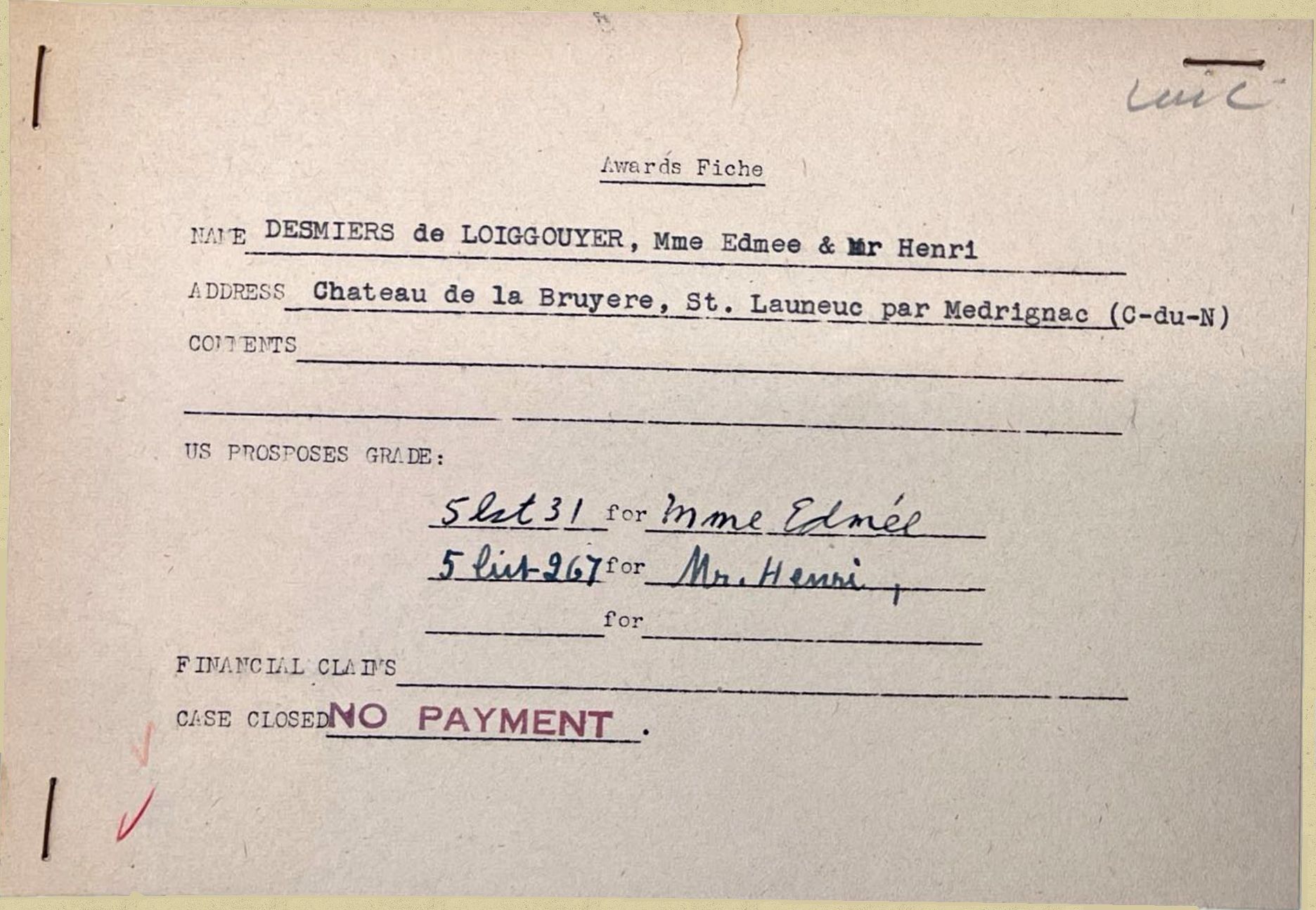

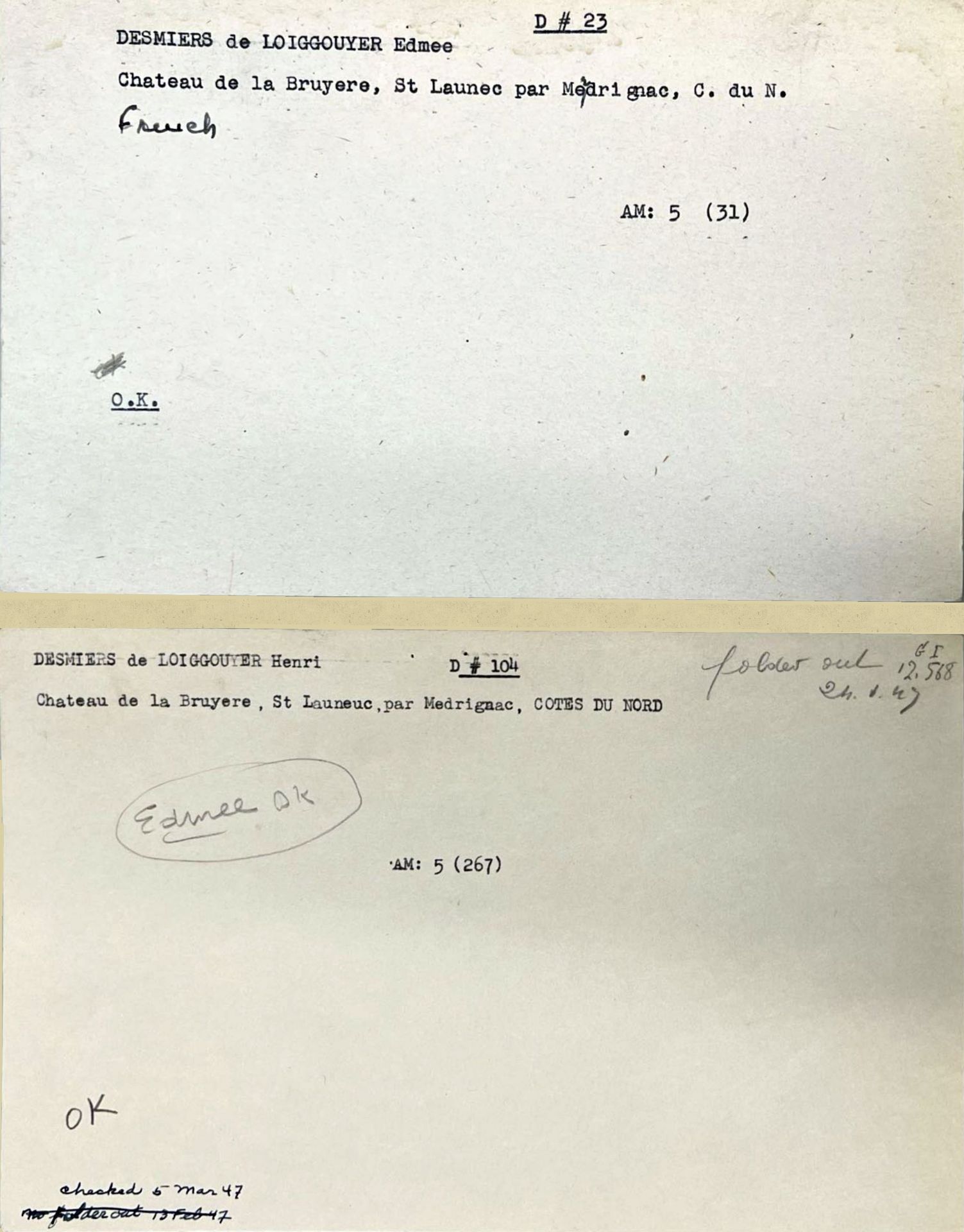

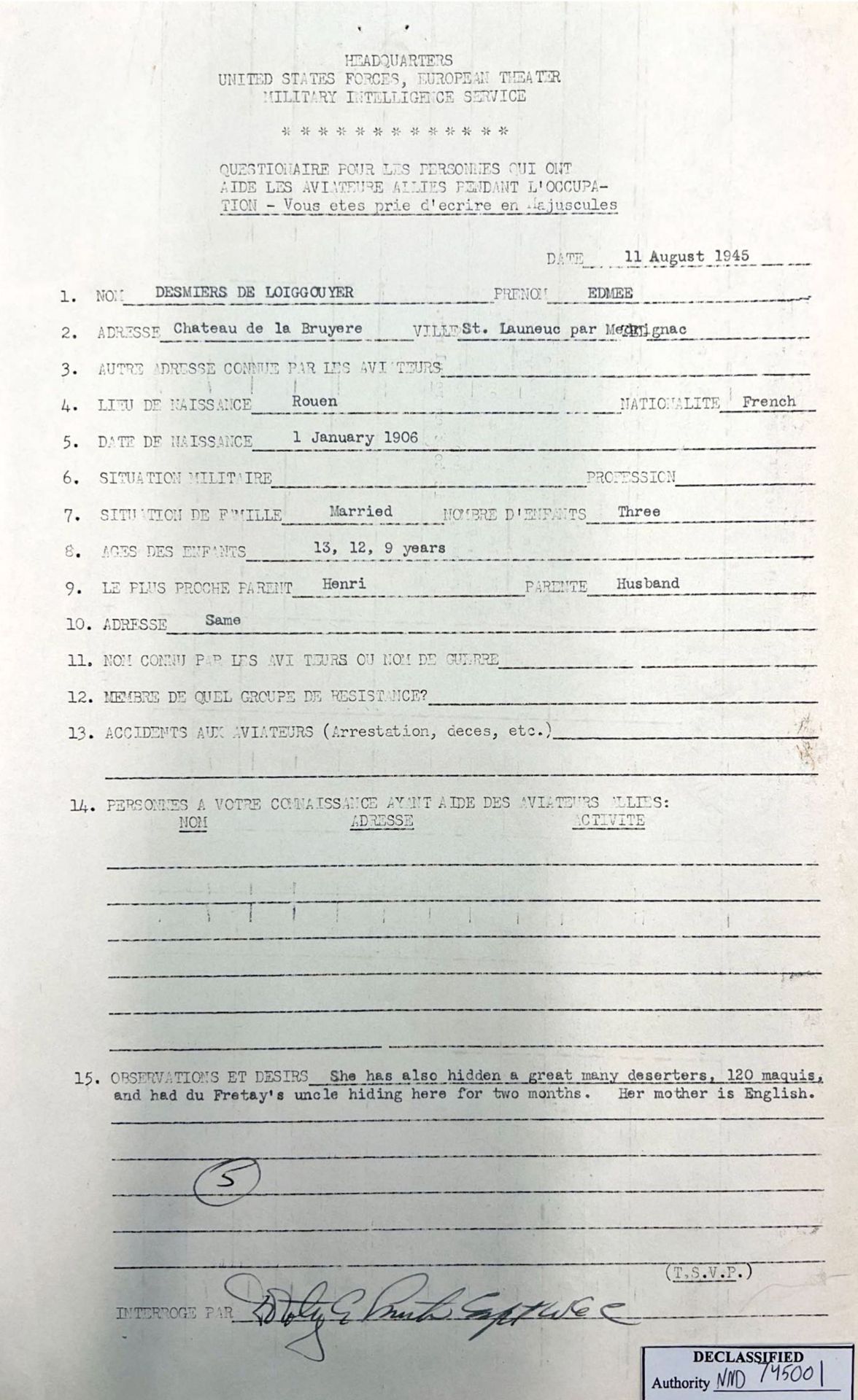

Lieutenant Digges, with King and Cavestri, find themselves at the "Carcafa Mill". The miller, Mr Craboulet, hides them and feeds them for a few days ; but the mill is small and he fears for his family. Mr Desmiers, from Ligouyer, is contacted. He lives at the "Château de la Bruyère" in Saint-Launeuc. He agrees to take charge of the three Americans. Opposite his castle, the large wood will be ideal for hiding them. A tent is installed in a hole dug among the trees. They are now safe. The three children of the house are kept away from what is happening. Mrs Desmiers prepares meals for everyone, including the "guests" ; however, the second son of the house finds his parents' new habits strange and one day he checks the contents of the basket. His mother surprises him and calls her husband who asks his son to forget what he saw and to promise not to tell anyone and that later he would explain to him. The secret was well kept.

The "château de La Bruyère" in Saint-Launeuc (Côtes-d'Armor), where airmen Digges, King and Cavestri were hidden in June 1944.

This castle is now listed as a historic monument.

Photo Thérèse Gaigé via Wikipédia - (photo credit according to Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International).

A few days later, the Resistance came to retrieve the three airmen and directed them to the Bourgneuf maquis. They remained there until the arrival of American troops heading for Brest in early August 1944. However, during their stay in the region, the American airmen were able to meet their comrades hidden in other places. An interview organized by the local resistance took place near the Loziers pond. As for 2nd Lieutenant Koller, he remained alone after landing on French soil. He managed to change his clothes, helped by some courageous farmers. He headed south. After days and days of walking, he found himself in the Dordogne, where he was taken in by members of a resistance movement. Incorporated into this troop, he fired several shots against the occupying forces. One

night, an aircraft from England on a mission landed and picked him up along with several other Allied soldiers who had escaped to France.

As for Sergeant Allen, his story was unfortunately tragic. Aa a prisoner of the Germans, he was aboard a truck on a road leading to a Stalag in Germany when a group of 6 Spitifires rushed towards the truck. Allen was killed instantly. Sergeants Smith and McInerney found themselves prisoners in the same Stalag Luft (prisoner for air camp), from where they did not return until after the end of the war.

