- Accueil

- Base de données

- 22

- USAAF

- 8th March 1943

8th March 1943

Boeing B-17F-20-BO (s/n 41-24514 code BO-R)

Plouguenast (22)

(contributors : Philippe Dufrasne, Vincent Sevellec, Jean-Michel Martin, Daniel Dahiot)

Color profile © Jean-Marie Guillou

Crew (306th BG, 368th BS) :

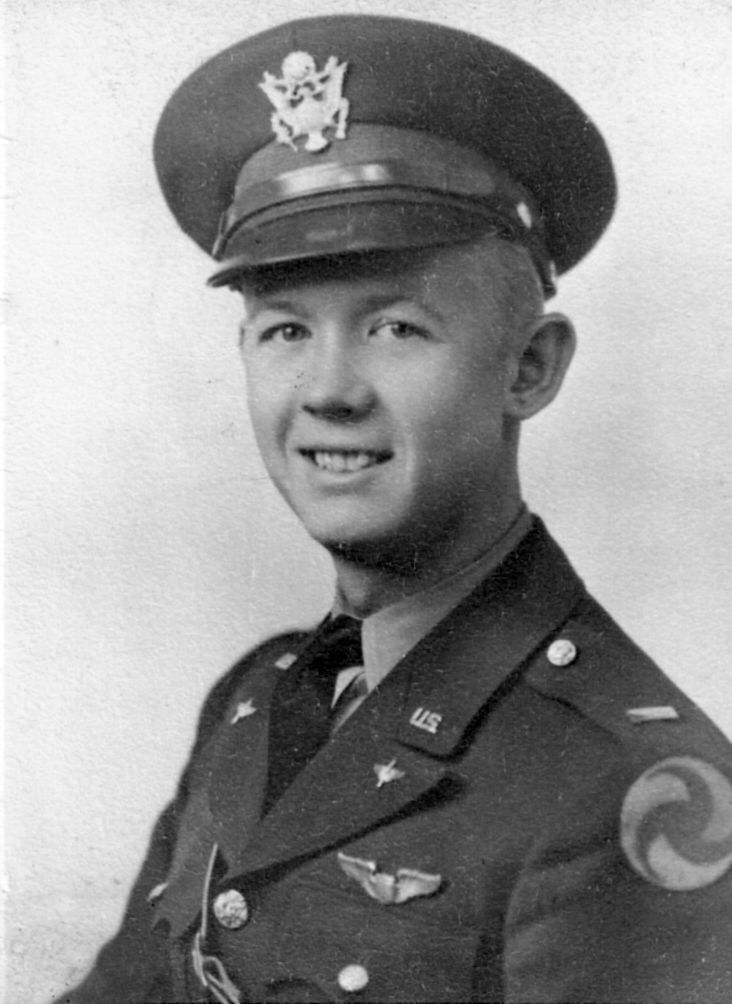

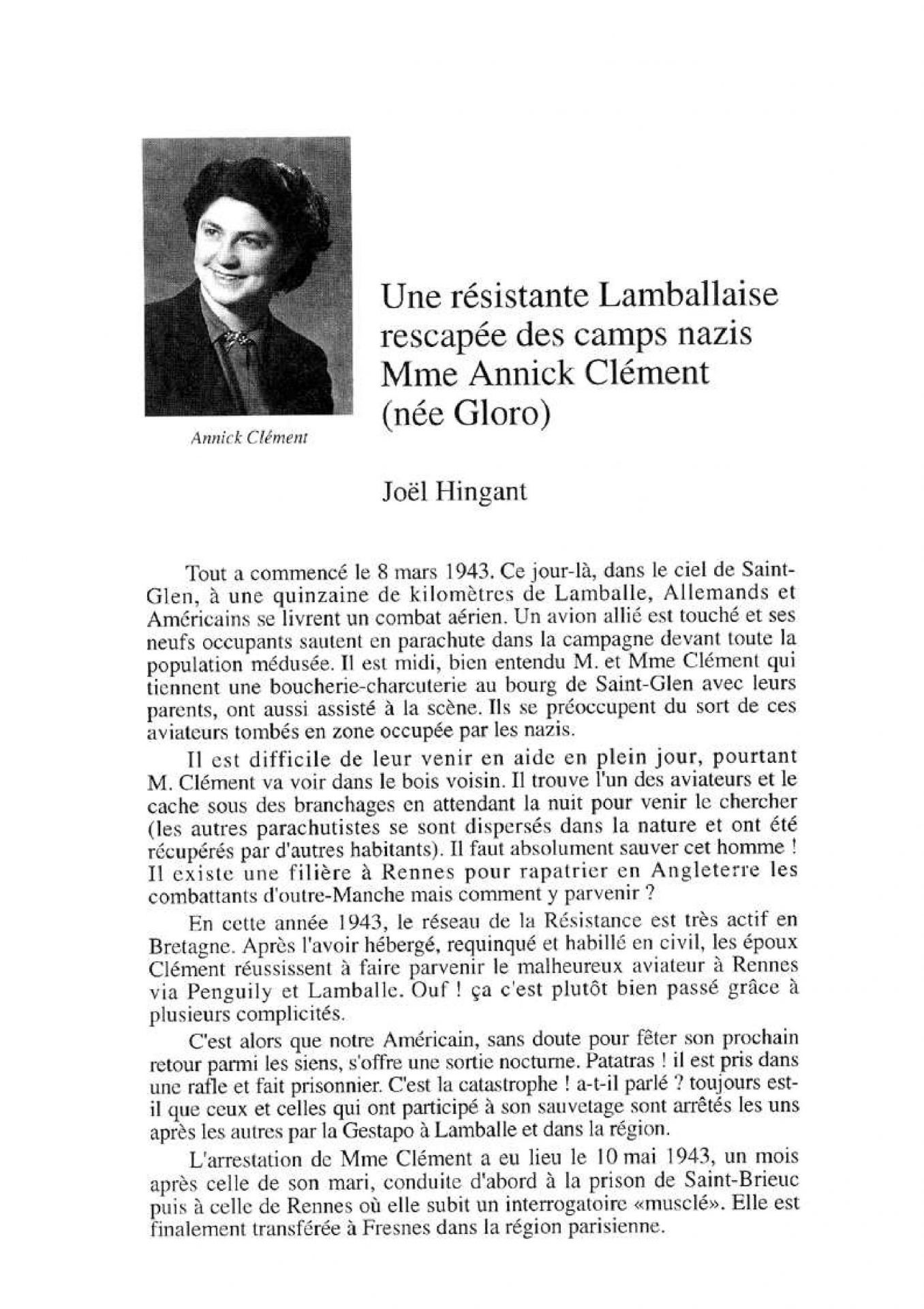

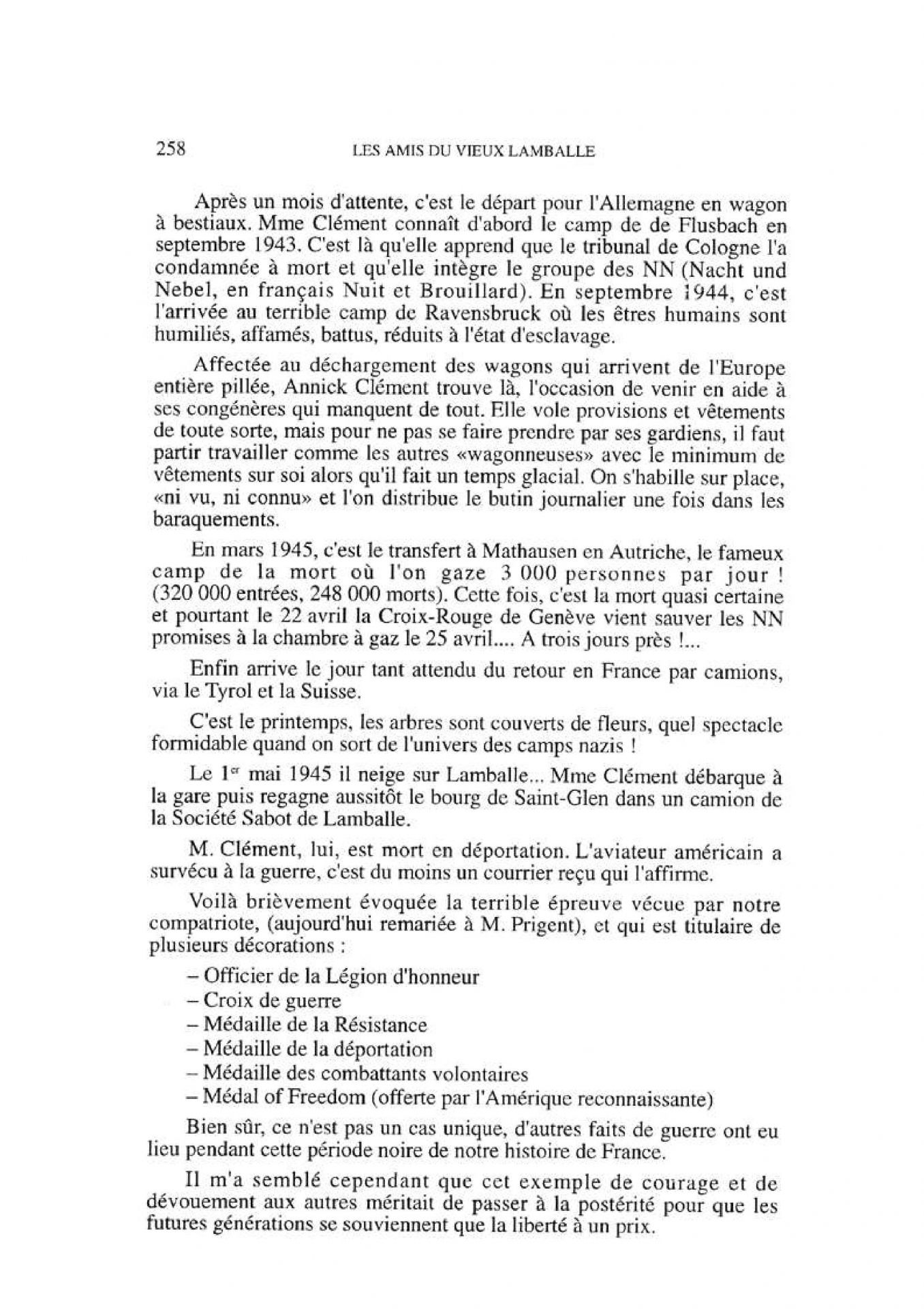

- (Pilot) 1st Lt. Otto A. BUDDENBAUM, service number O-435852, born on 29/08/1918 in Kevil, Ballard County, Kentucky, KIA

buried in Section C, site 658, Golden Gate National Cemetery, 1300 Sneath Lane, SAN BRUNO, CA 94066 (USA)

1st Lt. Buddenbaum in USAAF pilot uniform, with his rank of Lieutenant and pilot's plate on his jacket.