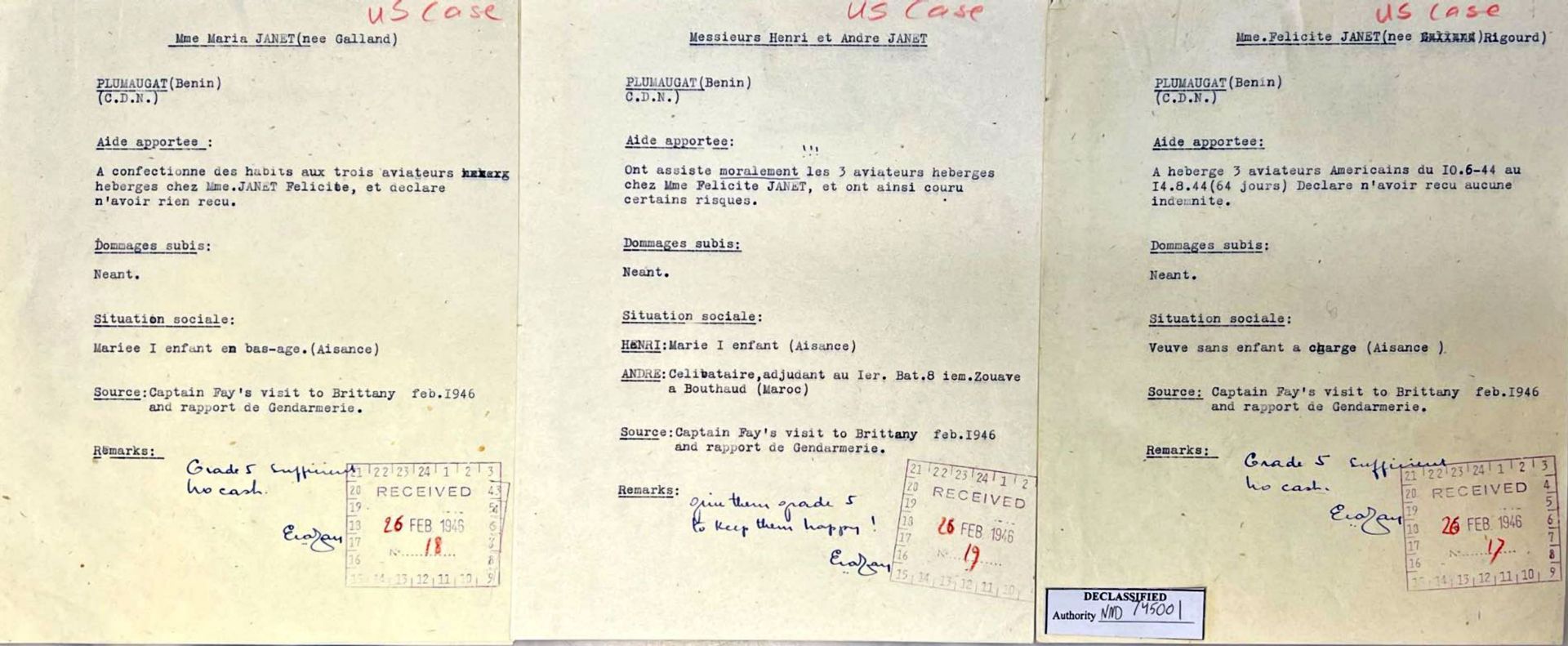

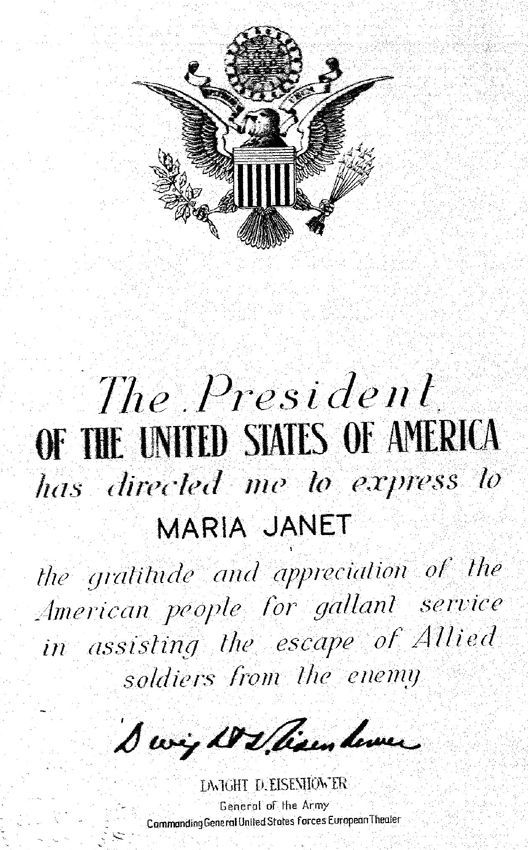

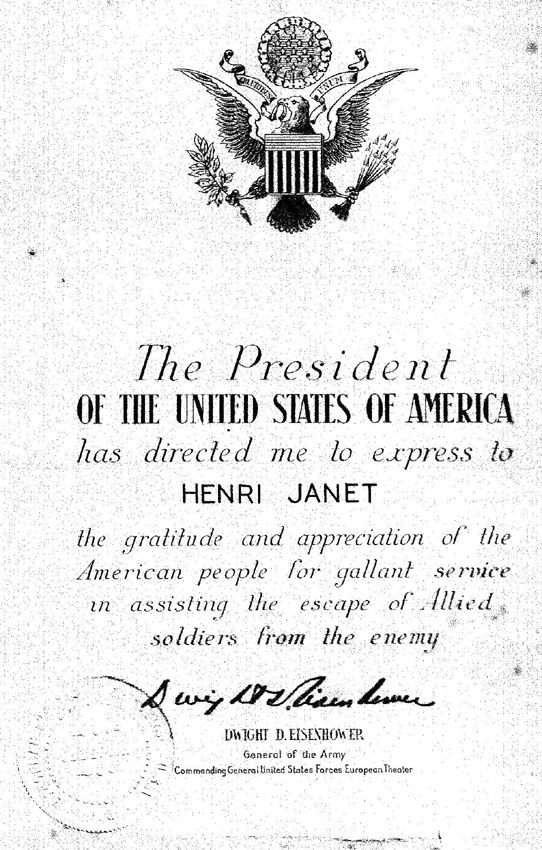

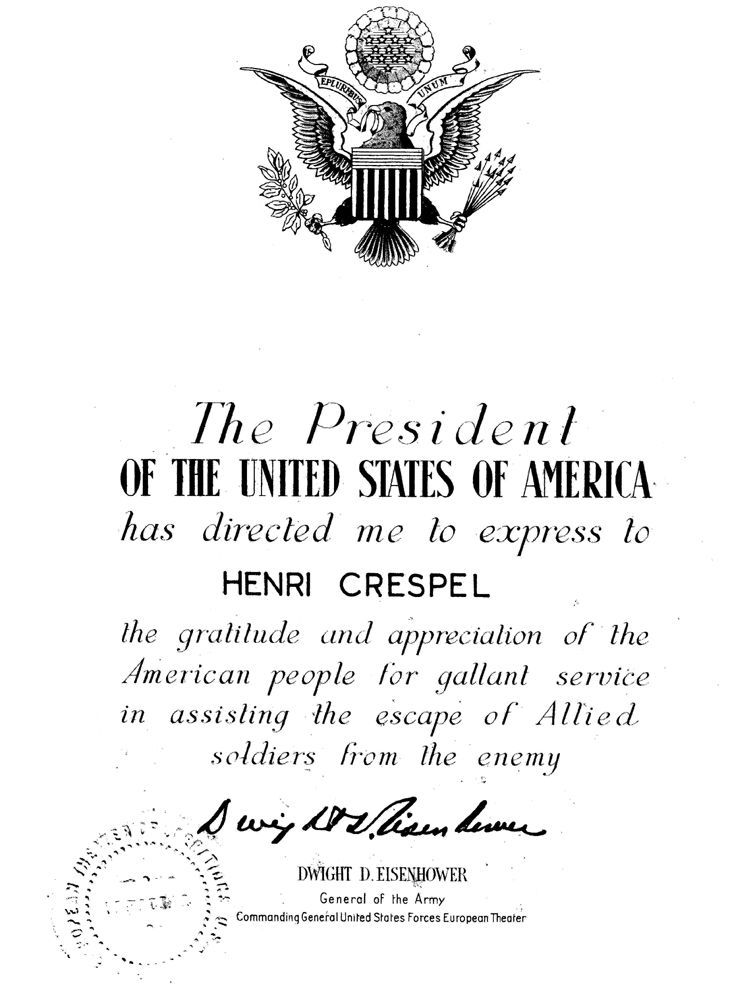

After the war, Maria and Henri Janet, as well as Henri Crespel, received certificates of recognition signed by General Eisenhower, then President of the United States of America, for the assistance they provided to American airmen (see appendices).

TESTIMONIALS

♦ Mr Crespel, from Plumaugat, Resistance fighter during the Second World War.

"When the plane crashed, we were in the village of "Queloscouet" listening to the London radio messages, waiting for a parachute drop of equipment that was planned for the following days. The airmen had jumped because we had been warned to come and see what was happening near us. We saw their white parachutes open, scattered in the sky. The plane was coming from Plumaugat and also passed over Lanrelas. It was losing a lot of altitude. Arriving above the "Breuil" bridge, it turned around and then crashed in the village of "Bodinais". Following this event, we returned to Plumaugat, picking up an airman who had landed in the village of "l'Heume". Subsequently, with Louis Gallais, Gardon and Guinde, we picked up two other members of this crew, Fischetti and Bolin. The first had landed south of the village of "Thézelais" (location of the current sports ground), Bolin had found refuge on a farm in "Saint-Maleu". We made a hiding place for them in the Plumaugat woods. Unfortunately, that same evening, we learned that many people in the region knew the Americans' hiding place. We decided to find them a new, safer hiding place. Madame Janet, who ran a café in the village of "Bénin", agreed to take charge of our three "parcels". Near her café, in a field, she had built a shelter long beforehand in anticipation of possible bombing raids. She hid the three airmen there. To make this change of hiding place, Gardon, Guinde and I went to get them around 4 a.m. What was their surprise to see us come and wake them up at that hour. What could they be thinking ? Fischetti spoke a little French. He reassured his companions and explained to them that they had to leave for another location. Reed had a sprained ankle. He had to be carried on a back. Each took turns. Then it was my turn. Only Bolin, officer and co-pilot, hadn't yet worn it. After a while, I stopped the group and explained to Bolin that now it was his turn ; officer or not, we were all in the same boat. We crossed the Rance in fifty centimeters of water and finally arrived in "Benin". Afterward, we arranged for our airmen to tour the country, by bicycle and one at a time. This way, they could discover the region and also see the remains of their plane. One Sunday, Brother Janet took the three Americans at the same time to a party near Saint-Méen-le-Grand. This outing almost ended badly because the gendarmerie arrived in the crowd to requisition men for an unloading on behalf of the Germans. Later, we learned of three airmen from this crew hidden by the Bougueneuf maquis. We decided to bring the six airmen together to help them ; they happily met at the Loziers pond, then each group returned to their usual hiding place. They stayed with us until our Liberators arrived".

♦ Mr Michel Crespel, 9 years old at the time (testimony from November 2013).

"My memories of the crash are complete. I went to the impact point very quickly and I remember that large-caliber bullets exploded around us, without frightening us ; I was nine years old. As for the rest, it is more diffuse. I was not in the confidence of the hidden "airmen". It was only at the end of their stay that we, the children, met them. They were all three dressed in costumes cut from the same fabric, which had been stolen from the Germans at St Meen le Grand".

Photos taken by Carmine T. Fischetti, from his escape report

Houses in the village of "la Chapelle Bénin"

Mrs Gardon with the three Americans Fischetti (back center), Mister Gardon (right)

in front : Mr Guinde's son and on the right Mrs Crespel

Front center, Mrs Gardon and Mr Gardon

In front on the left, Mrs Guinde and on the far right Mr Gardon (with the cap)

From left to right : Mr Guinde's son, Mr Guinde, Mr Crespel and his son

2nd Lt Harold W. BOLIN, T/Sgt Ronald Westler REED and T/Sgt Carmine T. FISCHETTI in front

and in the background from left to right Mrs Guinde, Marie Janet and her baby, Mrs Veuve Janet and Mrs Crespel

Miss Marguerite Biou, friend of Mrs Janet

Families make the "V" for victory

Miss Marie Hazard and Miss Gibauvet, from Plumaugat, friends of Mrs Janet

♦ Sergeant Thomas Senan McInerney's testimony made on December 3, 1995 on request of Mrs Digges, wife of the B-24 pilot, 2nd Lt. Thomas I. Digges.

Jean McINERNEY, wife of Thomas Senan McINERNEY, kept his photo in a locket.

Photo Deborah Sullivan (nee McInerney)

At the beginning of his testimony, Sergeant McInerney tells the return from the June 7, 1944, mission over the Normandy coast: " There were fighters all around us, I noticed that a Focke-Wulf [German fighter aircraft] had followed us over the English Channel, on the way back to our base. Our accompanying P-47s noticed this and began to circle around it. It was surrounded. All these aircrafts looked alike and had a similar silhouette. We heard gunfire. Tracer bullets streaked across the sky, but we didn't see what happened next because our base was in sight. I was very happy to put my bag on the ground. After a short sleep, we were called for a new briefing late at night. We were given our target, a bridge in Nantes. Our intelligence officer, like me, was from Jackson, Michigan. Before the war he was in charge of the news at WIBM radio. He told us : "In the sector you have to bomb today, you will face fighters but no anti-aircraft guns." It turned out that the opposite happened over Nantes, as the anti-aircraft guns hit the bomber in the nose, tail, and mid-body, and engines 1, 3, and 4. There were shells all around us, but not a single fighter was seen on target. During the briefing, he said that the French were close to the Germans, so if you arrive on the ground, don't believe them. When it happened to us a few hours later, we all thought about what he had told us and we were sad. After the briefing, we didn't have time to go to the mess, so just before takeoff, we were given sandwiches and cans of fruit juice on the runway. I dreamt of those sandwiches many times during my year of hunger. They must have burned. with my Colt 45 in the cockpit of the ''Shady Lady'' because I never saw them again after takeoff.

Jean and Thomas Senan McINERNEY were married on August 4, 1945.

Photo Deborah Sullivan (nee McInerney)

We took off and climbed in altitude and crossed the cloud layer at 12,000, 13,000 feet (3,600, 3,900 m). We searched for the aircrafts of our group but not one was found. Since we did not want to cancel our mission, we continued to search for them. We then joined another group and arrived at our objective: a bridge in Nantes. We did little damage to this bridge because our bombs did not hit it. Upon reaching the objective, the flak was so dense that we felt as if you were walking on it. We had on board bundles of ''Chaff'' [anti-radar metal ribbons] which, when thrown, split into hundreds of pieces, like Christmas tree icicles, to simulate aircrafts on German radar ; apparently, the German gunners did not believe in Christmas.... We were hit. It sounded like road gravel on a galvanized roof and we all jolted to our feet. "Hit, hit !" Smitty [Homer Lee Smith] yelled in anguish into the intercom. As it turned out, five of us were wounded. Smitty was wounded in the neck and one shoulder, and it was several weeks before he received proper medical treatment. Aboard our bomber aircraft, there was a cacophony, as pilot Tom Digges called everyone to confirm the damage. We were losing altitude and Tom Digges told us to set our parachutes just in case we had to leave the plane. I had my 45 Colt with me, which I had forgotten to turn in before takeoff. I placed it near my .50 caliber machine gun and then checked to see that my Mae West was properly positioned on me. Next, I put on my ventral parachute. Digges pressed the intercom and said, "I can't keep this son of a bitch flying." With that, I went to the tail turret and told Jack Allen to put on his parachute and to give me his seat. Jack had been assigned as a last-minute replacement for Harold Moe, who was hospitalized with pneumonia. After shaking my hand, he went to the rear hatch where a camera was installed. Next, I helped Cavestri out of the ball turret. The ball turret was electrically locked, but it could be manually operated without any problem. Tony told me he was heading forward to help drop the bombs one by one, assisted by King [Kester King], our bombardier. Then I realized that my right leg had been hit by shrapnel. Blood was seeping through my clothing above the shin ; I placed a dressing on the wound, then went back to the rear to retrieve my first aid kit and equipment. I took the opportunity to take off my flight boots and put on my army shoes. Before leaving the aircraft, I made the sign of the cross and jumped out the rear hatch. Allen had just gone ahead of me. I was supposed to count to ten, but I had to stop counting because I heard shots being fired from the ground.

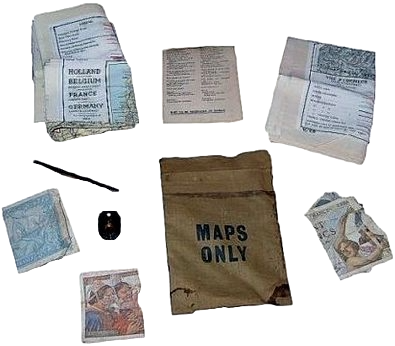

I think I was at 1200-1400 feet (about 390 meters). I immediately pulled the handle of my parachute, but as my arm was fully extended, my hand opened wide and the handle fell. I regretted it because I wanted to keep it with me as a souvenir. When the parachute opened, my crotch straps pulled my whole body upwards. I felt it even in my thyroid. I swung for a long time about four times to land in a field of grain, right at the foot of a fruit tree. Immediately I picked up my lines and my parachute, took off my life jacket to hide everything in a discreet place near this tree. I took some grains to hide the place of my fall and straightened the stalks to cover my passage in this field. It was then that I heard the farmer shouting [in French] "come on, come on, lots of Germans around here." This farmer waved at me feverishly. I walked about 30 meters, hurrying to reach this farm. As I hurried along the path, a boy about 5 or 6 years old handed me my helmet, which had fallen in the wake of our plane. It was a comfort to me to arrive at this farm. I returned the helmet to this child, telling him to keep it for him as a souvenir, but taking care to hide it immediately. I asked to take off my uniform immediately. It was 9:15 a.m. which meant 15 minutes into the jump. I was given a pancake in one hand and a glass of cider in the other. A drink I was discovering. Everything happened very quickly. Barely changed and dressed in this farmer's clothes and sitting at his table, a navy blue cap pulled down on my head, a breathless German appeared and asked "paratrooper." Lowering my head, I replied "no, paratrooper." He slammed the door as he left and said, "Thank you very much." The farmer told me, "Don't make any contacts, or you'll probably be reported." I immediately decided to leave the area, as it was risky for the farmer and his family. I began my escape by setting my compass to the north. An hour after leaving, I met a man of about 18 years old. His eyes and head told me he knew I wasn't from the region. He didn't make a friendly approach. Nothing more, not even a nod, and I continued walking along the long northern path. I had the feeling his eyes were following me until I was no longer visible. I wondered about him. Why wasn't he in uniform at his age? He wasn't the one who would have directed me to a maquis. I kept walking and came to a crossroads with road signs. I realized I was lost. After walking a few more kilometers, I took out my escape kit [photo below].

I took a break and took the opportunity to eat some sugar. I found two compasses in this kit. I felt reassured because I was indeed heading north. After walking for a long time, I arrived in a village with a large grassy square, surrounded by several houses, but no church or shop. At the end of the square, a tap with a hose for watering. I opened it and drank to quench my thirst. There was no one around me. I continued my way in this village, when I saw three people conversing with others through a window. As I passed, I inclined my head and said "hello." They inclined their heads and said "hello" to me but without starting a conversation. I continued my way still north thinking of rejoining our lines. A little later, I continued walking and reached another village, larger and more lively. I was drawn to what seemed to be a pub or a bar. I had seen it from a distance and my Irish stomach made noises. My saliva came to my lips. What hell ! I had francs in my escape kit and dollars and pounds sterling in my wallet. I was about to cross the street when a sidecar appeared and parked in front of this bar. I could see from behind a German officer whose boots were well polished. I moved quickly away. Night began to fall. I thought the Germans had instituted a curfew. As I walked along a long, curved wall, I saw three blond young men, strapped into black uniforms, as proud as peacocks, occupying the entire sidewalk. I thought, 'That's it, I'm caught.' At the last moment, the one closest to the edge moved aside to let me pass without touching me.

It began to rain as I finished crossing the village. It was getting darker and darker, the night thicker and thicker. I stopped at a farm, but the farmer didn't seem to understand that I was looking for shelter. He told me to continue. I walked to a very dense fir trees wood and began to sleep in my thin blanket under the protection of my guardian angel. I was awakened during the night when the rain found a hole in my blanket and reached my skin. I slept nevertheless until dawn, wet and cold. Since this dawn was very gray, damp, and foggy, I set off again, but not directly toward the road so as not to be seen. I walked along the wet fields for several kilometers. After a large curve, I finally reached my path, still heading north. The sun had appeared and its warm rays were drying my clothes ; I told myself that surely there was a god in heaven to receive such precious help at this moment. I had my rosary (prayer ring) with me. I began these prayers after a pater noster and then I joined the road. This rosary came from the chapel of the Little Sisters of Saint Theresa and was given to me by my Mother Mary Doherty McInerney who had faith and believed in her old country Ireland. This faith was deep within her in the beating of her heart. To use this prayer ring, one places it on one of one's index fingers and turns it notch by notch with an Ave for each notch. The eleventh was a medal of the Immaculate Conception and the next the image of Saint Theresa on one side and a rose on the other. As the sun rose, a toothache seized me. A molar had been causing me pain for several days. Unfortunately, there was no way to get treatment in this countryside. I had been walking for a long time and my feet were also causing me pain. I had several blisters. Despite this, I continued to pray. It helped me a lot. Day broke and I crossed a village with beautiful houses. I took a street lined with two-storey houses. As I walked along, I saw German soldiers at several gates. They didn't pay attention to me because they were with local girls. After crossing several neighborhoods, I saw that I was near an airfield. I saw its entrance a little further on. I understood that I couldn't turn around without attracting attention. So I continued. The sentry raised his rifle to block my path and stammered in French. In return, I did the same. He remained perplexed. Slumping my shoulders, I assumed a stupid expression, telling him, "I'm working," and I turned around, pushing my way through the dozen Germans who were in that street. I quickly returned to the main street to get away from that place.