Photo Buddenbaum family

- (Co-Pilot) 1st Lt. Warren Peter EDRIS Jr., service number O-789381, New-York, POW

- (Navigator) 1st Lt. Wilton Douglas BIGGS, service number O-789381, POW

- (Bombardier) 1st Lt. Joseph Cuderly WILKINS, service number O-724179, born on 22/06/1919, Nebraska, POW

- (Eng. / Top turret gunner) T/Sgt. Robert GUTHRIE, service number 15069779, born on 19/10/1917, West Virginia, POW

- (Radio operator) T/Sgt. Sylvester Louis HORSTMANN, service number 37059997, born on 05/04/1918, Missouri, POW

- (Bowl turret gunner) S/Sgt. Robert Stanley LISCAVAGE, service number 13025759, born on 02/071922, Pennsylvania, POW

-(Left waist gunner) Sgt. Ernest Thomas MORIARTY, service number 11030793, born on 21/02/1922, Winchendon, Massachusetts, escaped

- (Right waist gunner) Sgt. Donald Robert HUDDLE, service number 18040529, born on 29/09/1919, POW

- (Tail gunner) S/Sgt. Eulis Eugene SMITH, service number 34189597, born on 06/11/1909, POW

THE STORY

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

Friday 8th March 1943, Plouguenast, 'Côtes Du Nord' (Brittany). Village "Le Cas Rouge", fall of B-17 F, s/n 41-24514, code BO-R, of 306th Bomb Group, 368th Bomb Squadron. 8th Air Force.

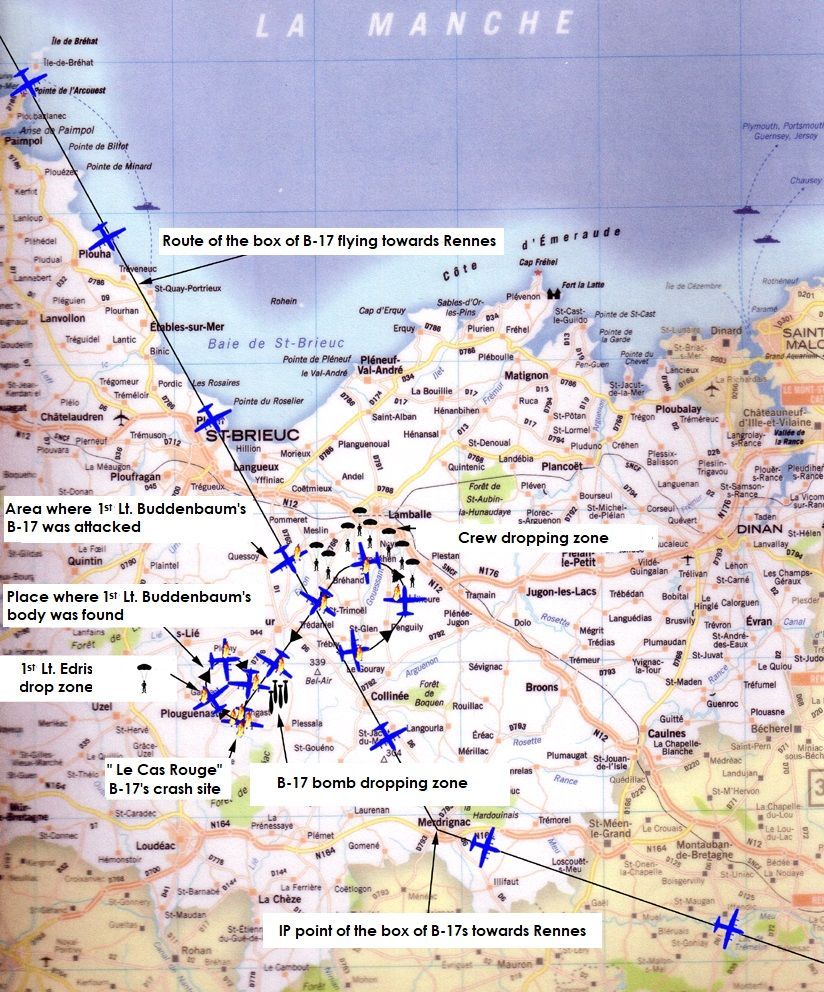

Historical context: the high command of the Anglo-American Allied forces in England, early in March 1943, decided that a bombing mission should take place on the railway marshalling area located east of the Rennes station (Ille and Vilaine, Brittany). For this, good weather conditions were expected, which meant clear skies for a precise approach to this important crossroads on the Paris-Brest line. The Germans have occupied Brittany (which the Americans call Brest Peninsula) since June 1940. For 33 months, they have imposed a strong occupation with consequences on the Breton population, depriving them of FREEDOM and many other things, making life of everybody a hell, without counting the reprisals and the crimes of which they were the authors. Rennes station was a strategic rail axis. It is through this place that all the trains loaded with men, ammunition, fuel, food etc used to transit. In addition, it is also through Rennes that the occupant transported all the materials necessary for the construction of the Atlantic Wall, considering also that the Channel coast was not left out of intense concreting, blockhouses, shelters, firing points, etc ... But also, gigantic bases for their submarines, the U-boots, were built in Brest, Lorient and Saint-Nazaire. The enemy was also strengthening all existing airfields to be able to welcome their powerful air force. It became urgent to hit strongly the supply of the terrible Nazi war machine.

On March 7, the meteorological observers specified a high pressure window over several days. The conditions required for this mission were therefore favorable. The Headquarter gave the order to operate the next day, Tuesday 8 March, knowing also that the information provided by the French resistance at headquarters in London supported this decision. Four Bomb Groups were designated. From 3 am in the morning, a first briefing gathered the pilots in their respective units. As in any mission, exemplary coordination was required. One could not leave anything to chance. The designated heavy Bomb Groups were : the 303rd based at Molesworth Airfield, in Huntingdonshire, with 19 Boeing B-17s, the 305th based at Chelveston Airfield, in Northamptonshire, with 18 Boeing B-17s, the 306th based at Thurleigh, in the Bedfordshire, with 16 Boeing B-17s and finally the 91st based at Bassingbourn, in Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs), with 14 Boeing B-17s, i.e. a total of 67 four-engine aircrafts mobilizing around ten men per B-17, i.e. around 670 men. All this air armada was to be supported by 4 squadrons of Spitfire Mk IV of the Royal Air Force, coming as a protection group against the famous German fighters of the Luftwaffe.

The most important issue for this defence group was gas economy. In fact, we were at the beginning of 1943 and the Spitfire had not yet received the improvement that arrived later. Within this escort, eleven Spitfires flown by pilot officers from Czech groups incorporated into the RAF were expected alongside the bombers, which reassured American airmen. No 313 Squadron took off from Churchstanton in Somerset, No 310 took off from Exeter, and No 312 and 602 took off from RAF Harrowbeer. All of these air bases were located in Devonshire. Their support mission ended shortly before the target, ie Rennes. A new briefing took place at 9:30 am on each base. The crews were formed and received instructions. The pilots also received take-off orders. It was planned at 11:30 am for the 306th BG and 11:46 am for the 91st. For the 305th it was planned at noon and for the last group 12:05. On the Thurleigh RAF base (Devon), the B-17 registered 41-24514, coded BO-R, belonging to the 368th Bomb Squadron was in preparation for this mission towards Rennes. Nearby, on the same base, 15 other four-engine aircrafts were still being prepared for this same mission. The armament technicians were at work : one group was busy loading the bombs and another group was supplying machine-guns with 50-caliber bullets, which meant about 400 kilograms of cartridges for the entire plane. The refueling was operated with great care, due to the dangerous nature of the operations. The mechanics were not left out because this plane had engine problems during the last mission, and all the maintenance had to be reviewed very seriously. A general revision had been carried out. The aircraft was declared good for flight.

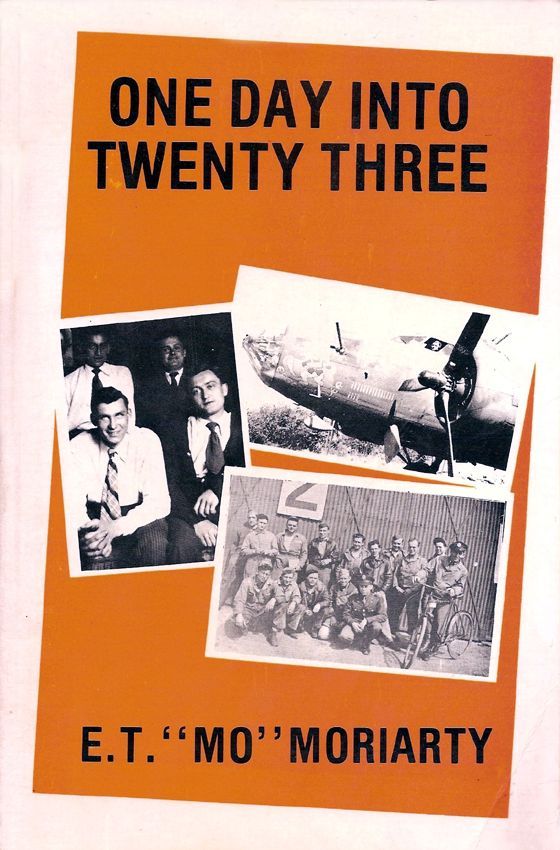

Suddenly the sound of an engine drew attention. A van stopped by the plane. This vehicle carried the full crew, about ten men. In his book "One day into twenty three" written during his retirement, Sergeant Ernest Moriarty paid close attention to his brothers in arms. So young people engaged in such difficult missions, they saw experienced much more than friendship between them, but great brotherhood. He talked about this in a simple but sensitive way.