I also suffered from itching in my groin. I had some malted milk sachets with me, which gave me energy. In this invasion zone, I hoped to find someone who would help me anyway. I made a long journey and arrived at the approach of a large town where I wanted to hide for a break as fatigue was getting to me. As it often happens, it was a town like so many others. The road signs indicated Dinard, Saint-Malo, Mont-Saint-Michel, and Dinan, the town I came from. It seemed to me that the Germans had numerous checkpoints. I discreetly reversed several times to avoid them. Then I headed towards a small bay where a group of soldiers were laying mines. I was reassured because they were busy. I could not stray far from the road. There was a checkpoint right in front of me. I had not anticipated it. It seemed empty of guards, I couldn't get away. Fifteen meters in front of me, there was an old woman. When she arrived at this barrier, two soldiers ran out of the guard post and shouted "halt! halt!" They asked her what she had in her basket and checked her papers. They beckoned me over. "Papier bitte." I trembled. "Where are your papers?" "I lost them two weeks ago," I told them. One of them turned to his superior and I heard "Oberfeldwebel" and then other words in German that I didn't understand. The latter came up behind me and shouted "marschier!" We headed towards the bay where I came from and there I was presented to a non-commissioned officer. He asked me some questions that I didn't understand. One of the soldiers saw the chain around my neck and took out my Saint Christopher medal and my identity plate. "Ah ! For you the war is over" by sticking a finger in my chest; I said that I was an American airman and that I wanted to be treated according to the Geneva Convention. He stuck his pistol deep in my stomach and if there had been no witness, he would no doubt have pulled the trigger. They took me on foot, through the town, to an artillery battery, hidden under the trees of a park. Most of the townspeople as I passed made the "V" for victory with their fingers, winked and made other friendly hand signals. But others spat on me, and laughed at me as we walked down the street before reaching the park. I was presented to a lieutenant. I had sworn to myself not to show my fear, they searched me severely, my escape kit triggered a delirium as did the photos of my friend. My wristwatch, although common in the USA, astonished them.This type of watch was not yet on sale in Europe. For at least an hour, I was treated like a curiosity. A young soldier handed me a piece of his food ration and said "essen!" (eat!), and he also gave me a carrot. I thanked him in English. More than an hour later, I was transferred to a car, guarded by three soldiers armed with a machine gun.

I was at the back between two soldiers. They led me to an airfield.[Pleurtuit?] where I underwent a tough interrogation. I was stripped completely naked, then they gave me back my underpants. For them, I was a spy and as such, I could be shot anytime. It was a very painful situation. There were some truths in what they told me. I told myself that if I had to die, it would be my choice and that under no circumstances would I grovel at their feet. I told them my name, my rank and my service number. That was enough for the application of the Geneva Convention. Needing to go to the toilet, they led me outside barefoot, walking on sharp rocks, especially since my feet had already suffered during my journey. It was a journey of great misery. As I returned, they searched my clothes. Every seam was open, even my shoes, which had their soles ripped open. They gave me back my clothes as they were and took me outside where a truck was waiting for me. My hands were tied behind my back with electric wire. They made me sit on a platform facing the road, and tied my wrists to the side of the truck. Every bump in the road twisted my arms and shoulders. For several hours we drove like this. The rain began to fall and it continued all night. Since I was completely wet, they put a tarp over me. A while later, the truck stopped and they helped someone get in. He was immediately protected from the rain by a tarp. A hole in the road traumatized my arm, I screamed in pain because it hurt so much. Imagine my surprise to recognize the one they had put in the back of the truck. "Tony, is that you? I'm Homer Lee Smith." This reunion was a happy moment. Finally, I was no longer alone. We could converse discreetly.

The truck drove until midnight in the pouring rain and finally stopped at an outpost. They made Smitty get out. Then it was my turn. Everyone went back with Smitty except one who was guarding me. He untied me from the side rail but not my wrists. I don't know how I got to the ground. I had the misfortune to smile at my guard when he hit me in the face with a rifle butt, injuring my nose. God, he hurt me, but I didn't want to give him the satisfaction of falling at his feet. Then, when his comrades asked me what had happened to me, he himself replied that I had fallen while jumping. They put me in a room and didn't remove my restraints. I had trouble sleeping tied up like that. A Frenchman came during the night. He spoke English. He was drunk. He promised to come back and free me. I never saw him again. The next morning, a German officer who spoke English approached me and untied me. I lost feeling in my arms. They remained numb for weeks; 50 years later, my right shoulder still hurts. My nose was reattached by a surgeon in 1946, and my jaw a few years later. In the morning, Smitty and I left the area in two separate trucks. We headed south from the coast to the road that led us to our captivity. Each truck had a machine gun on a tripod. When an airplane appeared, we stopped, and the machine gun would fire wildly. I couldn't escape because the guards were close by. During attacks, they hid in roadside ditches. I had to join them. It was dangerous, but sometimes fun when one of their airmen made a mistake and fired at them. Once, they screamed. I didn't have time to jump out of the truck. I came to take refuge under the machine-gun post. I thought I had been hit by the shots. At the end of the attack, I went out and realized that I had been burned by the burning casings of the shells fired by that truck. We passed near the town of Sablé, from where, after a long journey, I reached my prisoner-of-war camp in Germany.

The truck drove until midnight in the pouring rain and finally stopped at an outpost. They made Smitty get out. Then it was my turn. Everyone went back with Smitty except one who was guarding me. He untied me from the side rail but not my wrists. I don't know how I got to the ground. I had the misfortune to smile at my guard when he hit me in the face with a rifle butt, injuring my nose. God, he hurt me, but I didn't want to give him the satisfaction of falling at his feet. Then, when his comrades asked me what had happened to me, he himself replied that I had fallen while jumping. They put me in a room and didn't remove my restraints. I had trouble sleeping tied up like that. A Frenchman came during the night. He spoke English. He was drunk. He promised to come back and free me. I never saw him again. The next morning, a German officer who spoke English approached me and untied me. I was'nt feeling my arms. They remained numb for weeks ; 50 years later, my right shoulder still hurts. My nose was reattached by a surgeon in 1946, and my jaw a few years later. In the morning, Smitty and I left the area in two separate trucks. We headed south from the coast to the road that led us to our captivity. Each truck had a machine gun on a tripod. When an aircraft appeared, we stopped, and the machine gun fired wildly. I couldn't escape because the guards were close by. During attacks, they hid in roadside ditches. I had to join them. It was dangerous, but sometimes fun when one of their airmen made a mistake and fired at them. Once, they screamed. I didn't have time to jump out of the truck. I came to take refuge under the machine-gun post. I thought I had been hit by the shots. At the end of the attack, I went out and realized that I had been burned by the burning casings of the shells fired by that truck. We passed near the town of Sablé, from where, after a long journey, I reached my prisoner-of-war camp in Germany.

♦ 2nd Lt Bernard Koller dit "Barney" (Escape & Evasion report E&E 1449 dated September 3, 1944).

Koller was the navigator of the "Flying Fortress" [if the term "Flying Fortress" is commonly attributed to the Boeing B-17, it was also sometimes attributed to the Consolidated B-24] which crashed at "La Bodinais" in Lanrelas on June 8, 1944

" I went to bed at 11 p.m. and was woken up at 1 a.m. to go eat. The briefing (instructions) took place as usual. Early in the morning, we were gathered around the "Shady Lady" [see the anecdote about the aircraft's name at the top of this page], waiting for the engines to start. Part of the sky was starry, but the fog was coming towards us. As usual, I checked all my equipment, but also my oxygen supply, then my flight suit and my flak vest. We finally took off to climb heavily to 12,000 feet (3,600 m). As navigator for this crew, I started looking for other "Fortresses" that had already left before us to gather. I didn't see a single one. We circled endlessly like bees around a hive. After a very long time, we hooked up with another group. Then we headed for the English Channel. I saw hundreds of aircrafts from one end of the sky to the other in a huge formation like a large square. Everything went according to plan until we reached the target. The bombardier pushed the bomb release handle but they didn't fall. He also pressed the emergency circuit but without result. He immediately called our pilot, "Tommy," who told him to fire again on this circuit; but impossible, the bombs were still on board. "Tommy" asked me if there were other possible targets on the way back. I began to look at my charts when a terrible "boom" invaded the aircraft. It sounded like someone had thrown a large rock at some tin cans and then suddenly over the intercom "I'm hit, I'm hit." I looked at the bombardier, it wasn't him who had been hit. We were losing altitude. I opened the door of the front turret and saw that "Smitty" had been hit, but I didn't know how seriously he was injured. He had blood on one side of his face but seemed more scared than hurt. I understood his fear. "Tommy" told us to put on our parachutes in case we needed them.