Otto Buddenbaum - Photo Buddenbaum family

The pilot was 1st Lieutenant Otto Buddenbaum, 26-year-old, nicknamed "Budd" by his comrades. He was coming from Atwater, California. He was an experienced pilot, tall stature, with blond hair, very patient, with the soft voice of the southerners. He presented behind this aspect a firm and resolute character. He was considered one of the best pilots in the group. His crew, or those who have flown with him, trusted him totally and considered him as a highly appreciated chief. The co-pilot for this mission was not the one who was usually in this position, who was ill. At the briefing, the captain asked 1st Lt. Warren Peter Edris (see Mr. Messenger's story below) to come and asked him if he was ok for the mission. He answered positively.He was originally from Manhasset, Long Island, New York State. The navigator was 2nd Lieutenant Robert Biggs, from Wishita, Kansas. He was a tall, thin man with dark hair. A quiet man with a very calm temperament. He was the sole man married in the crew. 2nd Lieutenant Joseph Wilkins was the crew's bomber, from Washington DC ; very dynamic and very friendly, he had the nickname "Little Jo" because of his small size. Sergeant Robert Guthrie was from Padan City, West Virginia ; soft voice and a keen sense of humor. We never knew wether he was joking or wether he was serious, said Sergeant Moriarty. He has been interned at Stalag 17B Braunau Gneikendorf, near Krems, Austria 48-15.

Sergeant Sylvester Horstmann was a personal friend of the pilot, Lt. Buddenbaum ; the two men were very close and were often together in a crew. Their two German-sounding names made them nicknamed by the rest of the group "the German crew." Happy, fun, with red hair, contagious laughter, he was the crew's radio operator. He was originally from Brookport, Illinois. Sergeant Donald Huddle was from Red Cak, Iowa ; thin man, deeply religious, calm, with great inner strength, he was the right side waist gunner. Sergeant Eulis Smith, from the hills of Tennessee, nicknamed "Smitty" by his friends, a tall man, had the particularity of always chewing gum. Blond hair, with a parting in the middle, he was not looking like a machine gunner but yet he occupied the ball turret under the aircraft. Sergeant Robert Liscavage, originally from Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, was the tail gunner. He was tall, thin, with high cheekbones, and black hair. Very serious but full of delicious humor, he was nonetheless very discreet. He always said he was the old man of the crew. Taken prisoner, he was sent at Stalag Luft 3 Sagan-Silesia Bavaria, then at Nuremberg-Langwasser.

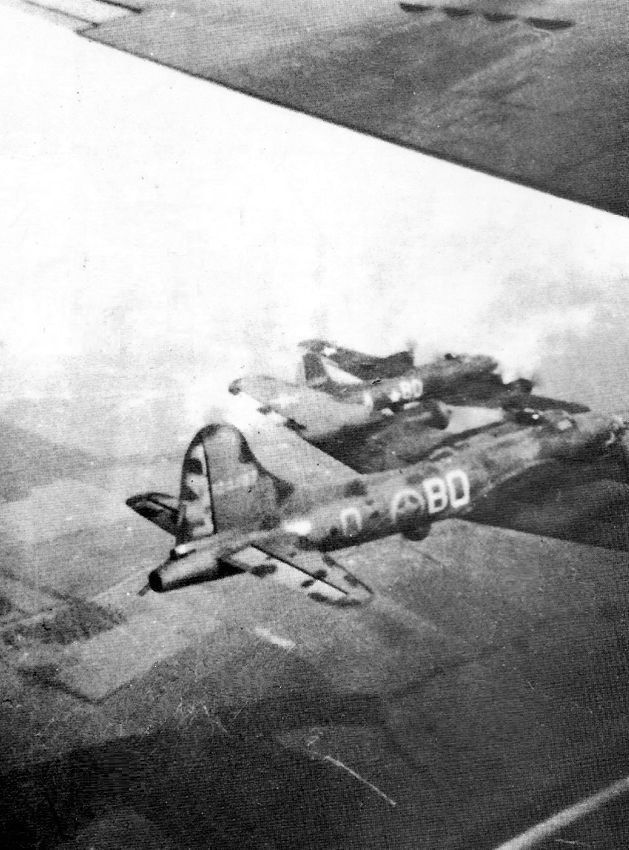

B-17 of 306th BG in flight

Photo unknown source

It was 11:15 am at Thurleigh airfield. The 16 heavy bombers were preparing for takeoff. Lieutenant Buddenbaum's B-17 was finally ready for its mission. All the men were ready on duty. Arrived at the end of the runway, the 41-24514 was positioned. The pilot applied the brakes and applied power, driving the propellers at their maximum. The take-off order was received, the pilot released the brakes pulling the heavy aircraft forward. The speed got faster and faster and then suddenly they took off. Sergeant Moriarty, in his book, explained that it took almost the entire length of the runway to get off the ground. The runway was already far, the pilots were busy checking all the onboard instruments. The aircraft was gaining altitude. A little delay had been taken but it was easy to fly towards the group of other aircrafts in order to reach the assembly point over the English Channel, off Portland. In the radio, some other aircrafts already informed about problems to the base, often mechanical problems. They received an immediate return order. Out of the 67 B-17s that took off that day for the mission, 13 returned because of such problems. Lieutenant Buddenbaum's B-17 was ordered to position itself in the formation known as the combat box, the last aircraft on the far left, in the last group of the formation. This position was not appreciated by airmen. They call it "The Purple Heart", named after the supreme award given to fallen or seriously injured soldiers. In other groups, this position was called "Coffin corner". Sergeant Moriarty wrote that this day, as a left waist gunner, he saw the other aircrafts on his right while, and on the other hand, he saw the blue sky which, for the moment, was not punctuated by enemy aircrafts.

USAAF gunner's wing

Crossing the Channel went quitely. Suddenly appeared through the windows the reassuring presence of the Czech friendly aircrafts, with their 11 Spitfires. Americans were reassured to see them at their side. Through the loudspeaker, the pilot's voice announced the approach to the island of Guernsey, where anti-aircraft battery opened fire. The formation was out of range, because it flew around 20,000 feet (approximately 7,000 meters), then suddenly the loudspeaker sounded again: "the Breton coast is in sight on the horizon but be on your guard, ten enemy hunters are reported ". It was on near of the island of Bréhat that a dogfight began, between the Spitfire of the Czech Flight-Lieutenant Benignus Stefan and the Unteroffizier Heinz Butteweg (Focke-Wulf 190) of the 8./JG 2 (8th Staffel, from Jagdgeschwader 2 "Richthofen", 2nd Fighter Squadron). The fight was terrible. It led to the death of the Czech pilot who crashed on the 'Pointe de Bilfot' in Plouézec, near Paimpol (see biography of Benignus STEFAN).

The Uffz. Heinz Buteweg claimed this Spitfire at 2:12 pm, at 7,500 m ; he apparently attacked the protective Spitfire formation about 500 m above the B-17s. The III./Gruppe of the Jagdgeschwader 2 was commanded by the Gruppenkommandeur, Hauptmann Egon Mayer. The Stab III and the three 7, 8, and 9 Staffeln (squadrons), which made up the III. Gruppe, were based in the Vannes-Meucon airfield since November 22, 1942. Hptm Egon Mayer took command of the group on November 1st. Since this month of November, the Hptm Egon Mayer was the author of a new technique of bomber interception which consisted in arriving slightly above the "box" and in front of it ; the Fw 190 were then diving at the last moment in a full throttle.