I tried to call our little brothers for help (the other aircrafts). The bombardier, 2nd Lieutenant King, went back to try to get rid of the bombs. I thought we wouldn't be able to fly back across the Channel because of the headwind and the distance to the coast. I helped "Smitty" put on his parachute and went back to the drop hatches to see if I could be of any help. "Tommy" then ordered us to bail out. Carmine was sure we could get back in. It was "Tommy" who knew the condition of the aircraft best and who had told us to bail out. I told "Carmino" to be quiet and bail out. I was the sixth to leave the aircraft. When my parachute opened, I noticed other open parachutes around me but at a distance. Suddenly, I saw the B-24 turn to the right and come right back toward me. I felt helpless. I thought it was a stupid way to die, crushed by your own plane. The bomber turned again right in front of me and crashed with a terrible explosion. A great column of black, oily smoke rose from where the aircraft had come down. I saw people watching me go down. They were in a sort of fenced-in farmhouse, which is quite typical of French farms. I also noticed a wooded area where I could take refuge. I felt relieved as I fell into a plowed field. A big shock on landing, but I quickly recovered. I threw off my parachute harness and life jacket. Halfway across, I hid them in a ditch. I started running across a field and saw a man also running. Having seen him first gave me the advantage. I hid behind a tree and decided to watch him. He looked decent. So I called him, and he shook my hand. He couldn't say a word; he didn't seem very smart to me, so I decided to flee as quickly as possible. I moved away from the scene of the accident, toward the wooded area I had noticed during my descent.

Il était plus de 9 heures. Je me débarrassai de mes lourdes bottes de vol pour pouvoir courir plus vite. Je traversai une route empierrée et crus que des gens m'avaient vu pénétrer dans le bois. Je courus encore une demi heure et il me fallut faire une pause. Je m’assis et fis l'inventaire de ce que j'avais. Je me débarrassai de mon couteau de poche au Manche incrusté de nacre. On m'avait dit que des aviateurs avaient été fusillés comme espions pour avoir possédé sur eux des couteaux, si petits fussent-ils. J'avais mon trousseau de prisonnier de guerre, une carte de France et d'Espagne ainsi que 2 000 francs. Je restai allongé, attendant calmement que quelqu'un s'approche. J'entendis des oiseaux chanter et voler et à chaque bruit, j'imaginai que quelqu'un était derrière moi. Je restai en place jusqu'à 17 heures, puis je décidai d'explorer les environs et de me diriger vers le Sud-Est. Finalement je sortis du bois, vis la flèche d'une église et décidai de contourner le village. J'étais très méfiant,évitant tout le monde au début . Je vis un homme et son fils qui binaient des choux dans un champ. Je décidai de leur demander un verre d'eau. Je ne savais pas un seul mot de Français, il me fallut utiliser le langage des signes pour me faire comprendre. Le fils rentra chez lui et apporta du cidre. Le père dit au fils de me donner des vêtements civils que je pris en échange de ma combinaison de vol. Il me dit de le suivre à la maison, où sa femme me donna du pain. Tout à coup, sa femme, qui observait par la fenêtre, dit quelque chose à son mari. Il me prit par la main et je le suivis dans une grange pour ensuite franchir une clôture sur l’arrière de la ferme. Je crus que la police allemande me poursuivait déjà. Je courus en un grand demi-cercle autour de la ferme et pris l'orientation du sud. A la ferme, la fermière m'avait montré un mouchoir avec les initiales H.W.B. (Second lieutenant Harold W. Bolin) inscrites dessus, si bien que je sus que le copilote était en sécurité et m'avait précédé. Je ne vis aucune autre trace d'autres membres de notre équipage. J'évitai tout le monde et marchai jusqu'à 22 heures. Ce soir là, je décidai de dormir dans un fossé sous un arbre. Il se mit à pleuvoir et il plut toute la nuit. L'arbre m'abrita un certain temps. Il commençait à faire froid. Je pensai à me rendre car au moins je serais au chaud quelque part et j'aurais à manger. Vers 4 heures du matin, je décidai de marcher pour conserver ma chaleur. Il faisait encore nuit noire. Malgré tout, je restai dans les champs, dissimulé. Je marchai jusqu'à environ 10 heures et m’arrêtai dans une ferme où je demandai à une femme si je pouvais dormir dans la grange. Elle me dit ''d'accord'' ; je dormis environ une heure quand arriva un homme qui me fit signe de prendre la route. Je marchai jusqu'à 18 heures et m’arrêtai pour demander quelque chose à manger. Une femme m'apporta quelque chose qui ressemblait à un torchon de mailles verdâtres et sale. Il y avait du beurre dessus. Ça avait le goût de ce à quoi cela ressemblait. Elle me donna aussi du cidre. J'appris plus tard que cette nourriture particulière était un grand régal là-bas, et était faite de galettes aux œufs. J'ai ensuite marché jusqu'au soir,et décida de dormir encore dans un fossé. Pluie, pluie, pluie toujours et il faisait très froid. J'étais résolu à me glisser sous la première meule de paille que je rencontrerai par la suite pour récupérer un peu. Ce que je fis jusqu'à l'aube et ensuite je repris ma marche vers le sud. Arrêt pour chercher à manger. Une dame me donna du pain. Elle me dit de ne pas aller par là, elle me faisait les gestes d'un tireur. Je décidai pourtant de partir dans cette direction. J'avais toujours froid. J'étais trempé et très fatigué. Je n'avais dormi que deux heures ces trois derniers jours. Je repris la route, les champs étant trop mouillés. J'arrivai à un virage et vis une sentinelle allemande en face d'un immeuble avec son fusil à l'épaule. Mon cœur se serra. Elle me vit et donc pour ne pas attirer son attention, il me fallut continuer à marcher vers elle. Je passai devant ce soldat. Il ne se douta de rien. Dans l'immeuble en face, d'autres allemands, dans un bureau, téléphonaient. Je pris la première route sur ma droite pour sortir de là au plus vite. Je vis trois autres allemands en vélo, apparemment en patrouille. Je passai devant eux. Je pris la route suivante et encore une autre à gauche, pour sortir de la ville. Je vis deux Allemands debout, prés de deux tentes individuelles vertes, allumant leurs cigarettes. Mon cœur battait si fort que je pensais qu'ils l'entendraient à quelques mètres de distance. Je quittai enfin la ville, très fatigué. Je cherchai un lieu pour passer la nuit au sec. Je vis une soue à cochon vide, mais je préférai voir avant les fermiers. Je m'assis dans un fossé en attendant qu'ils rentrent à leur ferme. Rentrant, ils se dirigèrent vers moi. Ils avaient un chien. Je préférai reprendre ma route. Plus loin, je vis un homme et son fils qui labouraient leur champ. Je leur demandai à manger. Ils m’emmenèrent chez eux et me donnèrent de la soupe de pain. Elle était très bonne. Ils avaient un foyer chaud, et ils descendirent un lit du grenier et me dirent de dormir dans leur cuisine. Extrêmement fatigué, je m'endormis aussitôt.

Le lendemain matin, je leur demandai un miroir pour me raser. C'était un dimanche et le fermier me dit qu'il devait se rendre à la messe. Je m'en allai. Je ne faisais confiance à personne. Je continuai mon chemin vers le sud pendant un certain temps. Une patrouille allemande camouflée de branchages me dépassa. J'aurais bien aimé être en voiture, mais surtout pas avec eux. J'étais fatigué par cette longue marche à pied. Des tas de gens marchaient le dimanche, aussi je restai sur de petits chemins faisant en sorte de ne rencontrer personne. Ce jour là, j'ai marché jusqu'à la tombée de la nuit. Je demandai un peu de nourriture dans une maison. L'homme me donna du pain. Je lui demandai si je pouvais dormir dans sa grange. Il me dit oui et me donna une couverture. Vers 23 heures, il vint me chercher et me dit de venir dans sa maison. Il me donna à manger une soupe de pain et de lait, très bonne. Il me dit qu'il était dans la DCA Française jusqu'en 1940. Il avait travaillé en Allemagne mais il avait plus de 40 ans, alors il avait été libéré. Son beau-frère était prisonnier en Allemagne depuis 3 ans. Il me donna un petit déjeuner le lendemain matin. Je traversai un champ, quand soudain un Messerschmitt 109 passa au dessus de moi, très bas. J'aperçus le pilote dans son cockpit. Ensuite je traversai une forêt toute la journée ; le soir, je recherchai où loger pour la nuit. Un homme m'indiqua une grange. Je grimpai à une échelle quand soudain, un autre homme me dit de déguerpir. Je demandai à un autre fermier. Il me dit non. Je marchai encore et encore et je vis dans la pénombre un homme auquel je demandai de dormir dans une meule de foin. Il m'accorda cette autorisation. Il faisait très froid. J'étais fatigué et affamé. Je me levai à l'aube et repris ma route, toujours au sud, j'avais des ampoules aux pieds qui me faisaient souffrir. Le soleil se montra enfin mais je me trouvai déprimé, me demandant combien cela durerait encore. En soirée, je demandai à un homme un peu de nourriture. Il me donna de la soupe de pois où l'on retrouvait tout, même les cosses. Cet homme me dit que les Allemands étaient à 3 km. Il avait peur de me laisser dormir dans sa grange. Il finit par accepter. Les chevaux de l'écurie voisine s’agitèrent toute la nuit me rendant un sommeil difficile. Je parti au matin et je continuai mon parcours jusqu'à 3 heures de l’après midi. Je cherchai de la nourriture. Une femme, qui ressemblait à Jeanne Burton, me donna une omelette, très bonne. Elle me donna du pain et mit un œuf dans ma poche. Arrivé près de la Loire, je trouvais le fleuve très grand. Ne sachant pas nager, il n'était pas question de le traverser ainsi. Je décidai de traverser en passant sur un pont. J'arrivai dans une petite ville où je rejoignis un autre bras du fleuve. Le pont avait été détruit par les bombes. Mon cœur se serra. Sorti de la ville, je m'assis sur la rive. J'étais très abattu. Je vis un homme qui remontait le fleuve dans une barque. Je l'appelai. Il me fit traverser. Je me dis que j'avais eu de la chance.