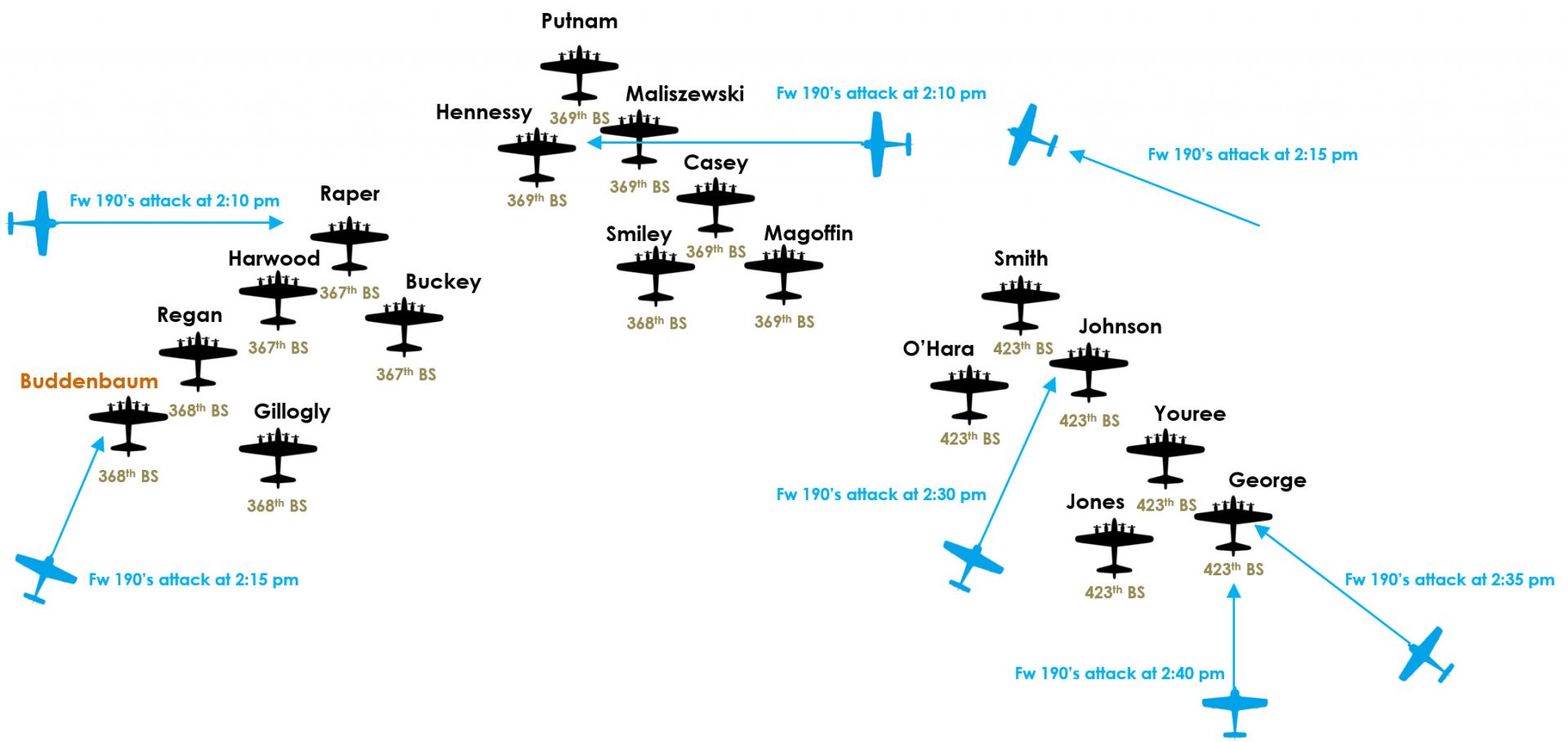

Map of combat of du 306th Bomb Group

It was two o'clock. The mission continued, the 54 B-17s were still in very close formation. Maintaining these flight conditions was tiring for the crews to avoid collisions. The sky was still azure blue, which allowed great visibility. You could see the enemy coming and react immediately if necessary. The B-17 s/n 41-24514 did not have nose art, i.e. a name or design on the nose. This aircraft had been allocated to several crews, unlike others which were personalized because they were still in the same hands. The formation was currently flying over the region of Moncontour. It was a little after 2 pm, when suddenly the two pilots noticed surprisingly that the two internal motors, that is to say the two closest to them, were losing power. Very quickly reduced by half, they could not remain within the formation because of the loss of altitude and speed. The flying fortress very quickly became vulnerable. Lieutenant Buddenbaum immediately informed the crew. The men were all worried. The situation was serious. The aircraft was still losing altitude. Piloting was getting harder and harder. The efforts of the pilots were remarkable. “Budd,” as his friends called him, was had to make a decision quickly. Suddenly, there was an alert ; a Fw 190 came quickly from below and began to fire. The machine gunners opened fire on the enemy, unfortunately without hitting him. He fired three short bursts of 20 mm and one shell went through the right wing, another through the left wing, and then a third hit the right internal engine, igniting it. The upper turret was also seriously hit but without injuring the gunner. The situation was critical. The B-17 seemed to have been jointly claimed (according to the archives of JG 2), at 2:15 p.m. at 7,000 m, square 15 west, by the Uffz. Friedrich May of 8./JG 2, then undoubtedly chased by Fw 190 of Lieutnant Hugo Dahmer, of 7./JG 2 at the same time and at 6,200 m in the same sector.

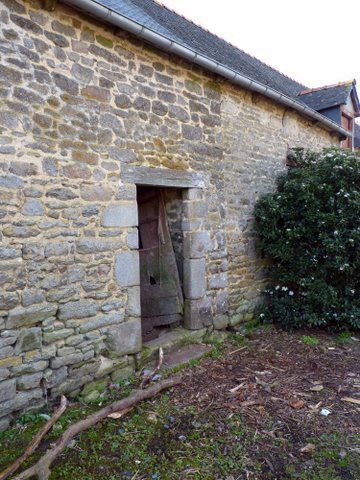

The B-17 was no longer maneuverable. At this moment she described an easterly curve flying over the Collinée region. Then suddenly the pilot's voice sounded: "jump, jump quickly". The crew did not waste time and everyone put on their parachute. Everyone helped each other before the big jump into the void. But the door refused to open. It has been seriously hit by the shells. Lt. Edris reacted quickly to this situation and kicked the door hardly, which finally opened and fell into the void. This door was found in the town of Trébry at a place called "Beauvais", just on the edge of Bréhand by Mr. Defin. During this eventful evacuation, the rear gunner, Sergeant Liscavage, became unwell and lost consciousness. Very quickly brought by his comrades to the opening, and in contact with the fresh air, he recovered his senses but had to be helped to jump from the aircraft. He was injured on landing. Quickly arrested by the Germans, he was taken to Saint Brieuc hospital. The other airmen touched down on Breton soil in a geographical area going from Bréhant to Trébry and Saint Glen. Sergeant Ernest Moriarty landed in a field near "La Ville es Renault" in Trébry. At that moment, a local resident was busy with his beehives, when he saw this parachutist falling not very far from him. He immediately decided to help him. "Mo," as all his friends called him, said that when his parachute opened, the shock was particularly severe. Quickly he lost his lined boots and therefore arrived in the plow in socks. The parachute had remained hanging on a tree. In the company of Mr. Deschamps, he made sure to recover it and hide it in a safe place. Always helped by his savior, he was hidden for the end of the afternoon. Then in the evening, he was directed to the farm of Monsieur and Madame Fraboulet, in the village of "La Touche" in Trébry where this courageous couple put him out of danger, in a barn. He was comforted and dressed in civilian clothes. He stayed there for 5 days, hidden in the barn at night and then, during the day, behind the farm near a centuries-old chestnut tree.

"La touche" en Trébry, chestnut where Sergeant Moriarty was hiding during the day

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

Entrance of the barn where Sergeant Moriarty wasspending the nights.

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

Inside of the barn.

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

Mme Loncle, née Fraboulet, was 14 years old when Sergeant Moriarty was hidden in this barn in her parents' farm in Trébry.

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

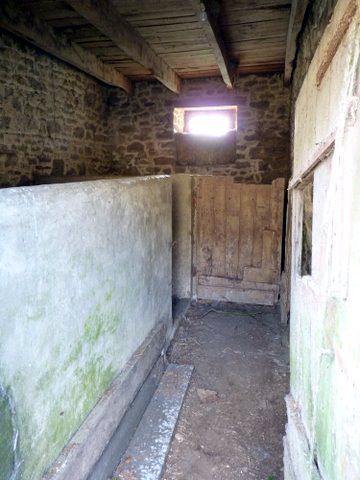

From this cache, he saw the Germans passing on the nearby road. Then he was directed to Collinée, where he received help from resistance fighters. His journey took him through Brittany, then to Carantec, Finistère, where he received assistance in the Sibiril escape network. In the evening of March 30, he embarked on board the fishing boat "Jean", along with 18 other people. The "Jean" was steered by Mr. Jean (François) Gestalin, aged 21. Born June 18, 1921 in Riec-sur-Bélon (29), he joined the Free French Naval Forces on April 19, 1943.

The passengers of the boat "Le Jean" - © Photo with courtesy of Laurent Laloup - Source : www.francaislibres.net

The crossing was very eventful, the engine quickly broke down. The sail had to be hoisted, and the boat crossed the Channel in very rough seas, with the risk of being caught by the German navy. The next morning, the English coast appeared. It was not without difficulty that the escapees were recognized by the British Coast Guard. It took 21 days for Sergeant Moriarty to reach the English soil. He was the only one to have succeeded in this comeback. After the war, he enjoyed coming and meeting the people who had helped him by making several trips to Brittany. He died in February 2000.

Model kit Le "Jean". Thanks to maritime museum of Carantec.

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

Lieutenant Edris escaped via Languédias and Dinan, but was captured in Paris with all the family who hosted him. He was transferred to Stalag Luft 3 Sagan-Silesia Bavaria, then to Nuremberg-Langwasser..

Photo source unknown

The Sergeant Guthrie injured one eye as he entered a thicket. Followed by an enemy patrol, he was captured quickly. The Lieutenant Biggs was unlucky ; he fell heavily on the ground, in a broom moorland at a place called "Vaudehay", near the village of "Corbière" in Trébry, and broke one of his legs. He was hidden by a lady but was suffering and had to resolve to surrender. Arrested, he was taken with his comrade Guthrie to Saint Brieuc Hospital, where they found Sergeant Liscavage, already hospitalized. The Germans announced to Liscavage the death of his pilot in the following days. They told him he had received military honors. Lt Biggs was interned at Stalag Luft 3 Sagan-Silesia Bavaria, then at Nuremberg-Langwasser.

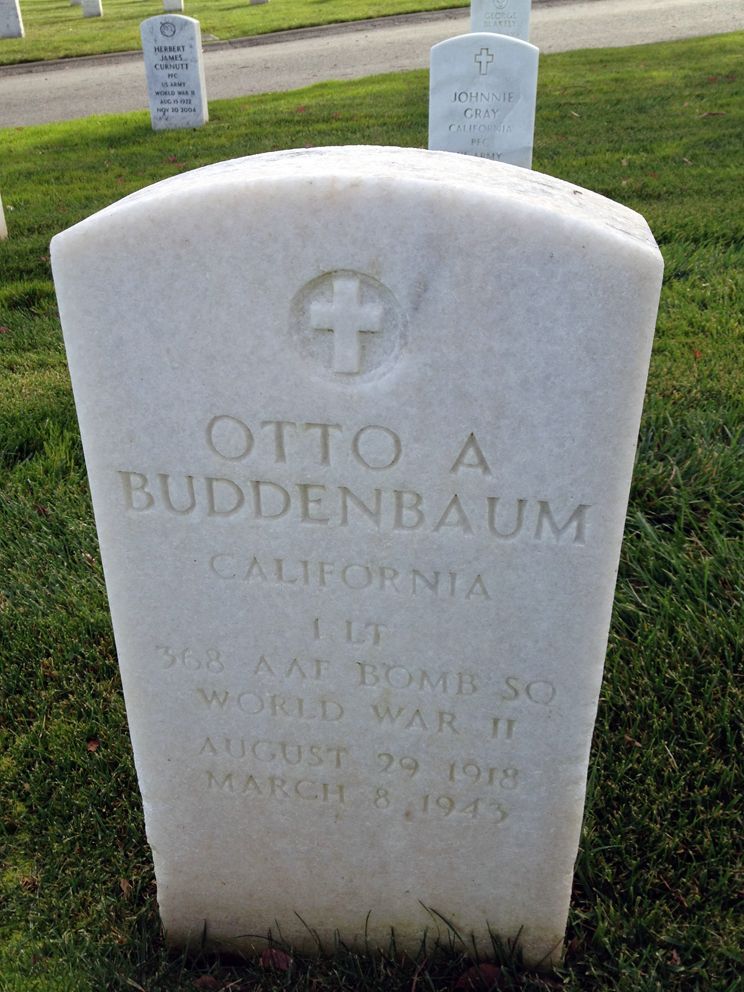

Mister Clement, a merchant in Saint-Glen, saw the aircraft in distress from which the American airmen were bailing out one after the other. One of them was blown by the wind towards the village. Mister Clement quickly took his bike and walked over to help him. This airman was Sergeant Sylvester Horstmann. The latter, touching the ground, hurt his shoulder badly. Mister Clement discovered him in a small grove. Mrs and Mister Clement hid the sergeant in Saint-Glen, but rapidly a serious escape route had to be found. They found it two days later and they took him in Rennes, from where he had to leave for Spain via Paris. After a few days spent there, Sergeant Horstmann allowed himself an evening outing in the city despite the risks. He was stopped by a German patrol not far from where he was hiding. Immediately imprisoned, he left the following days for a Stalag Luft in Germany, Stalag 17B Braunau Gneikendorf, near Krems in Austria, to join many other Allied airmen deported. As a result, 10 people from Saint-Glen were arrested by the Germans and sent to a concentration camp in Germany. Mister Clement did not come back, like two other people who died in these bloody places. Mrs Clement lived for two years in the hell of the death camps (see her testimony below from the "Friends of Old Lamballe notebooks", which we publish with her kind permission).