La nuit suivante, je dormis dans une grange. Je mis ma veste sur ma tête pour ne pas avoir de foin sur moi. J'avais un orteil infecté à cause de mes ampoules. La journée suivante je marchai toute la journée malgré mes douleurs aux pieds. J’aperçus un barrage de ballons au dessus d'une ville industrielle. Le soir, une dame aimable me fit une omelette de 6 œufs. Affamé je lui en redemandais. Elle accepta et m'en refit une autre. Elle dut penser que j'étais un goinfre. A ce stade, je me posais la question de savoir s'il existait un réseau d'aide aux aviateurs évadés. Comment avais je donc été si longtemps sans contacter personne. Il me fallait continuer à marcher. Pas d'autre solution. Je traversai une ville et je vis un soldat en vélo qui s’arrêtait devant un magasin. Il mit son casque sur la selle. Je passai prés du vélo et je fus tenté de le balancer puis de m'enfuir, rien que pour rire. Mais je n'aurais peut être pas rit bien longtemps. Je me demandai comment ils pouvaient faire pour ne pas me reconnaître. Je pris la direction du sud-est. Il me fallut me reposer souvent. Voila plusieurs jours que mon évasion avait commencé. Mes jambes devenaient terriblement raides. J'aime bien voyager mais pas sur un aussi long chemin. Une dame me donna du pain et du fromage moisi. J'avais détesté. Je vis des avions P-47 qui bombardaient à l'horizon. Sans doute un train. Ça me plaisait beaucoup de les voir voler par ici. Ça me donnait le sentiment que ça vaut le coup de continuer la lutte. Marche. Marche. Marche. Je suis ensuite passé devant un hôpital couvert de croix rouges partout. Il y avait des tourelles antiaériennes de chaque côté. De cet hôpital sortirent des camions chargés de soldats. Il y avait aussi des femmes. Qu'est ce que ces femmes faisaient sur ces camions ? Elles n'avaient pas d'uniformes. Je descendis une côte et pris ensuite un grand virage. Des gens attendaient qu'un train passe au passage à niveau. Ils me virent. Il fallait que je traverse absolument. Malgré tout, j'attendis que ce train militaire soit passé. Les soldats allemands avaient l'air très fatigués. Ils étaient assis sur des bottes de paille, dans des wagons de marchandises aux portes ouvertes. La plupart blonds et jeunes. Ils avaient un équipement parfait. Simplement un tas de jeunes idiots en route vers la mort. Pourquoi continuent t'ils à se battre alors qu'ils savent bien qu'il vont prendre une sacrée raclée. Mais savent t'ils seulement qu'ils sont déjà perdants. Quelle connerie que cette guerre. Des Français les saluaient de la main. Je leur fis signe aussi. S'ils savaient qu'un Américain les saluait. Quelle farce peut être la vie parfois...

Après avoir marché encore 14 jours, de l'aube au crépuscule, je souhaitai me poser un peu dans une ferme et aussi trouver à manger. J'avais déjà parcouru 400 km depuis mon arrivée sur le sol Français. J'y ajouterai plusieurs dizaines de kilomètres en plus, vu le nombre de contournements des villes où j'étais passé. Une jeune femme me dit quelle devait demander la permission pour me donner à manger. Elle demanda à sa grand-mère qui répondit positivement. J'attendis, puis je pus manger de la soupe dans cette famille. Un foyer Français typique. Tout le monde parlait à la fois en faisant tous ''gloup''. On jetait des morceaux par terre pour les chiens et les chats. Le pain se présente en grandes miches rondes de 4 kg. Tout le monde à son couteau et se coupe une tranche. Une jeune femme était muette mais de temps en temps poussait des cris qui me donnaient la chair de poule. Une autre n’arrêtait pas de jacasser. Huguette, la première femme à qui je m'adressai, me dit de passer la nuit chez eux et que le lendemain, son père irait chercher un Anglais et un Français qui étaient censés être mes ''camarades''. Je passai la nuit là, et le lendemain, je restai planté là jusqu'à la fin de l’après midi. Un camion arriva dans la cour avec à son bord plusieurs Français qui venaient me chercher. Je croyais enfin que l'on allait me faire passer en Espagne. J'avais trouvé la résistance. Tout irait bien à présent. Soudain les Français braquèrent leur mitraillette et leurs pistolets en direction d'une voiture qui arrivait sur le chemin de la ferme. Je pensais que c'était une voiture Allemande. Mais non, ce n'était que le boucher. Après son départ tout le monde était soulagé ; l’arrière du camion était recouvert d'une bâche sous laquelle tout le monde se cachait. L’anglais s'appelait Mike, et il avait l'air très craintif. C'était un petit bonhomme maigrichon. Les Français aussi avaient peur. Nous roulâmes longtemps et lorsque nous nous arrêtâmes, nous étions au cœur d'une forêt. Je descendis du camion et à ma surprise, je rencontrai deux Américains. Ils me demandèrent quand j'avais été abattu ; je leur répondis le 8 juin. Et vous. Quand ? Le 5 mars. Je commençai à me rendre compte qu'il ne serait pas facile de sortir de France et de rejoindre l’Angleterre.

Donc Jack, Norman, Mike (448th BG/715th BS - B-24 s/n 42-100430). S/Sgt Jack M. Garrett, S/Sgt Norman C. Benson) et moi parlions la même langue, çà me faisait plaisir de les voir. J’étais très fatigué de parler avec juste deux mots de Français et de terminer la conversation avec mes mains. Nous serrâmes tous la main des Français. Norm et Jack venaient de rejoindre le groupe en même temps que moi. Le chef de ce petit groupe de résistants s'appelait René. C'était un gars de petite taille, à moitié chauve et trapu. Il ne savait pas un traître mot d’Anglais. Il y avait aussi Emile, qui avait été maire d'une ville importante dans les environs et qui faisait partie de la résistance depuis le début. Il avait fait passer les Pyrénées à 18 américains, mais il nous dit que c'était très dangereux, surtout que depuis mai, les Allemands avaient triplé leurs gardes. C’était compréhensible et nous nous résolûmes d'attendre. Il nous dit que les Allemands fusillaient les Français et que les aviateurs Américains étaient envoyés dans des camps en Allemagne, mais parfois aussi étaient passés par les armes. Emile parlait Anglais avec un accent. Il avait étudié à Cambridge. Puis il y avait Jacky, un brave type, très grand, bien bâti, très nerveux, fumeur invétéré. Plus tard, il me dit qu'il s’installerait en Amérique comme fermier. Son père était fermier et donc c'était sa vocation aussi à cause du manque de possibilités dans son pays. Je lui dit qu’il y avait beaucoup de Français au Québec et à la Nouvelle Orléans. Il y avait aussi Max. C’était un sergent de l'armée française. Il s'était évadé d'un camp de concentration. Il était gai et très athlétique. Ses connaissances en Anglais se résumaient à ''Get up, Shut up, Al Capone, Chicago''. Pierre était un jeune homme sérieux d'environ 18 ans. Un jour, lui et moi attrapâmes des visiteurs trop curieux alors que nous ramassions du bois. René les interrogea puis les relâcha le lendemain. Le premier soir de notre arrivée, Emile nous demanda si nous voulions voir sauter un train. Nous répondîmes d’accord. Nous nous installèrent dans la Citroën Traction Avant, les autres dans des camions. Au lieu de passer en Espagne avec le réseau clandestin nous voilà avec une bande de saboteurs. Quelle vie !