The Lieutenant Wilkins, the bomber in charge of the drop, landed in a large wood between Trébry and Bréhand. He managed to hide but was arrested the next afternoon when a patrol saw him crossing a field. He was transferred to Stalag Luft 3 in Sagan-Silesia Bavaria, then to Nuremberg-Langwasser. Sergeant Huddle touched the ground near a farm, in the village at a place called "La Cabane" in Trébry. During his descent, he was hit by a projectile fired from the ground. He was temporarily placed with a local resident, with a hemorrhage, but was quickly directed by the occupant to Saint Brieuc hospital. Sergeant Smith, who was the bowl turret gunner, was hidden by people from Trébry. Everything went well. However, the Felgendarmerie found him with precision a few days later in his hiding place. Germans had obviously been informed. Sergeant Smith was arrested and like the others was sent to Germany, and was liberated only at the end of the war. He was sent at Stalag 17B Braunau Gneikendorf near Krems.

Lieutenant Hugo Dahmer

Photo © with courtesy of www.jagdgeschwader5und7.de

In the aircraft in distress, only the pilots feared the tragedy. It was around 2:15 pm The sky was still azure blue. The Fw 190 was still attacking its prey. The pilot, Lieutenant Hugo Dahmer, of 7./JG 2, approached and flew along the B-17 for a while. The courageous Lieutenant Buddenbaum said briefly to Lieutenant Edris, "We must not have our plane crash on a village". The worry of the end did not alter the sense of responsibility of these young men. The shipment of bombs was still on board. They had to drop it. Everything happened quickly. The chief pilot ordered his co-pilot to drop the bombs. Lieutenant Buddenbaum spotted a steeply sloping bocage ground and chose to drop there. Two bombs exploded, the other eight fell into the ploughs without exploding. The bomber continued on its last flight and followed a curve on its way back to the west. The altitude got lower and lower and the fire spread to the rear. On the outskirts of Plouguenast, Lieutenant Edris jumped. He landed in the farm "La Bruyére", located north of the town. The farmer witnessed this tragic scene and hastened to help the American. The parachute was quickly hidden behind buildings. Everything was going very fast. They had to hide the co-pilot. In the farm this was not a good solution because the enemy was about to come. A sunken path far from the farm was quickly found. The Germans got excited and increased their patrols. An hour later, they invested the farm. They did not find anything and left two hours later. The B-17 now only had the brave pilot on board, the aircraft was still following a big curve. Noises were heard coming from the burning aircraft. “Budd”, as his friends called him, jumped. But he was much too low. His body was found by the roadside, in a place planted with pines in the village of "Avaleuc" in Plémy (see testimony of Mr. Ferdinand Cadoux below). His parachute hadn't had time to open. He was buried in the cemetery of the West, in Saint Brieuc, and then, after the war, was repatriated to California near his family.

M. Cadoux, show the place where the body of Lieutenant Otto Buddenbaum was found..

Photos Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

It is expected that the pilot put the autopilot on to make the aircraft crash where the bombs had fallen. In its last moments, the bomber flew over "Le Saut Thébaut" in Langast, then over a large valley, to crash with an enormous noise on a sloping meadow a dozen meters from the farm of the "Cas Rouge" and from the first houses of "La ville Hellio". The aircraft fire raged, releasing tall flames and intense black smoke that rose high into the sky and was visible from far. The bullets left on board crackled for half an hour. The aircraft slowly consumed itself. Three burning engines, in this furnace, fell off and rolled down the slope, and stopped only when blocked by an embankment. The B-17 fell a little short of where the pilot wanted it to be. A tragedy was just avoided because the houses were very close, leaving the inhabitants in a great fear. A lady, who has since died, lived a little further away and was at her window at that time. Not fearing anything due to the distance that separated her from the aircraft, she witnessed this tragedy. It was 2.15 pm. The 53 other bombers accomplished their mission and the Rennes marshalling yard was destroyed. But unfortunately, several bombs also fell on the neighborhoods near this station. The store "L’Économique" was particularly affected with around fifty women workers killed, as well as the "Champ de Mars" where the funfair was in full swing during these 'Mardi gras' Holidays. There were 300 civilian casualties. On the way back, another B-17, # 41-24588, was attacked and shot down by German fighters over the English Channel, off the Normandy coast. He sank without a trace.

Jean Michel Martin - ABSA 39-45, le 21 avril 2011.

TESTIMONIES

Mister André Defin, living in the village of "Beauvais" en Bréhand.

I remember very well that day. It was a beautiful day, the sky was very clear, azure blue. It was the beginning of the afternoon. My brother Louis had started to cut my hair. I was sitting in a chair in the middle of the yard, my arms resting on the back of the chair. Suddenly we heard a low purr high in the sky. The air seemed to vibrate. It emitted a deafening noise. We knew they were aircrafts because at that time it was very common. We couldn't see them because they were at a high altitude. After the war, one of the airmen came to visit us and he told us that the aircrafts were flying that day at 7 000 meters (Sergeant Ernest Moriarty).

We insisted and were able to see several dozen bombers flying in close formation. Suddenly we heard the sound of enemy aircraft firing. The fighters, at that time, flew at high speed even when flying low. The attacks followed one after another, when suddenly we saw one breaking away from the group. He was declining in altitude and was staying behind. He was certainly hit because a plume of black smoke came from an engine. We were following the development of this tragic situation when suddenly something was seen falling in a spiral, alternately shining in the sun, like a mirror, and clearly coming from this distressed bomber. We thought of a bomb, but when it reached the ground, no explosion was heard. Immediately, from our orchard behind the house, we heard a noise, like a snap. We were scared, but nothing happened. Our gaze was always on the aircraft from which we could see the white corollas of the parachutes escaping. There were several who swayed quietly down. The aircraft disappeared from our sight. The Germans had gone mad. They were running everywhere. From our village, we wanted to know what had fallen a little further, in the village of "Beauvais" in Trébry. We were not alone in witnessing this tragedy; about ten people went to the scene. There, in the middle of the meadow, lay a large rectangle of khaki color with a window and a handle. Cautiously, with a pole, we hit what turned out to be the aircraft's door ; fearing the Germans, no one wanted to get it back. My brother decided to take him discreetly at home. What he did. Inside, the aluminum was very shiny. The glass was plexiglass. Children broke this window while playing with the door.

The door was found in the middle of this field in Beauvais en Trébry.

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

The family Defin shows the door of the B-17 recovered on March 8, 1943

Photo family Defin

In the evening, my brother and I wanted to see what had fallen in the orchard. We looked around for a while, then a khaki green helmet with two earphones was discovered under an apple tree. He bore traces of blood. The gendarmes recovered him the following days. An aviator landed not far from where we live, at a place called "La cabane". He was injured and bleeding. It appeared he had been hit by a projectile from the ground. He was laid in a bed in a local resident's house and, given his condition, the Germans took him to the hospital. Another aviator fell into a broom moor at a place called "Le Vaudehay" near "Corbière". He was very tall and I think he had a rank. He had a leg pain ; a lady offered to host him at home, but it was only for a short time because his injury forced him to surrender to the Germans. At the hospital, he was told it was a fracture. His parachute had been taken by two young people who wanted to have shirts made for them in the canvas. At that time, we lacked everything. Very quickly, the gendarmerie, well informed, came to retrieve this parachute. This is what I remember about it.

Louis DEFIN - Photo © Françoise GICQUEL

Louis Marie Constant DEFIN was born on December 23, 1921 in Bréhand (22). He was the son of Louis DEFIN and Marie-Joseph GLATRE. His mother lost 2 brothers in WWI : François and Mathurin GLATRE. The family lived in Beauvais in Bréhand. Louis had an older sister, born the same year as him, and two brothers named Pierre and André (our witness). He was a farmer. During the war, he was resistant to the 'Service du Travail Obligatoire' (S.T.O. - Mandatory work service). He joined the Resistance at the end of July / beginning of August 1944 (at the time of the Liberation) within the F.T.P.F. of the Valmy Battalion. On August 17, he voluntarily enlisted to continue the fight. It was integrated into the 3rd Company. The Valmy Battalion took up position on September 7, 1944 at Sainte-Hélène (56), on the Lorient front (56). Louis DEFIN was seriously injured in the intestines by shrapnel on September 8 in Nostang (56). He was transported to Auray hospital (56) where he died after suffering on September 16, 1944 at 7:30 p.m. He was posthumously approved for the rank of soldier 2nd class. His mother went to look for the body with a cart in Auray. He was then solemnly buried in the Bréhand communal cemetery where he still rests. A commemorative painting made in his honor is kept by his nephew, Denis DEFIN, as well as a commemorative frame by his niece, Françoise GIQUEL. His name is inscribed on the commemorative monument of La Vallée, in Trédaniel (22) (name DEFFIN) and on the War memorial in Bréhand.

Memorial tablet Louis DEFIN - Photo © Françoise GICQUEL

Memorial tablet Louis DEFIN - Photo © Françoise GICQUEL

Sources :

- ADCA 2W236 Survey town hall Bréhand, File Vincennes, File DAVCC, "Ami entends-tu n°125"

- Family documents and information provided by his niece Françoise GIQUEL (email exchanges on November 12 and 13, 2016)

- Interview with his nephew Denis DEFIN (interview of November 12, 2016)

Jimmy TUAL, member of the Friends of the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation of Côtes D'Armor and of the ABSA 39-45 - November 2016

Mister Albert Morin, Plouguenast, Village of "Le Cas Rouge".

I remember that terrible day very well. It had started well. The weather was wonderful. Spring was beginning to appear all over the countryside and in the gardens. It was 'Mardi gras' holidays. Part of the morning, with our friends, we had played the horse game. This game consisted of passing a long string under one arm, then behind the neck and back down under the other arm. The comrade behind held the guides and so we ran, racing with others. At that time, no games or toys like today. Let’s not forget it was war. Regularly, we witnessed the passage of the Allied bombers, in large numbers, which flew to Saint Nazaire or Lorient. Often a noise in the sky caught our eyes. Air combats were frequent. It was terrible and scary. We were afraid.

Around half past noon that day, we returned home for the lunch. Noon for us was sunny time. The occupier was two hours older than us. Our mother made pancakes. I remember it very well. At our table, near my grandfather, sat the postman and a few neighbors who had been asked for a drink. Our parents ran a farm in the village of "Ville Hellio" about 30 meters from "Le Cas Rouge". One of my memories was also this machine called the "Loco", a steam locomotive that awaited the threshing of the following summer, parked in our yard. We then ate and the meal lasted a little longer than usual. Suddenly we heard the hum of aircraft engines passing through the sky at high altitude. They were heading south. Then a terrible noise was heard. We went out with our parents to see what was going on. In the distance we saw a bomber blazing flames behind an engine. It was alone, detached from his formation, and losing altitude. Then multiple bright white dots appeared in the sky. They looked like stars. The sun made the canvas of the parachutes shine. We saw the airmen leave their planes one after the other. There was panic among us because the danger was growing, the bomber came in our direction with a terrible noise. So what happened next ? It seemed to have made a passage to drop his bombs in the large field in front, across the road. This large field was steeply sloping. Very steep, it reached an altitude of 195 meters in its upper part. At that time, it was divided into small plots bordered by wooded slopes. Two bombs exploded, leaving craters about ten meters in diameter, the others did not explode. We saw this only the next few days, without getting too close as German sentries roamed the area. The aircraft seemed to have flown west and then it came back towards us in a steep curve. It crashed fifty yards from our house with a terrible noise. A neighbor, who had fought in WWI, seeing the danger coming, ordered us to lie down on the floor of our house. We waited like this for a quarter of an hour before going out. We walked over the cartridges that had fallen in the courtyard. There were thousands of them, whole wheelbarrows. The aircraft's carcass was on fire. The tall flames released intense black smoke. Suddenly, we were very scared because a German fighter flew very low above us and we did not see it arriving. It came to realize what it had done. That afternoon, we only saw one enemy aircraft. The surprise was total when we noticed that the tail of the bomber had fallen, resting on the ground of our orchard, very close to our house about fifteen meters. The tail wheel had hung on the trunk of an apple tree. After the war, we called it the American apple tree. You have to imagine this rear part of the bomber which had detached itself coming to rest in this small orchard, distant from the carcass of about eighty meters, without touching the oaks which surrounded this plot.

Garden where the tail of the B-17 fell ; in the distance the field of the bombs.

Photo Jean-Michel Martin (ABSA 39-45)

There was no damage in this place, nor in our homes. We risked that day to disappear in this tragedy. All around our home, the ground was strewn with pieces of metal sheets thrown out during the collision with the earth. A radio from that aircraft had been thrown and passed through the roof of a chicken coop. Three of the engines had detached from the wings and rolled across the bottom of the sloping field, stopped by an embankment. They were on fire and the blaze lasted a few hours. The huge wreckage of that plane had been on fire all afternoon. In the field where the bombs had fallen, one of our neighbors, Mr. Hervé, had worked all morning making bundles. By noon, he had left everything including his tools. He had planned to come back after eating. He found nothing. It is a miracle that he was able to escape an inevitable death. At the end of the afternoon, we saw a German column of about 20 men arriving. This did not reassure us. They requisitioned the farm next door, leaving little space for the farmer and his family. They were coming to guard the remains of the aircraft. They stayed more than a month at the "Cas Rouge", relieved every weekend. They came from the camp "La Secouette" in La Motte. We don't have good memories of those Germans. Some thought they could do anything. We had to hide our bread. They took eggs, vegetables… They really didn't mind. Others got mean after drinking. We were hardly reassured. They really liked "La goutte", our cider brandy. Cider, they knew how to find the barrels. A neighbor remebers : the Germans had requisitioned our farm for the most part. One evening, soldiers who had been drinking heavily and who were lying in our hangar started firing their rifles through the metal sheets. Sixty-eight years later, the bullet holes are still visible. At the beginning of April 1943, a whole armada of trucks arrived in the village. Many soldiers helped to pick up the wreckage of the bomber. A crane truck placed all these metal parts on the platforms of the trucks. They left nothing. A team of German deminers had come in the days following the fall to defuse the unexploded bombs. They passed through the village around eleven in the morning, begging us to open our windows and ordered us to hide inside our homes. It lasted one hour. They stayed for about three days. Everything went without incident.

I realize today that this dramatic event could have been even more so if unfortunately our village had been affected. It came close to it. We were really very lucky

Mister Ferdinand Cadoux (retired farmer) : discovery of the body of 1st Lieutenant Otto Buddenbaum on March 8, 1943 at the Village of 'Avaleuc en Plémy' (22).

I remember this sad event that occurred in my childhood. It comes back to me from time to time in my thoughts. My parents ran a farm in 'Avaleuc en Plémy', which I later took over and which today belongs to my son. It was an afternoon. I was with my father and we had just arrived in the upper fields. A sunken path lined with pines led us there. All around it was also the moor at that time. Today they are fields where corn and wheat grow. Suddenly we heard a noise in the sky. The weather was clear. An aerial combat was taking place in the distance, high in the sky. The aircrafts were continuously machine gunning. It was scary. Suddenly we saw a huge aircraft that was on fire and then several white spots escaping from the aircraft. And we no longer saw it. A few minutes later, it appeared to us again, coming from the direction of the village of Plouguenast, with a fire which had grown in importance. He followed a large curve. He passed not very far from us, very low and then we saw something falling from that aircraft. We waited before heading to this point to see what had fallen. Fortunately, because very quickly several German soldiers arrived on the scene. They knew these lands well, because they often maneuvered there, forbidding my father to come and work there. Sometimes people all around were warned because they were shooting live ammunition at a mound. Then we went back home and in the evening, my father wanted to know what was going on. He decided to reach the place by the small sunken path bordered by pine trees. I was allowed to accompany him. When we got close to the spot, we discovered that a sentry was pacing along the field. The soldier was alone. We waited a while, hidden by the undergrowth, then the German, seeing nothing abnormal, decided to stay at the edge of the national road which goes from Moncontour to Plouguenast. He was about 150 yards from us when we decided to search in this little path. It was there that we saw the body of this hapless airman lying under the trees. A few branches were on him. I think he hit them in his fatal fall. This shocked us. He was killed just after exiting his aircraft, his parachute did not open. After a few moments spent near him, we returned still cautiously to avoid being spotted by the German. Neighbors said that the Germans took the body away the next morning. It was very sad for this young man and his family. My father talked about it throughout his life. This dramatic event had moved him.

Jean Michel Martin, June 20, juin 2011.

Mister Messager's story : the escape and the capture of Lieutenant Pete Edris

Lt. Pete Edris bailed out from the front door of the aircraft, immediately after the bomber and the navigator. Only the pilot remained in the aircraft. Pete Edris landed in a farmyard. His parachute hung on a tree. The farmers came to help him. However, the Germans arrived. Pete Edris was immediately hidden in a pigsty. When the Germans had finished searching the farm, he was hidden in an abandoned henhouse. He stayed there until dusk. He was then taken to a farm and changed his clothes. There, he was introduced to a man with whom he walked to Saint-Brieuc, about 50 kilometers of walking. Arrived in this city, just after dawn on March 9, he slept there all day in an apartment. The same evening, he was taken through Saint-Brieuc to another family who hid him for 3 days in an attic. After these 3 days, another man came to get him. They reached Languédias by bike. He stayed there for two weeks, hidden with a priest. After these two weeks in Languédias, another priest arrived. They both traveled by bicycle on March 27 to Dinan, where Pete Edris spent a night with a family. There, he met a doctor of Haitian origin who lived in Paris. The next day, Pete Edris and the doctor reached Paris by train. The doctor passed him off as a deaf mute. Pete Edris remained hidden for about six weeks in the apartment of the doctor and his wife. However, the Gestapo came to arrest him on May 15, 1943 at the apartment. The doctor, his wife and the maid were also arrested. The four of them were taken to Fresnes prison.

Pete Edris was imprisoned for 77 days in Fresnes, and then was transferred on July 29 to the Luftwaffe. Sent in a transit camp, he stayed there for 5 days before being transferred to Stalag Luft III where he arrived around August 5, 1943. He remained at Stalag Luft III until January 27, 1945, when the 10,000 American and British airmen officers who were locked up there were forced to march west, due to the arrival of the Russians. They walked about 80 kilometers in 3 days and 3 nights in freezing temperatures. They were then loaded onto freight trains and driven to southern Germany. The journey was terrible. They completed it at Moosburg, where they were liberated on April 29, 1945, by soldiers of General Patton's 3rd Army.

Purple Heart

Photo : Air Force Personnel Center - VIRIN: 161215-F-YG475-510

US Federal Government - Public domain

Pete Edris was one of the few soldiers of the Second World War declared dead in action when they had survived. The "Purple Heart" was thus attributed to him posthumously and was given to his mother, before being withdrawn when it was known that he was alive.

APPENDICES

The mission reports of the four Bomb Groups dispatched to Rennes are almost all identical : tonnage of bombs used, enemy air defense, etc... Except as it is often the case for exaggerated enemy claims.