Ils donnèrent à Norm, Jack et moi une mitraillette Sten. Les balles sont un peu plus petites que le calibre 45 et le chargeur contient 28 balles. Nous étions censés protéger René, tandis qu'il installait le fil entre la dynamo et les pains de dynamite. Ils s'étaient arrangés pour avoir les horaires du train. Une locomotive arriva seule en haletant. Elle était sur la mauvaise voie. Il faisait nuit noire. Nous étions tous allongés derrière un petit talus, attendant le train. Nous entendîmes tout d'un coup des moteurs d’avions. Un avion passa au dessus de nous et lança des fusées jaunes. C’était un avertissement pour que les gens de la ville proche se sauvent au plus vite. Cet avion revint et cette fois-ci lâcha des fusées blanches. Le reste des avions arriva et lâcha ses bombes. La terre tremblait et grondait. Les avions s'en allèrent et tout redevint calme. Nous attendîmes longtemps. Il faisait très froid. Enfin le train arriva, mais le détonateur ne fonctionna pas, si bien que rien ne se produisit. Après, j'eus une grande peur, ne sachant ce qui allait suivre. Nous rentrâmes à toute vitesse par des chemins détournés. La traction tomba en panne. Quelle tuile ! Si les Allemands empruntaient cette route, nous pouvions dire adieu au monde. Le camion nous remorqua jusqu'au camp. Les résistants dormaient le jour et opéraient la nuit. Ils ne voulurent pas de nous pour la mission suivante. Un gendarme arriva au camp. Il s'appelait Robert et venait de la ville voisine où il était chargé de la garde à la prison. Il vint donner le double des clés de cette prison au groupe de résistants. Ce groupe, dans les jours suivants, libéra ainsi plus de 400 prisonniers politiques. Les prisonniers eurent peur de sortir au début de l'intervention car ils pensèrent à un piège. Ils pensaient que les Allemands les abattraient tous. Deux soirées plus tard nous avons déménagé dans une autre forêt. Il fallait changer souvent d'endroit pour que nous ne soyons repérés. L'abri des maquisards était fait de tentes coupées dans de la toile de parachute. Ils ne séjournaient jamais dans des maisons car, en cas d'attaque, ils ne pourraient se sauver. Dans les bois ce serait plus facile de s'éparpiller et disparaître. Mike, Norm, Jack et moi dormions sous la même tente. Nous avions une couverture dessus et une en dessous. Mike était très nerveux et la nuit, il allumait une cigarette toute les demi-heures. Jack avait des démangeaisons et il se grattait comme un chien qui a des puces. En cas d'alerte nous devions nous enfuir à travers bois. Le signal était deux coups de feu. Nous dormions tout habillé pour conserver la chaleur le plus possible et être prêt au cas où il faudrait fuir. Il n'y avait pas assez d'armes pour tout le monde.

Un soir, on fit une ronde de surveillance dans la forêt ; nous étions les 3 américains plus le cuisinier. N'ayant rien remarqué, nous rentrâmes au camp. Il pleuvait beaucoup, nous étions trempés, et il faisait très froid. La pluie traversait nos tentes improvisées. Un jour, ils tuèrent un mouton. Il fallait bien manger. Nous eûmes du ragoût jusqu'à épuisement. Un soir, vers 8 heures 30, Emile nous dit que nous allions faire un coup de main. Il nous dit qu'il y aurait du danger. Il nous dit que nous devions être prêt à tout. On me donna un vieux fusil de l'Armée Française. Il était sale et rouillé et ne pouvait contenir qu'une seule balle dans son magasin. Jack avait une Sten. Nous avions roulé jusqu'à minuit, puis on descendit du camion. Silencieusement on approcha d'un pont routier qui enjambait une voie ferrée. Nous descendîmes en bas de ce pont quand soudain, un chien se mit à aboyer. Nous avons pensé à une patrouille allemande. Norm et moi nous devions nous asseoir de chaque côté de ce pont, interdisant son accès. La consigne était de descendre toute personne qui se présenterait. J’étais assis sur le rebord droit de ce pont. J’essayais de voir de l'autre côté et aussi vers l’horizon où je distinguais des talus. Chaque fois qu'une brindille bougeait, je croyais qu'une patrouille ennemie arrivait ; je crois que ces minutes furent les plus dures de ma vie. Il faisait bien noir sous les nuages avec un clair de lune de temps en temps. Toujours l'attente sur le qui vive. Les autres gars installaient le plastic sur les voies. Nous devions attendre jusqu'à 5 heures. Si aucun train n'arrivait, nous devions faire sauter les rails. Après avoir attendu une bonne demi-heure, on entendit au loin un train qui venait vers nous. Il lança un coup de sifflet. Il approcha de nous, la locomotive soufflait et haletait comme si elle tirait un lourd chargement. On voyait sa lanterne. Je courus me jeter derrière un remblais. Je venais tout juste de me mettre à plat ventre qu'une terrible explosion se fit entendre.

Une flamme immense se projeta en l’air. La chaudière avait dû éclater. La locomotive avait déraillé et les deux premiers wagons étaient en pièces détachées. On entendait des morceaux métalliques qui retombaient sur le sol. Le remblais nous protégeait. Nous sautâmes vite dans le camion et partîmes tous feux éteints. Nous étions sur nos gardes à chaque petit village que nous traversions au cas où les allemands auraient barré les routes. Le gars à l'avant du camion avait des grenades toutes prêtes. Au loin derrière, nous aperçûmes les phares d'une voiture. Nous avons pensé aux allemands, ce qui était sans doute le cas. On réussit à les semer malgré l'absence de phares allumés sur notre camion. Nous suivions les routes de l’arrière pays pour éviter de mauvaises rencontres. Mais... enfin nous arrivâmes au camp. Un café et un peu de pain, puis direction le tas de foin proche qui nous servait de lit. Le lendemain nous essayâmes nos armes et mon vieux fusil. On tirait sur une cible placée de l'autre côté du vallon, la moitié des balles ne partaient pas. J’imagine la situation car hier nous avions les mêmes armes et les mêmes cartouches. Si l'ennemi avait engagé le combat. C’est encore le destin qui dirige cela dans nos vies. Deux jours plus tard, on se joignit à un autre groupe de maquisards. Le commandant s'appelait Jacques, René était son adjoint. Le camp était divisé en deux groupes. Nous, les Américains, nous étions avec Jacques. On reçut un nouveau cuisinier, Robert ; c'était un homme brave et qui ne rechignait pas aux tâches les plus dures. Il se promenait avec sa mitraillette au milieu de la rue, visible comme la Lady Godiva. Nous, les Américains, nous avions le réflexe simple de nous protéger de tirs éventuels. Il se disait qu'il était mercenaire auparavant. Il avait reçu une balle dans l'épaule. Il lui manquait un doigt ; il nous disait que c'était une balle qui le lui avait enlevé. Sa femme, que nous avions rencontré, nous avait dit qu'il avait été sectionné par une faucheuse. Il avait un tatouage sur le dos. Un Senor et sa Senorita. Sans doute un trophée du temps passé.

Notre nouveau commandant était excellent ; Jacques était ancien officier artilleur de l'Armée Française. Il s'était évadé d'une geôle Allemande, était passé en Espagne où, arrêté, il passa 16 mois en prison. Il regagna finalement l'Angleterre où on le forma au sabotage. Il fût de nouveau parachuté sur la France. Ensuite j'ai rencontré le ''Toubib'', un étudiant en médecine qui avait interrompu ses études du fait de la guerre. Il fut reconnu par nous tous comme médecin du groupe. C'était un gars très intelligent. Cela faisait plus de 45 jours que j'étais en France et je n'avais pas pu obtenir de brosse à dents. Le toubib m'en procura une. Il y avait aussi Antoine, toujours en train de blaguer. Il faisait tout ce qu'il pouvait pour nous. On installa notre nouveau campement au pied d'un ravin où coulait une source ; il y avait aussi un lac à une centaine de mètres de nous. Nous allions nous y baigner. J’ai toujours le souvenir de notre première nuit en ce lieu ; il plut pendant 10 heures sans arrêt. Nous n'avions plus le moral. Un jour, j'étais parti avec Mike chercher du bois. Soudain, il poussa un cri et mis la main sur sa poitrine en s’écroulant sur le sol. Il faisait une crise cardiaque. Il avait du mal à respirer. Je courus chercher René et le toubib. On le mis dans une couverture pour le transporter et il fût dirigé vers un hôpital clandestin dans un coma profond. Mike était Anglais et officier de la marine de Commerce. En 1942 il fut rescapé d'un naufrage devant Dieppe. Récupéré par des pêcheurs Français, il fut remis aux Allemands qui le mirent en prison à Cologne. Il s'évada et rejoignit la France après mille péripéties où il rencontra le groupe de résistants. Mike avait 42 ans mais il en faisait 60 ; il revint avec nous après plus d'une semaine de soin. Le médecin lui dit qu'il ne fallait plus boire d'alcool ni fumer. Mais il ne compris rien.