Example of a mission report for the 303rd BG.

Target: the railway marshalling yard, Rennes, France.

19 B-17s dispatched to the target.

Duration of the mission: 4 hours and 12 minutes.

Tonnage in bombs : 10 of 500 pounds. M43 bombs.

Bombing altitude : 20,800 ft (6,340 m).

Enemy aircrafts claims: 4 destroyed, 3 probable, 1 damaged.

The twelve aircrafts headed for Rennes and bombarded the primary target with their 500 lb bombs. H.E. Bombs M43, in good conditions with no cloud cover, no haze and ten miles visibility. Photographs taken by the Group at an altitude of 20,800 feet showed good results, with good concentration near the target area and 10 to 12 hits in the yard area. The Flak over Rennes was light and inefficient, being generally reported to be weak. All bursts were black, but only one crew reported three strong gray bursts. The Flak was light and inefficient near Grandcamp, Saint-Brieuc, and Avranches. A crew reported a very light white burst at Saint-Marcouf, another reported it moderate and white and absent in Guernsey. The Spitfires of 4th Fighter Group, and the RAF Squadrons, were an excellent escort from Guernsey to the French coast and again from Saint-Lô to the English coast. Enemy air opposition was moderate to intense, with around 35 fighters reported. Fw 190s and Me 109s were seen from the French coast to the target and astern about ten miles offshore. During this time, there were attacks with enemy aircrafts in all directions, but mostly coming from 11 a.m. to 1 a.m., from above or slightly below. The colors of the attacking Fw 190s varied, but there were mostly yellow noses with silver-gray belly that predominated.

The plausible claims of the B-17 crews

306th BG - 309th BS.

Around 2:20 p.m., near Saint Brieuc, a Fw 190 attacked at 6,000 m at 3 h from below. Sgt Adams Robert, right waist gunner, fired 3 rounds: " the engine, and tail were hit, the cockpit exploded under my bullets, the engine caught fire with intense flames. This claim is quite legitimate, I am sure I destroyed it ".

306th BG - 423th BS.

Around 2:30 p.m., north-east of Rennes, 6,000 m, just after dropping bombs on the target and turning to take the way back, " we were attacked from behind by a Fw 190 ; the squadron opened fire (from 2 B-17s), numerous impacts hit the aircraft, we saw it disintegrate in flight at a distance of 400 yards (365 m) ". Claimed by Sgt Gibson as tail gunner and Sgt Rogers, bowl turret gunner.

306th BG - 423th BS.

Around 2:35 p.m., near Rennes, around 7,000 m. Attack by a Fw 190 coming from the 4 hours from above, I fired a salvo from about 600 yards (550 m) away. At about 400 yards (365 m), the Fw 190 enveloped itself in intense flames, rolled over and crashed to the ground. T/Sgt W.A. McGregor. Top turret gunner.

306th BG - 423th BS.

At around 2:40 p.m., near Antrain, at an altitude of 23,000 ft (7,000 m), a Fw 190 coming from 6 hours from below, the tail gunner fired, impacts were seen, the aircraft made a complete turnaround, left wing on fire. Report from S / Sgt B.H. Lamb, tail gunner.

306th BG - 307th BS.

Around 2:40 p.m., shortly after the target, a Fw 190 attack at 6,000 m, attacked the formation frontally from the right, then from the left and from below. Bombardier S/Sgt Zabawa fired with the nose gun, after about 40 shots, the pilot Harwood saw the shots hit the enemy aircraft. Pilot possibly dead, no smoke seen.

Bilan des pertes du coté allemand.

The known losses for the Jagdgeschwader 2 are two Bf 109 G-4 : one which crashed in Bosville and the second on take-off on alert, engine on fire, west of Dieppe. This does not correspond to the demands of the crews for the Rennes mission, but for the other Bomb Groups dispatched to Sotteville-lès-Rouen.

It is quite possible to have a legitimate loss with the claim of the Fw 190 by Sgt Adams Robert, for the area of St Brieuc. All the losses of JG 2 are not necessarily counted, in particular the material losses, as far as the pilot is not wounded or killed in combat.

One of the two claims of the 306th BG - 423th BS (between 2:30 p.m. and 2:35 p.m.) corresponds to the loss of the Fw-190 A-4 (WNr. 57184) "H white" of the 4./SKG 10. The Fw. Hinz Hans was reported missing in the vicinity of Rennes during an attack on B-17s on March 8, 1943.

In 2005, during the exhibition at 'Le Rheu' for Harti Schmiedel, we gathered a testimony.

A gentleman, a witness at that time, related: " on March 8, 1943, the day of the terrible bombing of " L'Économique ", I was outside (Le Rheu / Chavagne?) when I saw a German aircraft, which had just taken off from the Rennes-St Jacques airfield, attacking bombers. Almost immediately I saw the aircraft explode in flight and fall. " No details on the point of fall, place of the crash still unknown until now.

Dahiot Daniel (ABSA 39-45)

Report from Mrs Clément, deported for 2 years in the death camps, published in Les Cahiers des Amis du Vieux Lamballe :

We would like to thank the Maritime Museum of Carantec as well as "Les Amis du Vieux Lamballe".

A big thank also to Mrs Clément for the story of her deportation, to Mister Cadoux for his testimony on the discovery of Buddenbaum's body, to Mister Defin and Mister Morin Albert for their testimonies and to Mister Messager for his story, to Mister and Mrs Pierre Morin, Mister and Mrs Loncle, Mrs Loncle (mother), Mrs Prigent and Mrs Le Guevel, Mister Robert and Mister Pierre Mahé.

Grave of 1st Lt. Otto A. Buddenbaum. SECTION C SITE 658 GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL CEMETERY, 1300 SNEATH LANE SAN BRUNO, CA 94066, USA

Photo source unknown

Two commemorative plaques in tribute to Otto Buddenbaum were placed on the war memorials of the municipalities of Plemy and Plouguenast.

Plaque at Plemy (22) Photo © Régis Biaux (Aerosteles.net)

Plaque at Plouguenast (22) Photo © Régis Biaux (Aerosteles.net)

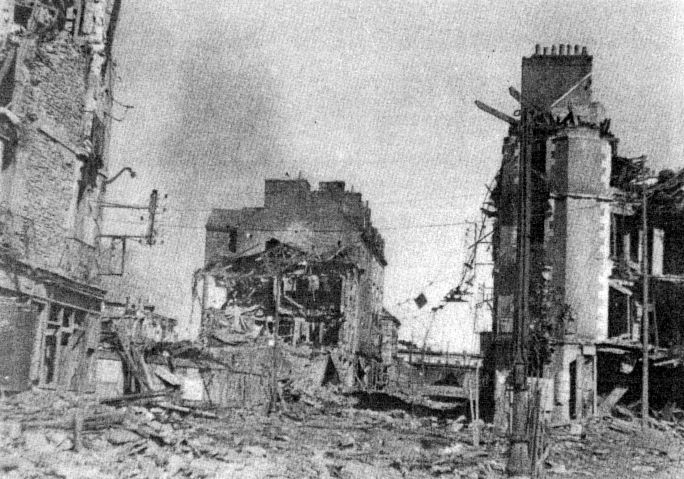

MONDAY MARCH 8, 1943, BOMBING OF RENNES (35)

Below, Rennes after the bombing, newsreels broadcast on March 19, 1943.

A visit to contemporary regional history, through the images at that time broadcast by the Vichy regime, proposed by the INA (Franch National Audiovisual Institute).

Photograph taken from one of the US Bomber Command bombers when the first bombs hit the city.

The weather is beautiful in the spring, and the streets of the city present a cheerful and unusual aspect. It's 'Lundi gras' (pancake day), a lot of stores have lowered their iron shutters, and everyone finds themselves on the Champ-de-Mars where the funfair has set up its stands and rides. It is among the shouts of joy and bursts of noise, that at 2:30 p.m., the first explosions dig bloody ditches in the crowd massed on the esplanade. In less than half an hour, and without the sirens having had time to sound their sinister sound, the Champ-de-Mars is nothing more than a field of Death. It is among an indescribable chaos that the first rescuers, rushed rapidly from all corners of the city, persevere on the jagged rides, lift the collapsed stands, very carefully, liberating the few survivors. It is especially children on vacation, for this special Monday, that the rescuers will line up in the 'chapelle ardente' erected in a hut on the edge of the Champ-de-Mars. The rest of the city was unfortunately not spared. The railway junction of the marshalling yard being, it seems, the target attributed to the Flying Fortresses of the US Bomber Command, the station district and the Saint- Hélier street were particularly hardly hit. At the end of Saint-Hélier street, filled with debris, the company "Economique" shows the square silhouette of its warehouses on rue Monseigneur-Duchesne. It is in the cellars of these warehouses, along the railway line, that the 71 employees perished, prisoners in their burnt shelter. Hundreds of bruised, burned and torn bodies are now piling up in the city's main hospitals. The "Hôtel-Dieu" is quickly overwhelmed by this continual influx of wounded and although this drama has suddenly surpassed in horror all what the rescuers could imagine, the help is organized very quickly. The areas which ar not hit send their teams of D.P.; volunteers methodically search (using iron rods) the rubble of collapsed houses. Hospital staff, firefighters, under the orders of Commander Dubois, the Red Cross, organize a rapid evacuation. The entire city is participating in the rescue and accommodation of its victims. In addition to the station district, the 'Cimetière de l'Est' (Eastern Cemetery), rue de Châteaugiron, and 'boulevard Villebois-Mareuil' districts on the one hand, and the streets Ange-Blaise, Ginguené, the quarter of T.S.F. (radio company) established rue de l'Alma on the other hand, are the scene of the same scenes of desolation. Only damage to German military installations, the artillery park of the Guines barracks and the Colombier barracks were hit. German and Vichy propaganda were able to make the best use of these fatal errors of Allied aviation

The bombs did not spare the funfair on the Champ-de-Mars

'Place de la Gare' (Station square), a few minutes after the end of the alert. On the right, avenue Louis-Barthou, facing the Champ-de-Mars esplanade. In the background, we can see the building of lsly street

The Janvier avenue and the railway station

The rue Saint-Hélier which was one of the districts mostly hit by the bombings throughout the war

The crossroads of St-Hélier street, on the left Laënnec boulevard, in the center, in the background the buildings of the 'Economique' and on the right L.-Decombe street

The 'Economique', Monseigneur-Duchesne street, the buildings burned, killing the 71 employees

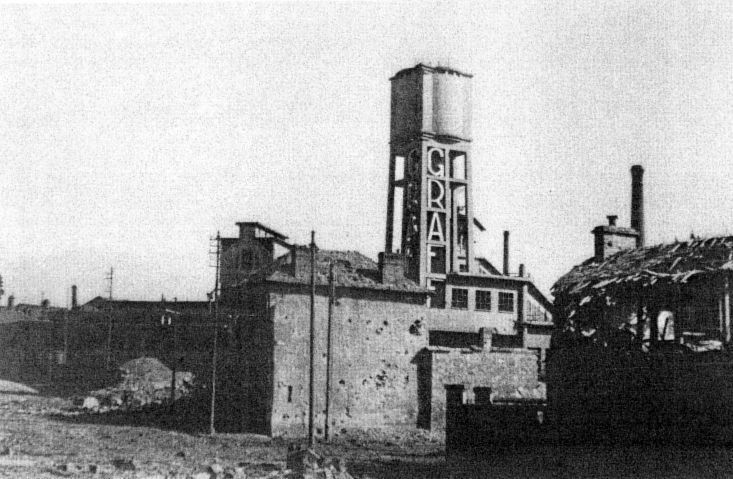

Solférino boulevard, the Simon printing house is devastated, and the Graff brewery at the corner of Pierre-Martin and St-Hélier streets has not been spared

The Berlinquin and the devastated graves

The funeral of the victims takes place on March 11. General view of the ceremony. The Minister of State, Mr. Cathala, delivers the funeral speech in the presence of the French and German authorities

St-Pierre square, at the end of the funeral service

It is the D.P. volunteers and the scouts who were entrusted with the difficult task of identification. The total number of bodies stood at over 300, many of which were never identified. Finally, Rennes had just suffered its first but very hard bombing. The suddenness of the attack, the destruction of targets of no strategic interest, the massacre of hundreds of innocent people left the hearts of Rennes with a feeling of indignant anger mixed with concern. During the two months which followed, the alerts were practically daily and the descent to the shelter became common thing for a population now realistic and disciplined.

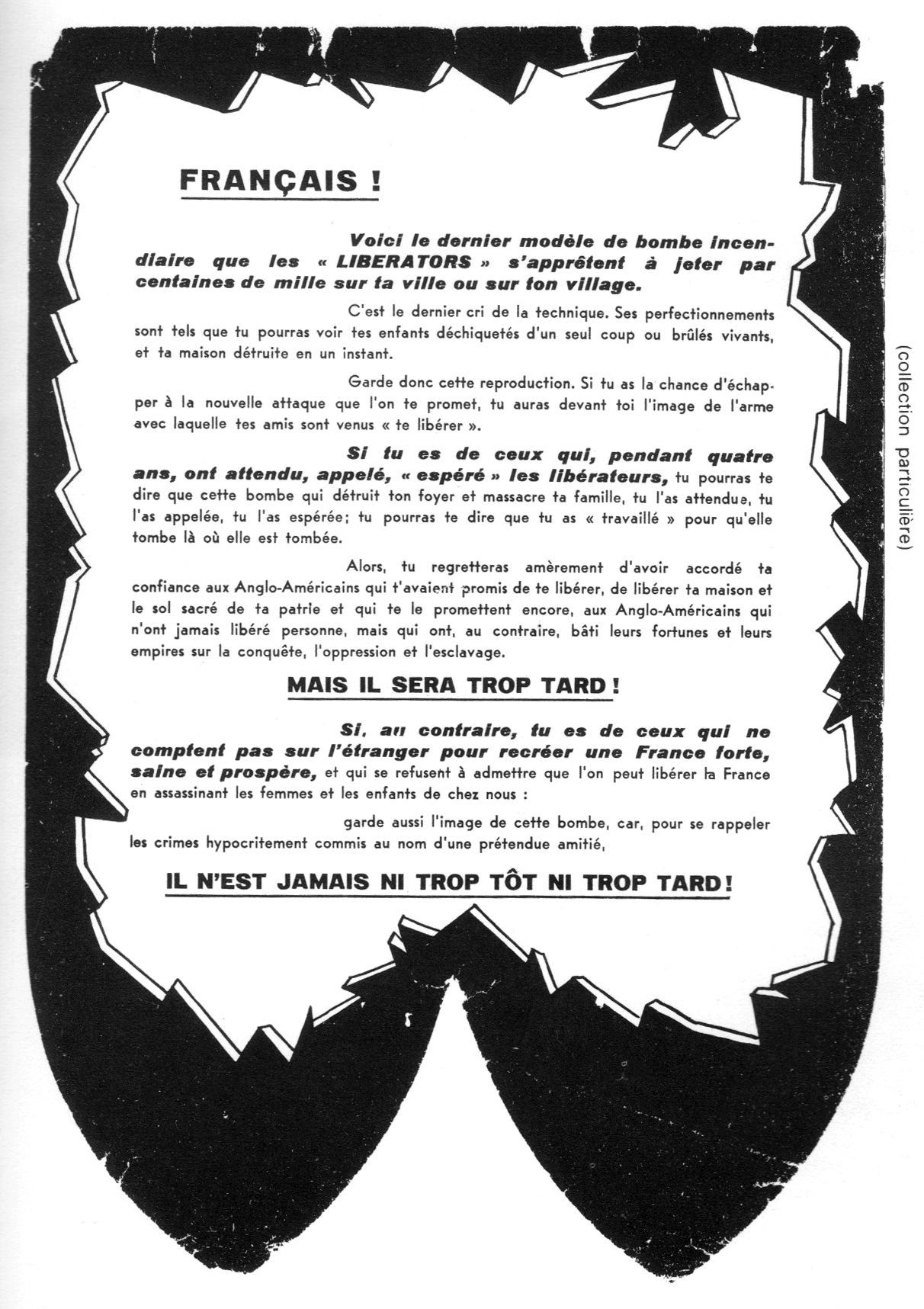

Tract distributed in Rennes following the bombing of March 8.

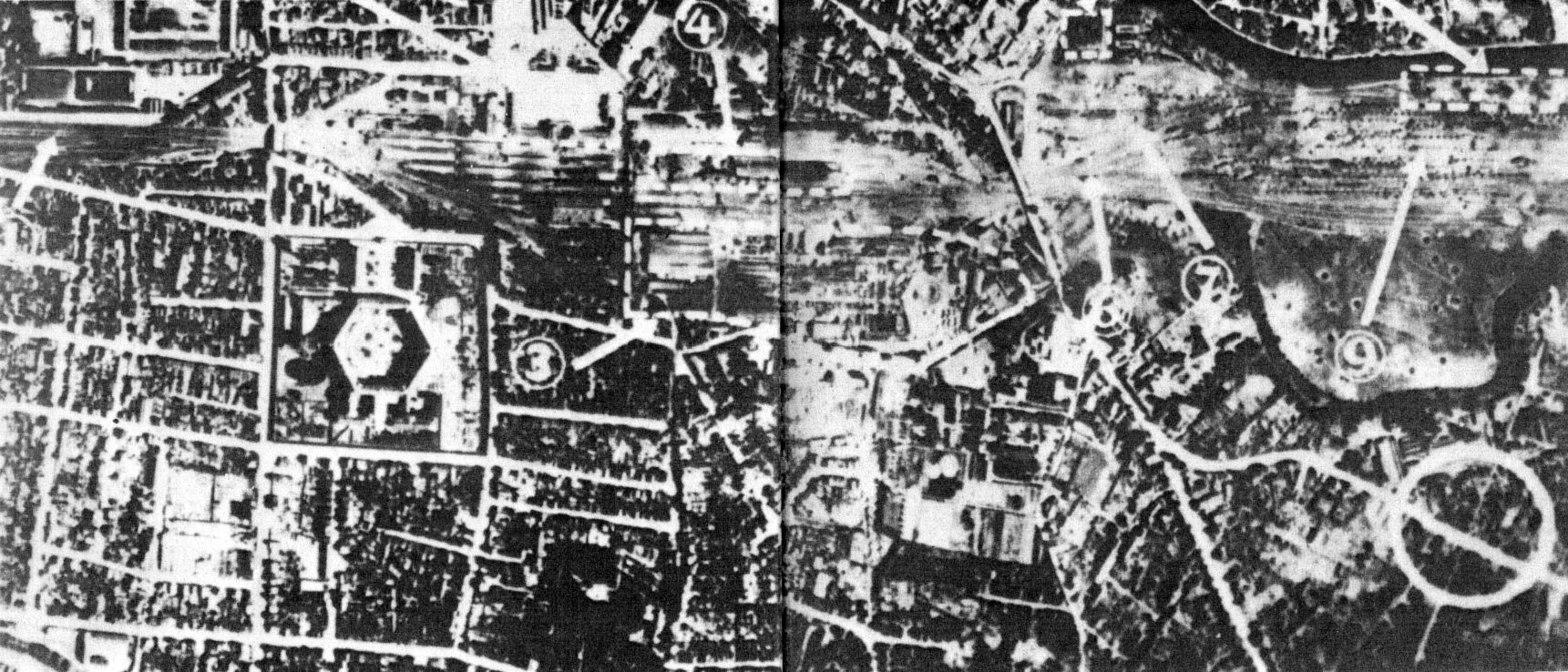

U.S.A.A.F document. showing the damage caused during the bombing of March 8, 1943

1. The tracks along the Colombier boulevard and passing under the Alma bridge.

2. The passenger station and 1 square.

3. The workshops, delimited to the north by the railway line and to the south by thr Pierre-Martin street.

4. Warehouses and the freight station.

5. The 'Economique', Mgr-Duchene street.

6. and 7 The rail nodes, the main target of the allies.

8. The warehouses of the marshalling yard.

9. Trains parked.

Rennes under occupation

Author : François Bertin

Editions Ouest France 1979

Research Vincent Sévellec - ABSA 39-45 - Septembre 2004

Rennes Eastern cemetery, monument in memory of those killed at the "L’Economique" store

Photo Daniel Dahiot (ABSA 39-45)

Ajouter un commentaire